During sudden onset crises, such as pandemics, military conflicts, hurricanes and large scale bushfires, the number of unusual, complex business problems surges dramatically, and managers at all levels of an organisation’s hierarchy need to be able to deal with them. However, because of the erratic occurrence and unique structure of these problems, managers are not often trained in how to solve them. Examples of such problems are: When national borders are closed, how do we deliver our products to our customers?; Can we replace analogue products with digital services?; When the value of a local currency has dropped dramatically, how should we price our products?; How can we support employees located in risky areas?

Seventy-five per cent of business problems do not get solved

Confronted with such a problem, the manager responsible needs to act fast to find a solution. However, on average, 75 per cent of these problems do not get solved satisfactorily and as a result, the process of finding a solution has to start all over again. Here we recommend the best way for a manager to navigate choices about who to solicit help from when creating a solution that is both effective and original. To generate these recommendations, we asked 120 managers working in large international companies who they collaborated with when solving unusual business problems.

Use your geographically distant colleagues

The crucial activity when solving an unusual problem is to gather new knowledge in the form of information, facts, experience and know-how. Such knowledge usually exists in the heads of other individuals who are widely scattered across the organisation. Who should you—as the manager responsible for solving the problem—ask?

First, do not waste your own or others’ precious time and energy contacting colleagues who do not have new knowledge available. Novelty in knowledge is essential when you are striving to create a solution that is original. Set up a virtual meeting with a colleague in a different geographical context. Even though virtual communication can hamper interactive discussion aimed at uncovering new knowledge, the potential gain is worth the time and effort. A colleague who works in a different geographical location (let’s say, in a country that has experienced a health crisis) may have dealt with a similar problem or situation before.

Search for directly applicable knowledge

Second, avoid asking colleagues who share knowledge that is interesting but not applicable. Colleagues often mean well but can overload you with exciting and creative ideas. But if you are pressured to solve the problem and you don’t have the time to filter and fully grasp the knowledge provided, which in itself may be wrong or misleading, this can lead to a delay in developing a solution or in the problem not being solved at all. To avoid this, you should make smart choices based on the types of answer you hope to receive.

Decide in advance whether it is innovative ideas or expertise that you are looking for

The difference between these two should be reflected in the precise nature of the questions you ask. Questions aimed at eliciting innovative ideas in the form of creative, unstructured or even off-the-wall responses might be:

- What is this all about, what is happening here, any suggestions?

- Let’s think outside the box, what solutions can you think of?

- Maybe the problem is about something else, have we uncovered all the causes?

- We don’t have any financial resources available to implement the solution, what do we need to improvise?

- …

Expertise, in contrast, fills clearly defined knowledge gaps, and questions should be ones such as:

- Do we have any previous experience as to the impact this problem will have on our sales figures?

- What local regulations do we need to take into account?

- Does the solution comply with corporate strategy?

- Can we just change the size of the packaging?

- …

Differentiate between business functions

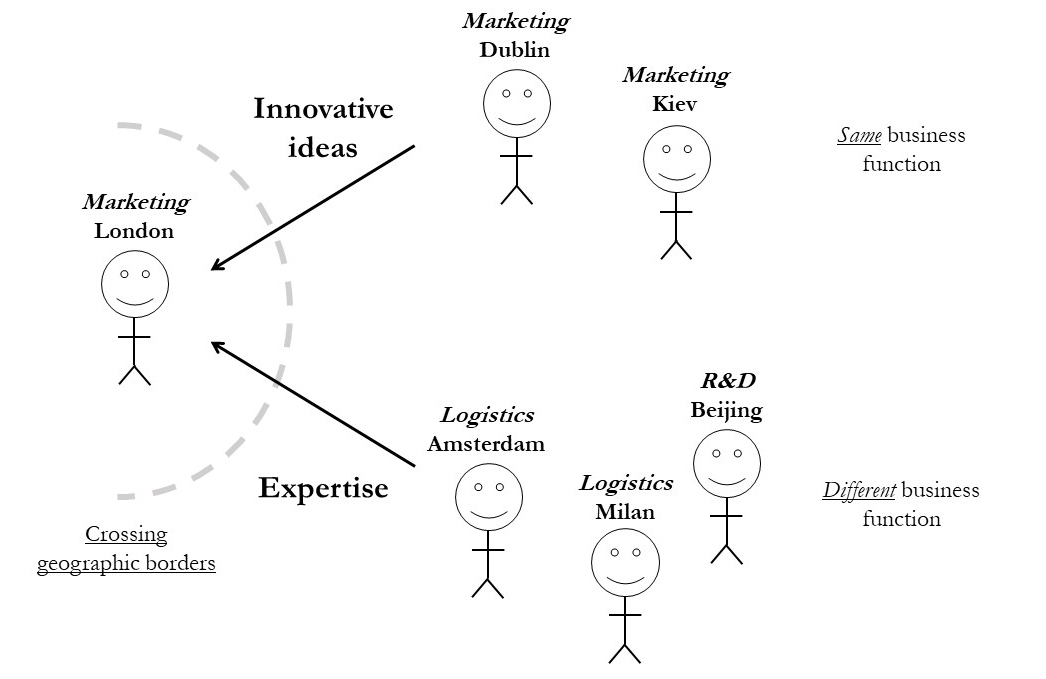

To find a colleague with the right answer, we recommend differentiating along business functions such as R&D, strategic services, manufacturing, marketing, sales, logistics, or back office (see Figure 1).

When gathering innovative ideas, choose someone from the same business function: Being affiliated to the same business function means a common professional specialisation. You share similar values, background knowledge and ways of doing things. This makes it possible to engage quickly in an in-depth discussion aimed at uncovering innovative ideas that are directly applicable.

When gathering expertise, choose someone from a different business function: While it is difficult to quickly grasp innovative ideas across functions, this type of collaboration encourages the contribution of expertise which aims to tackle clearly defined knowledge gaps. It is important to ask questions that aim at these gaps.

Figure 1. Create an effective and original solution to an unusual business problem

Teamwork: Sometimes you will want to connect with more than one colleague. Several recommendations are relevant in this instance. Knowing who can contribute what enables you to make smart decision when assembling your team.

Make smart decisions

We suggest that managers undertake two actions:

Make use of a digital communication tool to foster discussion with both familiar and unfamiliar colleagues. In this way, you can create an original solution and form new relationships.

Second, before setting up a meeting, think carefully about what kind of answer you expect to receive. If you are looking for innovative ideas, ask colleagues with the same functional backgrounds. If you are looking for concrete expertise, engage with colleagues from a different functional background. In doing so, you can create an effective solution.

These problem solving recommendations are valid for every manager who needs to create a solution that is both effective and original.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Accessing diverse knowledge for problem solving in the MNC: A network mobilization perspective, Global Strategy Journal.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image via pxfuel, Royalty free

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Renate Kratochvil is a postdoctoral researcher at the BI Norwegian Business School, Oslo. She investigates how managers can improve their skills in solving problems, capturing opportunities and thinking strategically with the help of new digital technologies.

Esther Tippmann is a professor at the National University Ireland, Galway. She is an expert in problem solving and entrepreneurial action in multinational corporations.

Esther Tippmann is a professor at the National University Ireland, Galway. She is an expert in problem solving and entrepreneurial action in multinational corporations.

Andrew Parker is a professor at the University of Exeter, United Kingdom. He is an expert in social networks analysis and creative solution development.

Andrew Parker is a professor at the University of Exeter, United Kingdom. He is an expert in social networks analysis and creative solution development.