By the beginning of 2020 women’s labour force participation stood at 58%, nearly a three-fold increase in the past century (civilian labour force participation rate, 16 years and over). By September 2020, in the wake of Covid, this share had fallen by over two percentage points. This statistic masks a potentially huge emerging gender gap: According to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, four times more women than men dropped out of the labour force in September 2020.

Three steps can be taken to reduce the burden on working women during the Covid recovery. First, implement changes to maternity leave and pension regulation to eliminate the different treatment of women than men. Second, vocational training programs in other G7 countries yield important lessons for how to re-include women in the labour force once they managed to update their skills. Finally, the crisis has laid bare the actual gender gap in pay and hours worked once household work is taken into account. Documenting these differences may bring about a productive discussion about the ways that public policy can be redesigned to better integrate women.

The Covid crisis hurts women disproportionately

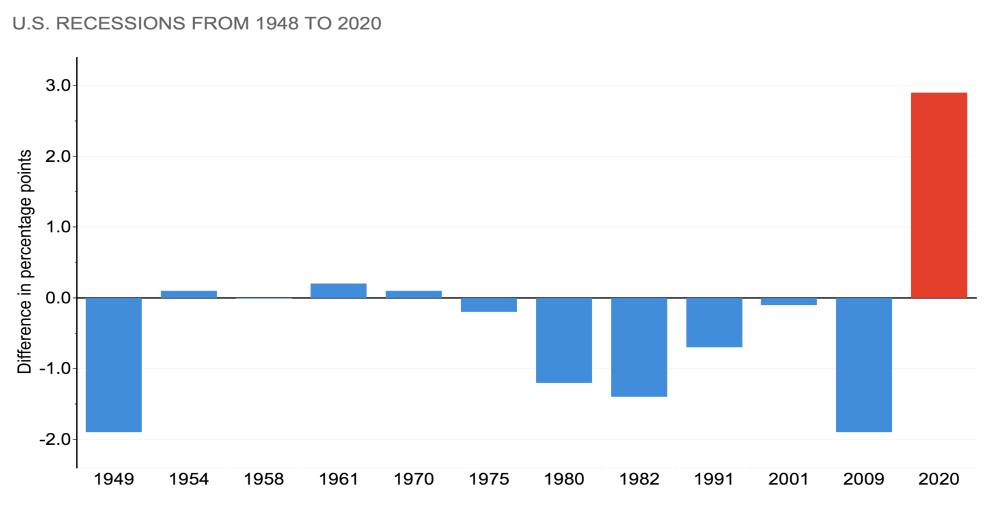

The COVID crisis is different from every previous economic crisis in the United States since World War II, when men lost proportionately more jobs. In particular, women have lost nearly three percentage points more jobs to unemployment than men (figure 1).

Figure 1. Difference between rise in women’s and men’s unemployment

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. EconoFact.

The larger impact of COVID-19 on women’s versus men’s employment is also observed in other G7 countries including Canada and the United Kingdom. In these countries, the sectoral distribution of women’s employment together with the increase in childcare and household needs accounts for a larger impact of the pandemic on women’s than men’s employment.

First, the increasing gender gap is explained by the disproportionate impact COVID had on jobs and occupations that tend to employ more women. Many women work in sectors such as restaurants, tourism and office space maintenance, which were severely affected by the crisis. US employment losses through September were the largest in occupations requiring personal contact (e.g., retail), where women account for nearly three-quarters of employment.

Second, previous studies on the US labour markets show that working mothers were already shouldering the majority of family caregiving responsibilities. The disruptions to daycare centres, schools, and after-school programs have been hard on all members of the family, but the empirical evidence since the Covid crisis started shows that working mothers are more frequently reducing their hours or leaving their jobs entirely in response.

In particular, studies show that women have absorbed over two-thirds of the additional responsibilities due to COVID. The increase in childcare needs affects women more than men for several reasons. There are many more single mothers than single fathers: 21 per cent of children in the US lived with a mother with no partner present in 2017, while 5 per cent of children lived with a lone father. Among married households, mothers provide more than 60 per cent of total childcare. Women provide the majority of childcare even in couples where both parents work full time. As a result, women have picked up the majority of the increased childcare needs during the crisis. Among parents working from home during the crisis, fathers have increased their time spent on childcare and home schooling by 4.7 hours per day, versus 6.1 hours for women.

The US economy will eventually bring back jobs in those industries that employ women. One example of such an industry is healthcare, where women take nearly 80 per cent of the jobs. This uptake will, however, take time to develop and it will require new skills, which implies programs for vocational training. In this regard, the United States can learn from other G7 countries that have developed extensive vocational training and retraining programs. Previous research has analysed the main features of such training programs in France and Germany.

Three areas of analysis

Three distinct areas of work will help alleviate the burden on working mothers. First, legal changes, including to federal and state-level regulation, to improve the environment for the employment of women. A particular focus is needed on maternity leave legislation and pension rules, both of which at present significantly disadvantage women in the United States relative to their peers in other G7 countries. Such legal change has already taken place at the state level – both California and New York implemented new mandated maternity leave regulation for public employees in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

Second, the establishment of vocational training financing schemes with a particular focus on women is sorely needed. Such schemes exist in every other G7 country, prioritising certain sectors that are particularly affected by Covid. This policy implies extensive analysis on the effects of Covid across sectors, beyond the initial emergency response. Third, there should be measurement of the effects of the Covid crisis on the responsibilities within the household. Previous studies show a disproportionate burden on women, especially in lower socioeconomic groups. Analysing in detail the additional unpaid work that women tender in the household gives a benchmark of the actual gender gap in hours worked and pay. In this regard research in the United States lags research in other G7 economies like Canada and the United Kingdom, where measures of the actual gender gap more than double in terms of pay.

There are several other implications from the Covid pandemic on the well-being of women. The most important one is violence against women at home. Anecdotal evidence suggests the incidences of such violence have increased during the crisis. A second concern is the rising income inequality from women falling out of the labour force, and the implied social dimensions of this exclusion.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Daniel_Nebreda, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at LSE and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank. He is the founder of the World Bank’s Doing Business project. He is author of Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account (2014) and principal author of the World Development Report 2002. He is also co-editor of The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism (2014).

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at LSE and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank. He is the founder of the World Bank’s Doing Business project. He is author of Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account (2014) and principal author of the World Development Report 2002. He is also co-editor of The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism (2014).