By all accounts, trust in the corporate sector is at an all-time low, and perhaps – for the first time in the history of humankind – it is a global phenomenon. While stock markets worldwide, and particularly in the United States, continue to rally, this is accompanied by an unprecedented economic contraction, conservatively estimated at 5 to 10% of global GDP, alongside steep and growing unemployment.

Strong stock market performance, underpinning political outcomes in many countries, is a myth perpetuated by stellar performance of – predominantly US – technology stocks, led by Apple, the highest capitalised company in the world. Indeed, Apple and its high-tech peers are not only dominating market indices and portfolios of institutional investors but are also setting the terms of future of global economic governance.

While these companies, dubbed by the analyst community as “high value” stocks, did not perform strongly during the last financial crisis, they are virtually the only reason stock markets are up, at least in the US, where most are listed. Driven by a spike in retail investor speculation, this has implications not only for shareholders, but also for governments wondering how to protect this new breed of “tech crown jewels”.

In previous crises, policymakers have been primarily preoccupied with protecting legacy national champions such as airlines and automobile manufacturers. This time, in addition to investment restrictions, they are also relaxing rules on poison pills (a defence strategy used by target firms to prevent or discourage a potential hostile takeover) and even introducing golden shares (a nominal share that outvotes all others in specified circumstances, often held by governments). Yet, that is only part of the answer, as is rests on an outdated concept of what is economically strategic.

The corporates that governments should worry about protecting today are not only legacy national champions, but also – or perhaps especially – innovative start-ups. These companies are the kernels of future global tech giants whose role is expanding. Large tech firms flex their muscles by holding negotiations with states (tax debate between Facebook and France), controlling speech (Twitter’s role in American elections) and supporting social movements (Facebook’s role in Egypt’s revolution).

While before the onset of the virus, governments and international organisations (notably the European Commission) showed concern about growing economic concentration – with discussions about potential breakup of Facebook, for example – this conversation has been muted in 2020. Indeed, with consolidation in traditional sectors and acquisition in the tech sector, the opposite tendency can be observed.

Multinational enterprises’ dominance in the world economy is set to be bolstered by an important trend that continues unabated: the acquisition of emerging market start-ups by their larger, international rivals. In many emerging economies, new incumbents that disrupted traditional industries have subsequently been acquired by their established, cash-rich rivals. This is occurring even in liquidity abundant regions such as the Middle East.

In Dubai, for example, Careem, which disrupted the local car transport sector in 2012, previously dominated by state-owned Dubai Taxi, was acquired by Uber earlier this year. Likewise, Souq.com, launched in 2005 with investment by the Saudi sovereign wealth fund and prominent private Emirati investors, was acquired by Amazon in 2017. Even during the pandemic this trend continues unabated: a few weeks ago, Emirati Instashop was acquired by German Delivery Hero.

The same trend is also occurring, and even at a faster pace, in less wealthy regions of the world, where international conglomerates swallow their local competitors. This scenario has already played out on several occasions, for example with the acquisition of India’s online retailer Flipcard by American Walmart in 2018, in a deal that galvanised attention in the country.

This acquisition spree is primarily led by Chinese and American conglomerates, most active in emerging markets. This will pour further oil in the fire of economic warfare between the United States and China, witnessed in the recent Tik Tok case and in the introduction of restrictions on listing of “foreign” (read Chinese) companies by American exchanges.

US and Chinese tech conglomerates are vying for control of the most lucrative sectors in the long term, notably e-commerce. As the COVID pandemic is decimating traditional retail, e-commerce is becoming the only “safe” marketplace. No wonder Amazon’s share price has surged 70% during the pandemic and it is one of few multinationals increasing staff globally. Its recent fake product reviews scandal highlights what is at stake.

While in the past, governments have tried to create a “protective environment” for airlines, natural resource and utility companies, policymakers have now understood that most of these will be a burden on their purse for years to come. On the other hand, tax revenues from tech companies, will be a source of significant revenue for decades. Tech companies specialising on distribution of goods and services are at the pinnacle of the pyramid.

It is thus no surprise that for years now the OECD has been working to create a flat global tax on tech firms, to avoid them exploring overtures made by governments to domicile their headquarters in low tax jurisdictions. The Franco-American economic war was the most evident reason for the OECD to run to put out this fire but far from the only one. Yet fires have popped up in other locations.

During the COVID lockdown, the French government has blocked Amazon’s deliveries in France, allegedly on safety grounds, while local competitors continued their services. Donald Trump’s effort to force the sale of TikTok activity in the US to Walmart and Oracle goes further, setting a dangerous precedent which goes far beyond investment protectionism.

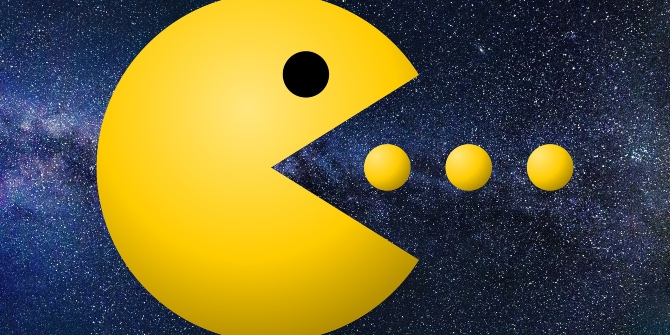

The result of these developments is an increasing concentration in the global economy, where multinational corporations, especially US and Chinese tech firms, will continue playing a game of Pac-Man. As the governance of these firms remains dominated by warring US and Chinese political and economic interests, this threatens the economic stability of an already fragile world order.

Deploying aggressive acquisition strategies, increasingly powerful US and Chinese tech firms may in the future dominate not only markets, but also nation states. If policymakers do not focus on protecting local start-ups, the centre of domestic innovation, but also citizen data will shift beyond their borders. If so, fostering national champions and protecting economic sovereignty may become an impossible task.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by p2722754, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy