The negative impact of the pandemic on small enterprises is well documented. In a two-month period, from February to April 2020, the number of active business owners in the US fell by 3.3 million, or 22 per cent, the highest change in recorded history. To mitigate the impact of these changes, economies implemented numerous crisis response measures, including revising their procurement procedures to reach smaller firms and increase regulators’ discretion. World Bank data reveal that in the recovery phase countries support small businesses with a variety of measures.

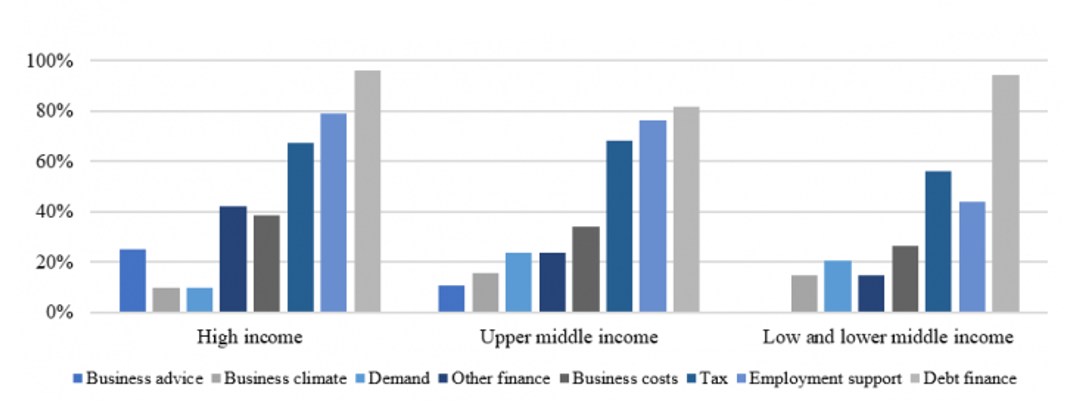

A closer look at the data shows that extending short-term finance is the most widely used type of support. New lending under concessional terms, delayed repayments, restructuring and rescheduling, credit guarantees with new schemes, and capital buffer safeguards – such as lowering capital requirements on banks and central banks’ actions to induce commercial banks to increase lending to business – are some examples of finance instruments used by various economies.

Figure 1 lists the most common measures adopted by countries at different income levels, displayed as the percentage of countries in that income group who have adopted at least one measure in each category. There is one clear difference between groups. As the second most commonly adopted set of policies, high and upper-middle income countries are relying on measures for job retention while low and lower-middle income countries favour tax-based measures. Wage subsidies, cash transfers to informal or self-employed workers, and financial support to digitisation efforts and re-skilling are some examples of employment support measures adopted so far.

Figure 1. SME support measures – percentage of countries by income group

Source: World Bank Group, Map of SME-support measures in response to COVID-19 and World Bank country and lending group classification.

As country after country shifts government support from early crisis response measures to recovery plans to bolster the post-pandemic economic rebound, there is a clear pattern emerging in the type of measures adopted by high-income economies and emerging markets. The former use a mixture of supply and demand-boosting components in their recovery programs, reaching households and businesses alike. The latter group finds it more difficult to target households and small firms, as these are often in the informal sector. The focus is hence on promoting recovery in specific industries or through tax-reduction measures that benefit larger formal firms.

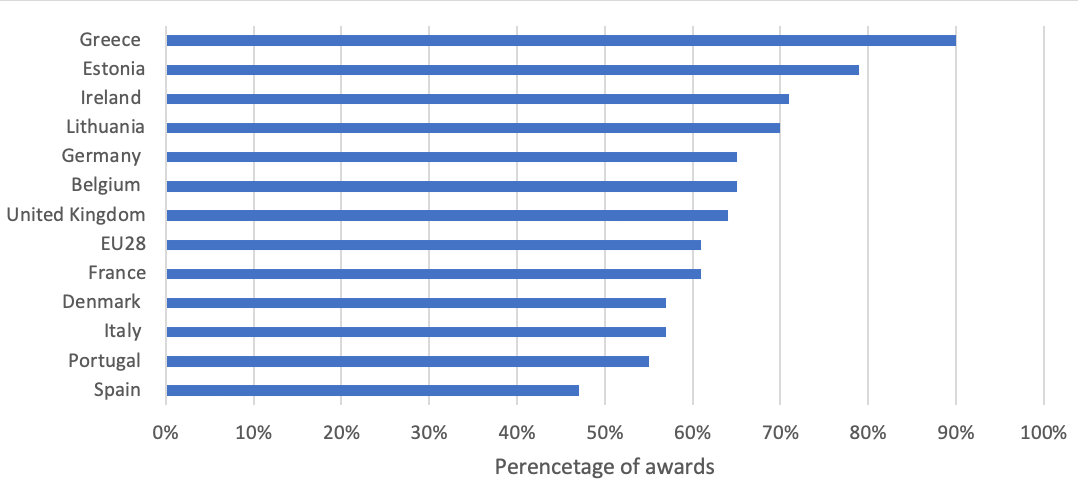

One measure to support small firms that is gaining traction in high-income countries is the introduction of COVID-specific procurement rules in their recovery plans. SMEs play a big role in public procurement. In the European Union (EU), a review of a sample of TED public contract award notices between 2011 and 2017 reveals that an estimated 61% of public contracts above the EU thresholds were awarded to SMEs. Considering the total contract value in this seven-year period, SMEs accounted for 33%. At the country level, the share of public contracts awarded to SMEs vary greatly: 90% in Greece, 71% in Ireland, 64% in the United Kingdom, or 47% in Spain (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Share of above-threshold contracts directly awarded to SMEs, by country (2011-2017)

Source: European Commission Analysis of the SMEs’ participation in public procurement and the measures to support it – 697/PP/GRO/IMA/18/1131/10226

Easier access to public procurement can help small businesses unlock their potential, while having a positive impact on the economy. A government contract may encourage small firms to invest more, expand employment and increase productivity thus helping to attain industrial development objectives (Geroski 1990; Ferraz et al. 2015). Higher participation of SMEs is for instance strongly correlated with an increase in labour productivity. The positive demand shock represented by winning a public procurement contract has higher potential effects on SMEs, as they are more demand-constrained businesses (Hoekman and Sanfilippo 2018). Awarding contracts to SMEs can facilitate access to finance by allowing them, for instance, to use the contract as collateral for a loan. A stronger participation of SMEs in public procurement also allows procuring entities to broaden their base of suppliers, and to improve the overall competition for public contracts.

Chile is one of few OECD countries that has taken concrete measures to help SMEs in procurement so far, announcing the implementation of the “Compra Ágil” in March 2020 as a fundamental part of its “Economic Plan to Overcome Coronavirus Emergency.” This new platform streamlines small public purchases (under 1500 USD) with the objective of promoting small business participation in public procurement. The Directorate of Government Procurement and Contracting of Chile also adopted multiple measures in order to facilitate the administrative processes of contracting authorities. Guidelines 34 in particular contains recommendations to public officers to reduce barriers to smaller companies’ participation. As of September 2020, the Slovak Republic Public Procurement Office is preparing two new guidances. The first one will support the participation of SMEs in small tenders after the COVID-19 health crisis. The second guidance will provide specific details to procuring entities on how to prepare conditions for the participation of SMEs in these tenders.

With a second wave of closures approaching in a number of countries, SMEs will need even more assistance. Public procurement provides a fast conduit for such government help.

| This is LSE's International Organisations Week. |

|---|

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Gene Gallin on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Erica Bosio is a researcher at the World Bank Group, where her work focuses on public procurement. Previously, she worked in the arbitration and litigation department of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton in Milan. She holds a Master of Laws from Georgetown University and a degree in law from the University of Turin (Italy).

Erica Bosio is a researcher at the World Bank Group, where her work focuses on public procurement. Previously, she worked in the arbitration and litigation department of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton in Milan. She holds a Master of Laws from Georgetown University and a degree in law from the University of Turin (Italy).

Joseph Lemoine is a private sector development specialist at the World Bank, where his work focuses on public procurement, business regulations, and justice reforms. Previously, he worked at the Paris office of Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP. He holds a Master of Laws (LLM) from Georgetown University, a law degree from Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and a political science degree from Sciences Po Grenoble.

Joseph Lemoine is a private sector development specialist at the World Bank, where his work focuses on public procurement, business regulations, and justice reforms. Previously, he worked at the Paris office of Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP. He holds a Master of Laws (LLM) from Georgetown University, a law degree from Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and a political science degree from Sciences Po Grenoble.