When the pandemic has passed into history, what will be its implications for the role of the state in our economy? Some think it will (or should be) the replacement of one -ism with another. But to see the issues we face next through the prisms of an -ism could prove more of a prison than a roadmap. Ours is a mixed economy with both a sizeable state and private sector and is likely to remain that way; the question is more whether the state will be a bit bigger or a bit smaller.

In thinking about this, it is useful to think about the economic functions of the state. First it provides some services directly: defence, justice, compulsory education and healthcare. These services are publicly-provided in all high-income countries, however ‘free market’ their ideology, because there would be serious failures if they were not. However, there is variation in the quality of provision of these public services and Covid has exposed some of that. We have become aware that a pandemic risks overwhelming our healthcare systems so that we need to build more resilience into it in normal times. So expect to see more money spent on healthcare.

The shockingly high death toll in our care homes should be an impetus to a radical re-think in social care. While many working in the sector have done their best, as the pandemic has made clear, overall it is under-resourced and much more amateurish than other caring professions. The low level of pay and poor working conditions of care workers relative to other jobs is a national scandal. Despite everyone recognising the problem, it has got worse in the past decade. Hopefully, Covid will provide the necessary impetus for change. I think we need to face up to the fact that most of care has to be publicly-provided and paid for by the state, and plan accordingly.

As well as providing public services directly, the state also takes money from some people and gives it to others. There are two aspects to this: social insurance and redistribution. The state provides insurance for us to have an income if we are unlucky enough to lose our job or become too sick to work. In recent decades, the private sector has shifted some risks away from itself, leaving the state as the effective ‘insurer of last resort’ when the good times end. This was a feature of the financial crisis, but the pandemic has exposed other aspects of this. Taxes are lower on the self-employed because they were supposedly entitled to less support when not working; this tax advantage is one reason for the rise in self-employment. Sick pay is low, so that workers who are ill may be tempted to go to work, risking that they infect others. Without an adequate insurance mechanism in place before the crisis hit, we have had to invent one quickly. But much better to have a resilient social insurance system. Again, this would mean a bigger state.

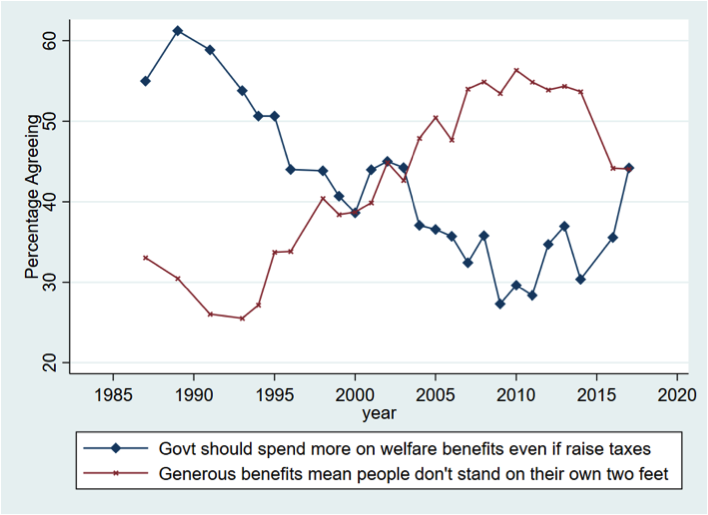

Not everyone faces the same chance of needing social insurance. Some people are more likely to be without work than others, some healthier than others. So, social insurance systems also redistribute in a systematic way from some groups of people to others. If the people paying for the system think that this is a system they are unlikely to need, and that those who do are in some way ‘undeserving’, this is likely to lead to a low level of social insurance. Figure 1 shows that support for more generous welfare benefits fell from the 1980s to 2010 while the fraction believing benefits prevent people from standing on their own feet rose.

Figure 1. Support for welfare benefits

Source: British Social Attitudes

Since 2010 attitudes have been becoming more favourable to the welfare state and the pandemic may accentuate this trend. Covid is a wake-up call to many that social insurance systems are something they might sometimes need and that they need to be at a level that is fit for purpose. This would again suggest a bigger role for the state in the future. Against this is the argument that things like the furlough schemes may be seen as one-offs for an extreme crisis and one can revert to business as usual once it has passed. Though unwinding the furlough scheme may be much harder than setting it up (see this note on the difficulties of doing this).

So there are arguments that the economic role of the state may be more important in the future than it has been in the past. But if public expenditure is a higher share of national income, taxes will also need to be and a way has to be found to do that and it will not be easy. There have been protests in the past about changes to tax rates for the self-employed, or to property and inheritance taxes – and are likely to be again even if changes are needed. Underlying this reluctance may be the view that the government is not very competent, that it cannot be trusted to use resources wisely.

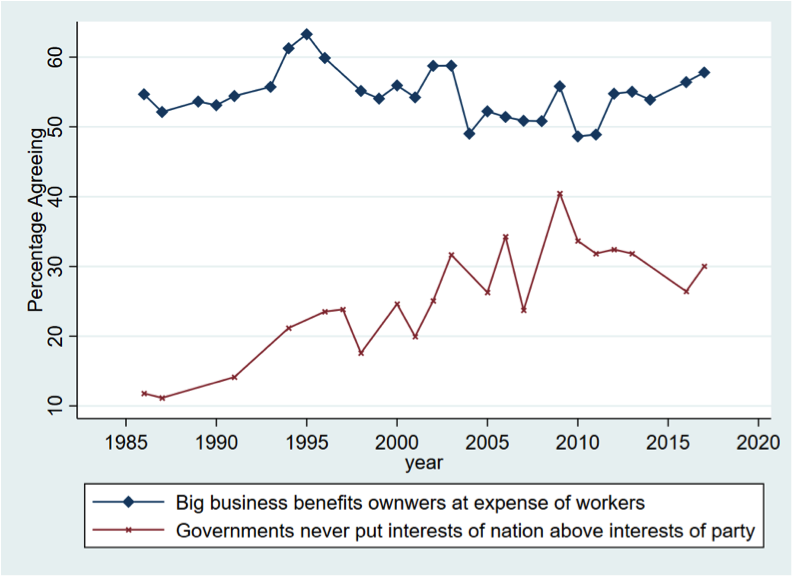

Figure 2 shows that trust in government to do the right thing has fallen over time, while confidence in business does not show the same trend.

Figure 2. Trust in business and government

Source: British Social Attitudes

It is this growing lack of trust that could stem those arguments for a larger state.

We have spent the last few weeks clapping on our doorsteps at 8pm every Thursday, volunteering in our hundreds of thousands and donating to Captain Tom Moore’s 100th birthday appeal. It is clear the public wants to recognise the phenomenal work of those public-sector workers on the frontline – and support those low-paid, precariously-employed workers who are now deemed essential.

But, as the UK heads towards one of the highest death rates from Covid-19 in the world – the question is whether we will trust this government, or any government, to do that.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by dimitrisvetsikas1969, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Alan Manning is professor of economics at LSE’s department of economics and director of the community programme at the Centre for Economic Performance. His research generally covers labour markets, with a focus on imperfect competition (monopsony), minimum wages, job polarisation, immigration, and gender. On immigration, his interests expand beyond the economy to issues such as social housing, minority groups, and identity. Alan holds a DPhil in Economics from Oxford University. For more on his work, visit his personal website.

Alan Manning is professor of economics at LSE’s department of economics and director of the community programme at the Centre for Economic Performance. His research generally covers labour markets, with a focus on imperfect competition (monopsony), minimum wages, job polarisation, immigration, and gender. On immigration, his interests expand beyond the economy to issues such as social housing, minority groups, and identity. Alan holds a DPhil in Economics from Oxford University. For more on his work, visit his personal website.