Financial crises are an endemic feature of market economies. The negative effects of these crises on national economies have generally been severe, leading to banking collapses, recessions and marked increases in government debt levels (Reinhart and Rogoff, 2009). Invariably this leads governments to intervene in one way or another either to ease the damage that the crises may impose upon middle-class voters (Chwieroth and Walter, 2019) or to respond to the anti-finance sentiment emerging in the society by increasing the regulations to a socially-desired level (Dagher, 2018). Alternatively, politicians may take advantage of the prevailing interventionist sentiment in the aftermath of financial crises and introduce new policies that will favour the preferences of the financial industry at the expense of society.

In a recent paper (Saka, Ji and De Grauwe, 2020), we trace the roots of these policy interventions back to policymakers’ incentives by exploiting the variation in political accountability across a large set of countries over four decades. We first motivate our analysis with a simple theoretical set-up and then provide plenty of empirical evidence to argue that policymakers take into account both public and private interests as they undertake policy interventions after financial crises.

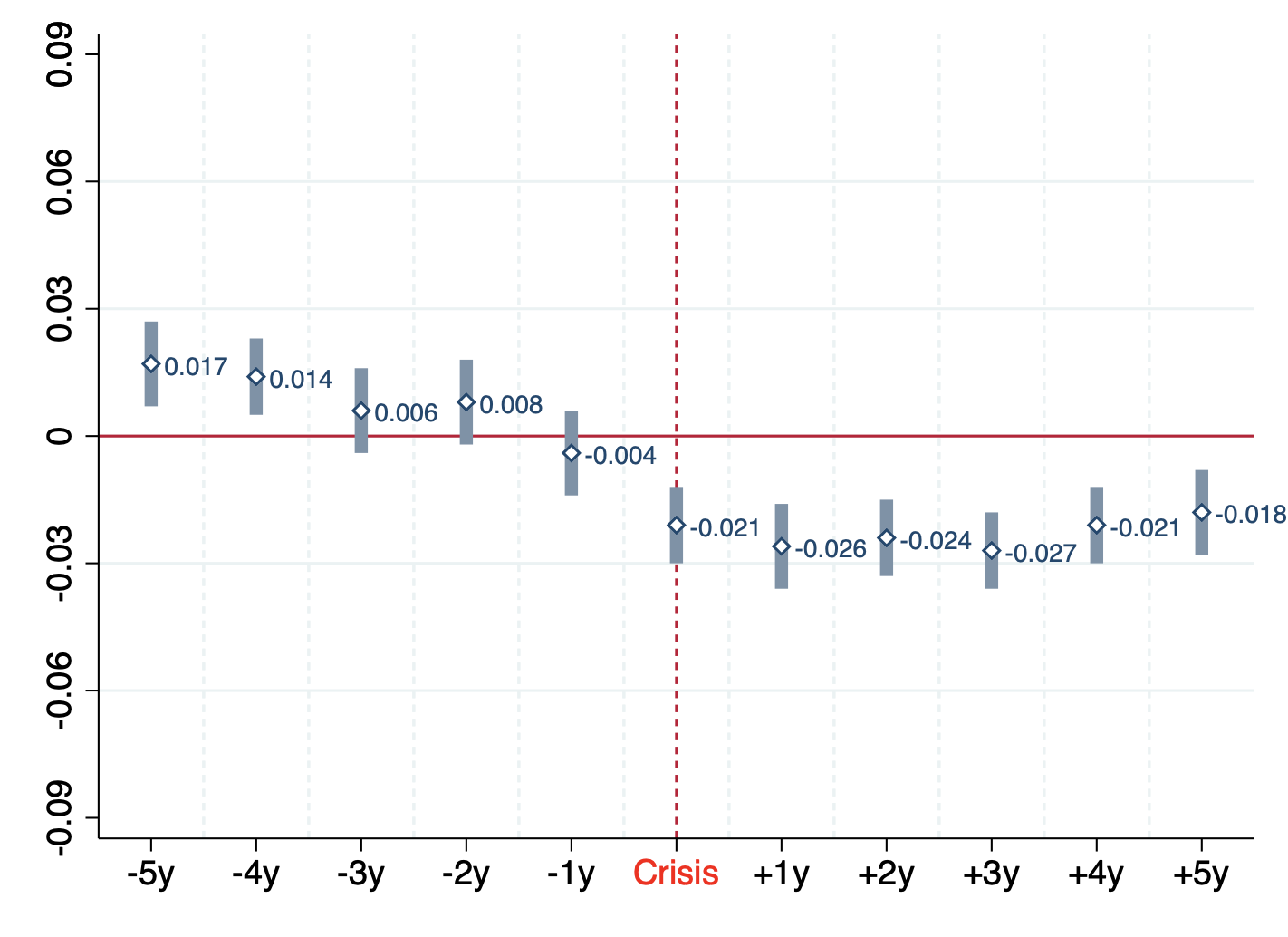

Based on a newly-merged panel of 94 countries over the period from 1973 to 2015, we employ a quasi-difference-in-differences methodology and compare the level of financial liberalisation between the two periods immediately before and after a financial crisis. This helps us capture the causal impact of a financial crisis on actual government policies across seven different financial domains and show that financial crises in general trigger a process of re-regulation in financial markets. Figure 1 plots the estimates for the effect of a crisis on the degree of financial liberalisation (vertical axis). It can be seen that immediately after the crisis financial liberalisation declines, i.e. governments tend to re-regulate financial markets.

Figure 1. Timeline for the effect of a crisis year on average financial liberalisation

Notes and Sources: The figure plots the estimates for β𝞃 from the rolling specification in Equation 3 in Saka et al. (2020). A reform database is obtained by merging two subsets of observations from Abiad et al. (2010) and Denk & Gomes (2017). Data on financial crises is obtained from Laeven & Valencia (2018). Robust standard errors are clustered at the country level and confidence intervals are at 90% significance level.

Next we compare the differences in post-crisis policymaking between democratic and autocratic settings, conjecturing that democracies are more likely to reflect public preferences due to higher political accountability on the part of policymakers. Indeed, we find that re-regulation after financial crises are only common in democratic settings (as opposed to autocracies), which — also in line with our theoretical prediction — points to a public interest channel mainly due to increased accountability of the politicians in democratic settings. This finding echoes the earlier argument that policymakers in democracies have to respond to middle-class concerns on financial stability in order to avoid the punishment in the upcoming elections (Chwieroth and Walter, 2019) and constitutes evidence that post-crisis policymaking, at least to some extent, is driven by the public interest.

In order to trace the private interest channel, we benefit from a technical aspect of the election process in democratic countries and use it as a plausibly exogenous setting that increases the possibility that policymakers become less responsive to public concerns and behave more in line with their own private incentives. Our identifying assumption here is that the incumbent policymakers feel politically less accountable and thus put more weight on their private interests when they face a term-limit. Empirically, we compare democratic leaders’ policy reactions to financial crises when they can be freely re-elected in the next term and when they cannot, due to a binding term limit (i.e., being a lame-duck politician).

By treating the periods with term limits on the incumbent politician as a plausibly exogenous setting that lowers political accountability, we find that a significant portion of re-regulations in the aftermath of financial crises is driven by private interests. Specifically, we detect that policy interventions occur both when politicians face a binding term limit and when they do not; however, the effect is almost four times larger in the former case. This result is robust to within-party estimations as well as controlling for various types of political heterogeneity across countries and specifically around crisis episodes. The further employment of a test recently proposed by Oster (2017) ensures that our findings are unlikely to be driven by other unobservable factors.

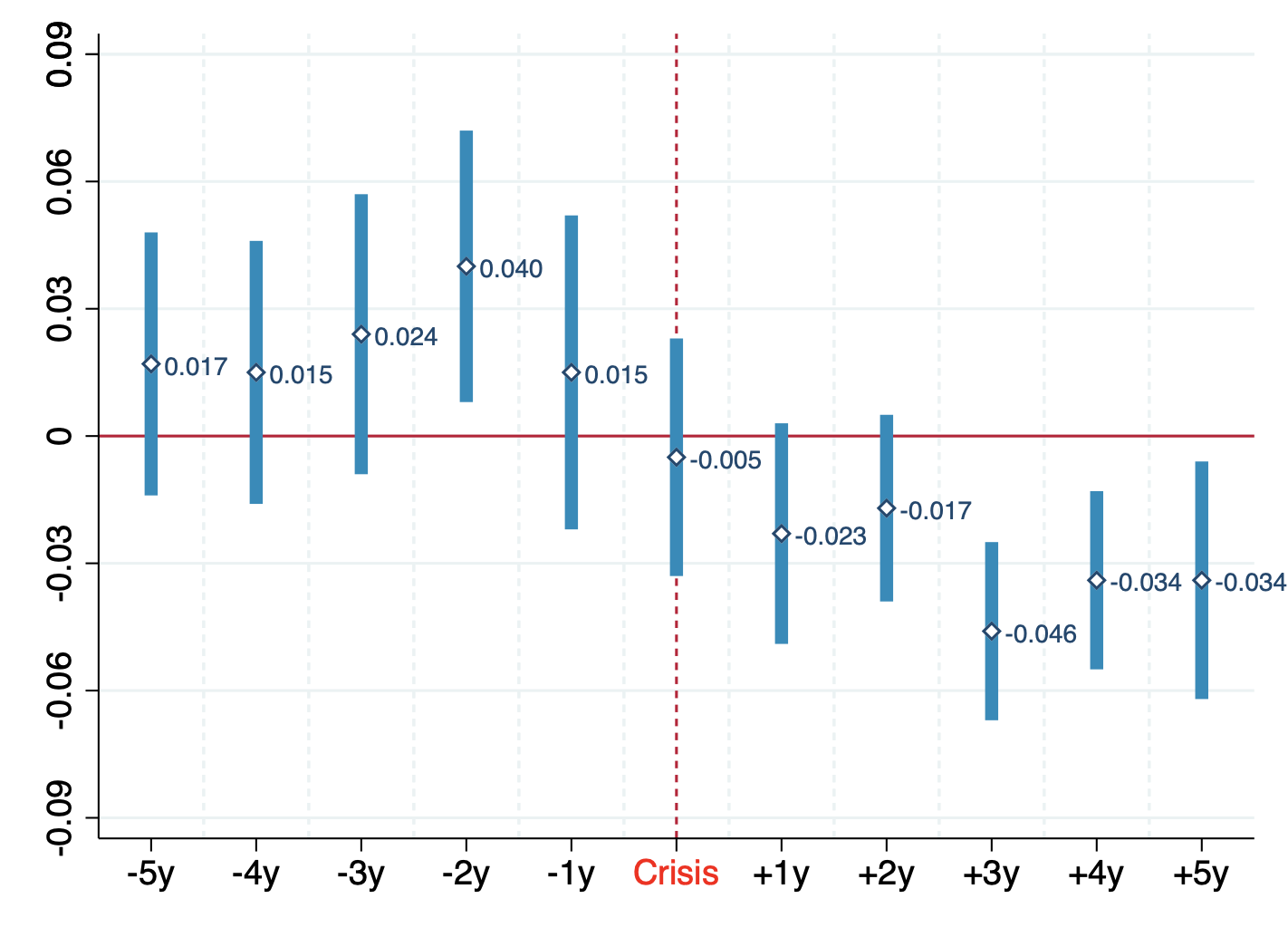

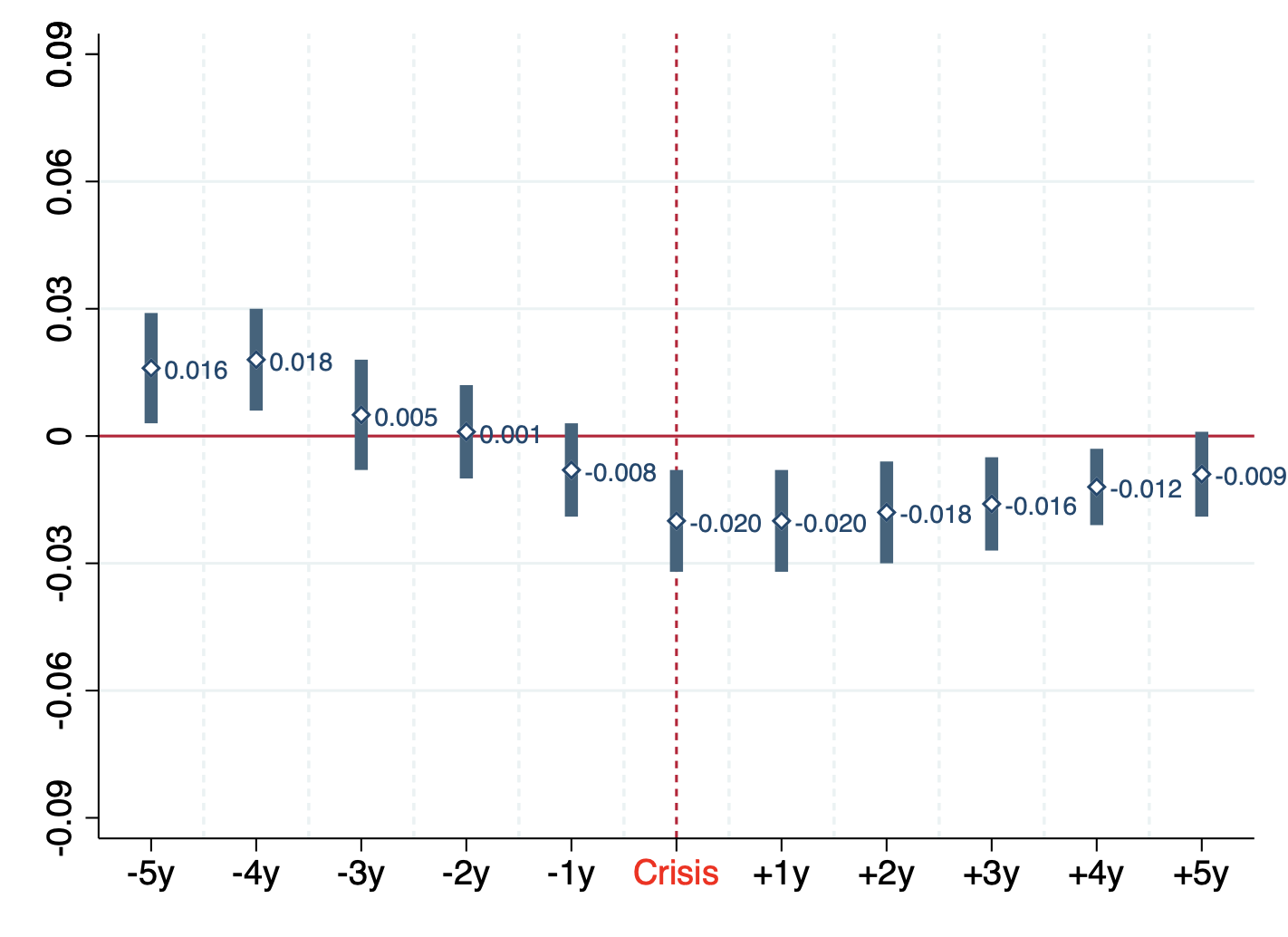

We additionally find that these privately motivated policies do not immediately follow financial crises, suggesting that they are not motivated by a need to resolve crises. Figure 2 illustrates this point by separating the effects of private and public interest channels of policymaking estimated within the same specification. On the one hand, the only channel that seems to instantly react to the crisis is the one that is publicly driven, which is consistent with the intuition that the public would require policymakers to generate an immediate response to the crisis in order to avert the financial doom. Furthermore, it gradually disappears over time, which is again consistent with the idea that these interventions are meant to be only temporary and do not represent permanent changes in a country’s financial policy stance. On the other hand, the private-interest channel becomes active much later (three years after a crisis), which makes it difficult to categorise these policies as a necessary response to the financial crisis.

Figure 2. Timeline for the effect of a crisis year (interacted with term-limits) on average financial liberalisation

A. Private interest channel

B. Public interest channel

Notes and Sources: The figure plots the estimates for β𝞃 in Panel A and in Panel B, both from the rolling specification in Equation 4 in Saka et al. (2020). Reform database is obtained by merging two subsets of observations from Abiad et al. (2010) and Denk & Gomes (2017). Data on financial crises is obtained from Laeven & Valencia (2018). Political variables are obtained from Cruz et al. (2018). Robust standard errors are clustered at the country level and confidence intervals are at 90% significance level.

Our analysis further shows that privately-motivated interventions mainly operate via the extensive margin of policymaking and, more importantly, emerge in different policy domains than those motivated by public interests. In particular, they are reflected in controversial areas such as increasing interest rate controls and raising bank entry barriers that are usually associated with rent extraction; and not in areas such as improving banking supervision or restricting capital controls that are usually associated with financial stability and considered more aligned with public interest.

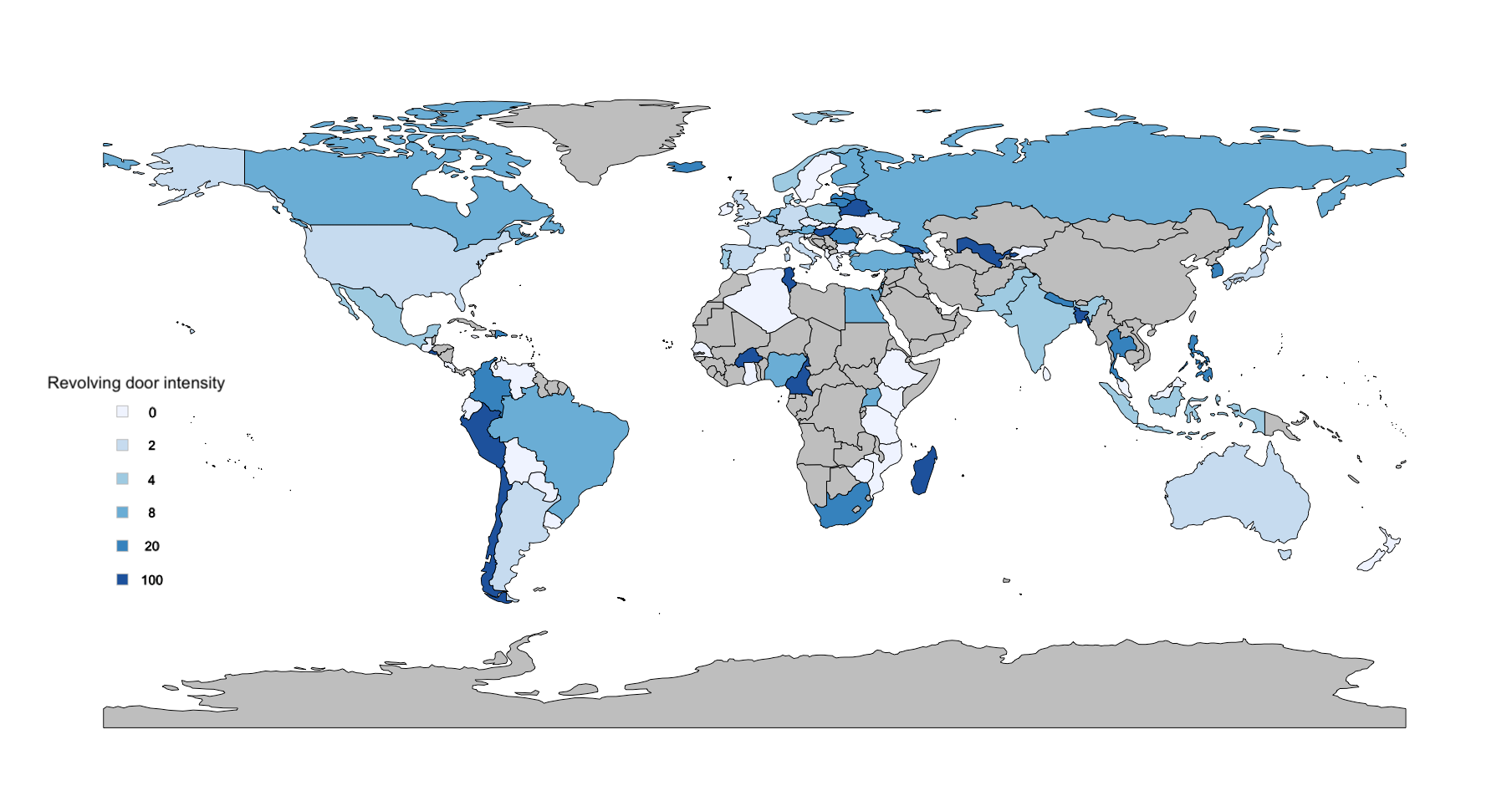

Figure 3. Revolving doors between financial and political institutions across the globe: continuous version

Notes and Sources: The figure maps each country depending on the fraction of its politically-connected banks which is the number of banks with at least one former politician on the board of directors divided by the number of banks for which there are data on board members in Bankscope as of year 2006. The measures are obtained from Braun and Raddatz (2010).

Finally, to illustrate one of the mechanisms behind policymakers’ private interests, we focus on three banking-related policy domains in which we can clearly lay out the preferences for incumbent banks: namely, bank entry barriers (proxying incentives to avoid competition), bank privatisation/nationalisation (proxying incentives to be bailed out by the government) and bank supervision (proxying incentives to be monitored by the government). Exploiting the intensity of the revolving doors between political and financial institutions across countries (which we derive from Braun and Raddatz, 2010; see Figure 3), we show that term-limited politicians further adjust their policies in ways that would be favourable to incumbent banks when they have a higher chance of pursuing a financial career after leaving politics. This suggests that political executives in their last term advance their own private agendas by resorting to financial repression that tends to create rent-seeking opportunities.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Financial Policymaking after Crises: Public vs. Private Interests, a discussion paper of LSE’s Systemic Risk Centre.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by lo lo on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Orkun Saka is an assistant professor at the University of Sussex, a visiting fellow at LSE and a research associate at LSE’s Systemic Risk Centre. His main research interests are in financial intermediation, international finance and political economy. He tweets @_OrkunSaka.

Orkun Saka is an assistant professor at the University of Sussex, a visiting fellow at LSE and a research associate at LSE’s Systemic Risk Centre. His main research interests are in financial intermediation, international finance and political economy. He tweets @_OrkunSaka.

Yuemei Ji is an associate professor in economics at University College London (UCL). Her interests cover three aspects: 1. international macroeconomics and the European monetary union; 2. behavioural macroeconomics; and 3. the Chinese economy.

Yuemei Ji is an associate professor in economics at University College London (UCL). Her interests cover three aspects: 1. international macroeconomics and the European monetary union; 2. behavioural macroeconomics; and 3. the Chinese economy.

Paul De Grauwe is a professor and the John Paulson Chair in European Political Economy at LSE. His research interests are international monetary relations, monetary integration, theory and empirical analysis of the foreign-exchange markets, and open-economy macroeconomics.

Paul De Grauwe is a professor and the John Paulson Chair in European Political Economy at LSE. His research interests are international monetary relations, monetary integration, theory and empirical analysis of the foreign-exchange markets, and open-economy macroeconomics.