Opening offices will be our decision. When and if our employees come back, will be theirs.

— Jennifer Christie, vice president of people at Twitter on the company’s blog

Large swathes of the economy seem to have painlessly switched to working “digitally”. Zoom, Cisco Webex and Microsoft Teams have kept most of us working in the “knowledge economy” fully employed. Was all that commuting and getting dressed really necessary? Perhaps time to get rid of offices entirely?

Many people have been working in teams that were at varying degrees “virtual” for decades and have had very mixed experiences. Working in a global virtual team can be particularly challenging if you have never met your colleagues and never learned to really understand what they mean in their electronic or telephonic communication. One project I was involved in was completely stuck for months because of inability of the London and Tokyo offices to agree. The London people were experienced and hardworking, as were the Japanese team, but something was not quite working. Both sides could communicate in English, even with a challenging variety of accents. All it took to resolve the issue was a one-week trip to Tokyo that involved a great deal of drawing on paper, waving hands around and eating yakitori. The fundamental problem had been London not listening to the message that was buried in all the communication and conference calls about how the Japanese market worked. Once there was a common understanding, everyone worked hard together to move in the same direction.

Generally, though, one business trip is not enough to resolve the problems of a “team” that is distributed across the globe. In another role, I found it very hard to establish a trusting working relationship between on-shore and off-shore portions of what was supposedly the same team. It was only while sitting in the offshore office, listening to a “town hall” where the senior management explained that their objective was to take over as much work as possible from the on-shore team, as opposed to do the best possible job, that I realised the trust issue was simply down to different parts of the virtual team working to very different incentives.

Communication in any organisation does not solely rely on formal channels or hierarchies. The large formal conference call, with everyone conscious of the need to not say anything embarrassing or against the official line, can be a terrible way to understand what is really going on. Official communications can be as much about control as sharing information. The famous and seemingly random water cooler or kitchen conversations are only the tip of the iceberg of informal communications networks. I have found smokers and coffee connoisseurs two of the most useful sources of information because there is always a time when you can get hold of them for an informal chat. Coffee lovers always insist on leaving the building to find “decent coffee”, which provides a great opportunity to tag along. Smokers can also be predictably easy to get hold of and surprisingly frank if found on the right street corner. I will always remember the freezing cold street corner where I was dragged by a member of a project team, to listen to a former team member explain to me, in between puffs, why the previous attempt at a project had been a complete failure.

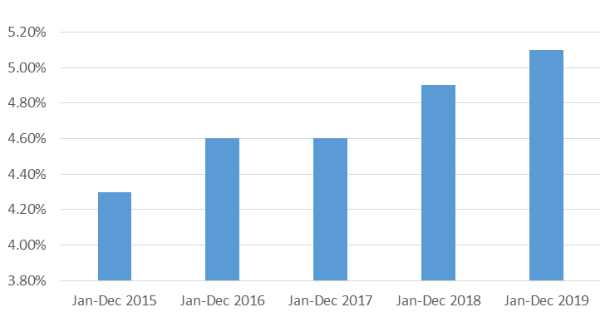

Though some degree of home working or working in virtual team has been common, until Covid-19 it was still a minority activity. In many developed countries, only a small percentage worked mostly from home. For example, just over 5% in the United Kingdom in 2019. Similar trends were shown in other countries until the lockdowns. Suddenly everyone who could work from home was made to work from home. Before jumping to conclusions about the future of work based on the apparent success of home working recently, it is worth considering what evidence we have about home working particularly about the effectiveness of “virtual teams”.

Figure 1. Percentage of people in employment who mainly work in their own home, UK

Source: Office of National Statistics

There is always the danger in the world of management decision-making that an idea gains widespread acceptance not because of supporting evidence but because of the enthusiastic promotion by “gurus” and those who profit from selling the next big thing. To encourage a little more rational thought before fundamental changes are made to the nature of working, the Center for Evidence Based Management (CEBMa) in co-operation with the Central Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) has undertaken a review of the existing scientific evidence on the effectiveness of virtual teams.

Rather than cherry pick specific research papers to fit pre-conceived views, CEBMa and the CIPD performed a rapid evidence assessment (REA). This identified over 350 papers on the topic of virtual teams. Of these, 29 primary studies and nine meta-analysis were found to be of sufficient quality/relevance to provide meaningful insights into the value and challenges of virtual teams.

The first challenges in trying to understand the effectiveness of virtual team results are related to definition. There is a very wide variety of definitions in the scientific literature which we reduce to a common denominator of two or more persons in different locations, working collaboratively to achieve a common objective, predominantly using electronic media. The second was that (at least pre-Covid) there are degrees of “virtuality”, varying from an entirely distributed team to teams that are to varying degrees distributed either in terms of number of staff or by the amount of time spent away from a central workplace.

Even adjusting for these challenges some key findings emerged

- Team virtuality moderates team effectiveness — the more virtual a team, generally the less effective it is.

- Computer-mediated communication is negatively related to team effectiveness – generally the less face-to-face communication, the less effective a team.

- Physical dispersion and asynchronicity is negatively related to team effectiveness – the more dispersed virtual teams both geographically and across time zones, the less effective they are. Working in same space and during the same time of day is generally more effective.

- Factors known to enhance team effectiveness are even more important for virtual teams – it is even more important for a virtual team to have high levels of trust, social cohesion, information sharing and effective transactive memory systems (TMS). TMS refers to a form of knowledge that is embedded in a team’s collective memory. This collective memory works like an indexing system that tells members who knows what.

There are some methods to partially mitigate the problems. Media richness e.g. increased video conferencing (with the video turned on) can reduce the negative impact of virtual teams. Training teams specifically in team working can help, as can team-building exercise, particularly when a virtual team is first created. Negative impact is also likely to be lower if a virtual team is carrying out certain types of work. Notably if the work is repeatable, easy to measure and can be carried out autonomously with little team interaction.

Overall the findings of our assessment provide a strong warning to managers and organisations: Compared to face-to-face teams, virtual teams tend to display lower levels of intra-team trust, social cohesion, communication, consensus, information sharing, and tend to have less developed transactional memory systems. As a result, virtual teams are generally less effective than face-to-face teams. Though additional efforts can be made (and costs incurred) to counteract these negatives, organisations need to think very hard before radical long term shifts towards making teams more virtual.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- Author’s disclaimer: “The opinions are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of the “Center for Evidence Based Management”.

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Andrea Piacquadio, free, via Pexels

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Martin Walker is director of banking and finance at the Center for Evidence-Based Management. He is the author of the book Front-to-Back: Designing and Changing Trade Processing Infrastructure and contributed to the book Evidence-Based Management: How to Use Evidence to Make Better Organizational Decisions. He has also published several papers on banking technology. Previous roles include global head of securities finance IT at Dresdner Kleinwort and global head of prime brokerage technology at RBS Markets. He has been asked to provide evidence to two parliamentary inquiries, “Digital Currencies” and “IT Failures in the Financial Services Sector”. He received his master’s degree in computing science from Imperial College, London and his bachelor’s degree in economics from LSE.

Martin Walker is director of banking and finance at the Center for Evidence-Based Management. He is the author of the book Front-to-Back: Designing and Changing Trade Processing Infrastructure and contributed to the book Evidence-Based Management: How to Use Evidence to Make Better Organizational Decisions. He has also published several papers on banking technology. Previous roles include global head of securities finance IT at Dresdner Kleinwort and global head of prime brokerage technology at RBS Markets. He has been asked to provide evidence to two parliamentary inquiries, “Digital Currencies” and “IT Failures in the Financial Services Sector”. He received his master’s degree in computing science from Imperial College, London and his bachelor’s degree in economics from LSE.

Classic Chester Bernard; all formal organisations have embedded within them normal networks; it is the latter that determines the former’s efficiency, effectiveness and competitive advantage. Back in the day, I counted lots of unwashed coffee cups.

Bernard should be spelled Barnard; normal should read ‘informal’; – too fast with the typing, sorry about that.

While this article shares some good effectiveness tips and practices, I and most actual research and mass employee surveys disagree with this author’s conclusions, and not just because I am an advocate for virtual work. Self-reports are especially powerful in indicating dramatic productivity increases.

Right now during the COVID-19 crisis, however, productivity is suffering for many reasons, mostly that 42% of US workers are leading or working in a virtual team for the first time, overnight with no training or prep, while experiencing tremendous anxiety overall.

I encourage readers of this article to look at the bigger picture and other drivers for a blended, flexible workplace.

Hi Trina,

I can see that you have a great deal of experience in promoting virtual teams but as stated above the findings were based on analysis of 29 primary studies and nine meta-analysis.What research specifically contradicts it other than your experience? Also why do you think self-reports of productivity can be relied on?

Thanks for reading.

Martin