That the remuneration of top executives in large UK listed companies has grown much faster than average earnings since the early 1980s is hardly a surprise given the plethora of articles on top pay that have been published in the 40 years. Thomas Piketty has described this global phenomenon as “the rise of the super manager”, which he considers a major contributor to modern-day inequality.

In order to understand why top pay has risen so much faster than average earnings we investigated UK FTSE 100 company pay practices in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. We examined the data where they were available, but we also studied reports and historical documents and interviewed consultants who advised on payment systems throughout the period. Our work has recently been published in the journal Economy and Society.

We attribute the growth in intra-firm inequality to changes in the processes for determining pay in the early 1980s, which we describe as a move from “administered” to “outsourced” inequality. We identify a number of specific factors which have contributed to intra-firm inequality, including the use of stock-based pay for top executives and the outsourcing of lower paid jobs.

Until the early 1980s, internal company processes defined pay: CEOs and other senior executives were largely paid in the form of salaries which were determined according to internal job evaluation processes, including the well-known Hay system. By the late 1980s, the remuneration of top executives had been decoupled from all-employee pay and linked instead to external asset (i.e., stock market) prices with the growth in share-based reward packages. This was accompanied by the outsourcing of low paid work, and generally by the decline of trade unions and collective bargaining, which had helped to compress the pay gap between senior executives and ordinary employees.

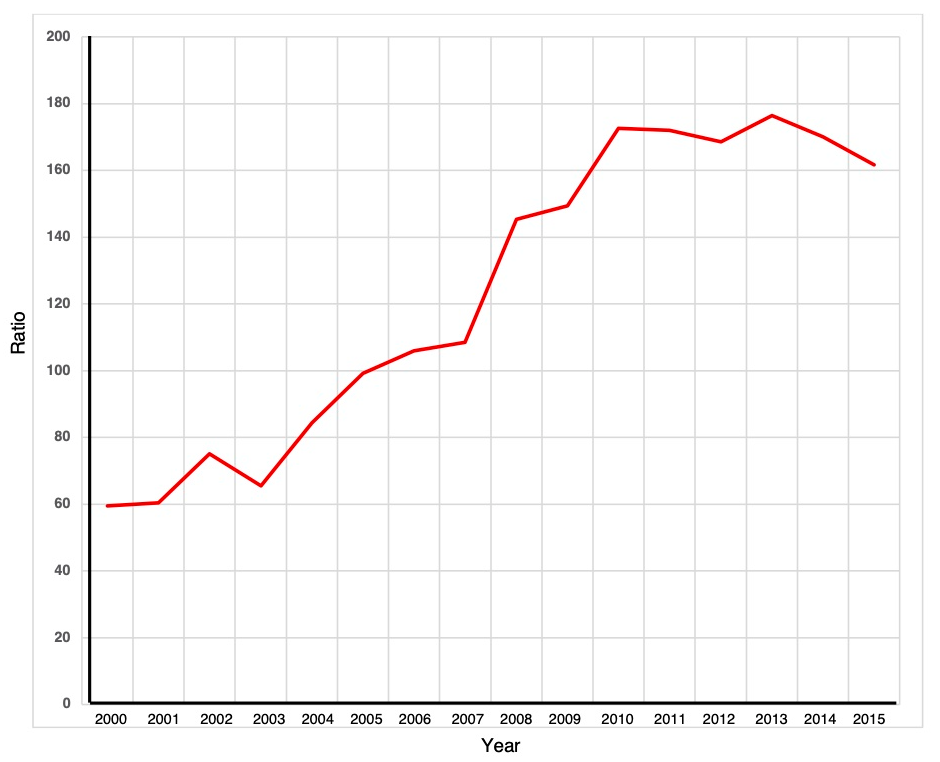

To illustrate the impact of share-based rewards on intra-firm inequality, Figure 1 charts the ratio of average total pay of FTSE 100 CEOs to average national wages for the period 2000 to 2015.

Figure 1. Ratio of median total pay of FTSE 100 CEOs to average national earnings, 2000-2015

In 2015 the ratio of median total pay of FTSE100 CEOs to UK average national earnings was 161:1 (£4,052,000 compared with £25,004). In 2000 the equivalent statistic was 59:1 (£962,145 compared with £16,172). The median salary of FTSE100 CEOs was £538,000 in 2000. By 2015 this had risen to £927,000, an annualised growth rate of 3.1 per cent, whereas FTSE100 CEO median total pay increased from £962,145 in 2000 to over £4 million, an annualised increase of 10.1 per cent. The difference between these two growth rates is largely attributable to the pervasive use of share-based incentives, which increased as a proportion of total pay from 39% in 2000 to 79% in 2015. According to data obtained from the Office for National Statistics during the same period the annualised increase in average earnings was 3 per cent and the retail prices index rose by 2.8 per cent per annum.

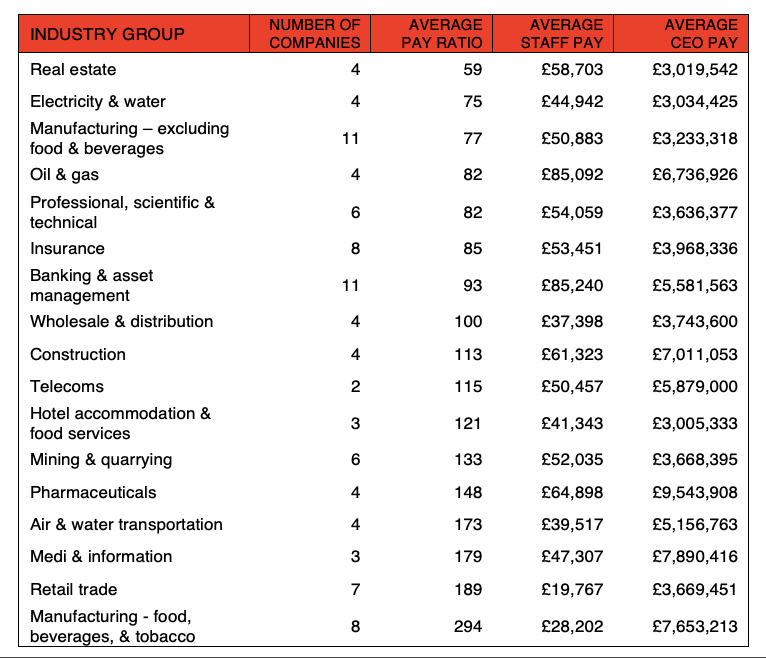

Table 1 compares the ratio of average CEO pay to average pay for FTSE 100 companies in 2015 by standard industry classification. The data exclude WPP plc because of the distorting effect of the staggeringly high pay of its CEO (£70.4 million in 2015) as well as pure investment companies. The variance on multiples is substantial from under 59 to 294. This is driven by both the denominator (average staff pay) and the numerator (CEO pay). Inspection of the industry categories reveals that this variance is unlikely to be explained solely by the variation in CEO earnings. Consider, for example, the banking and asset management sector (multiple of 93) with the retail trade (multiple 189). In banking and asset management, average staff pay is very high (£85,240) and CEO pay quite high (£5,581,563) compared with the FTSE100 average. In retailing, CEO pay is just under £3.7 million, but average employee pay is only £19,767. The banking and asset management ratio of 93:1 combines relatively low multiples in investment banking (high average earnings) and high ratios in retail banking (comparatively low average earnings). But it is high pay in investment banking which is a greater cause of public disquiet.

Table 1. FTSE100 pay ratios by standard industry classification, 2015

Ratios are of course affected by both the numerator (CEO pay) and the denominator (average staff pay). One way to reduce the denominator is to outsource low paid work. Many industries in the top half of the table do so. Low skilled work in banking and asset management (for example, catering, cleaners and security staff) are frequently outsourced. The relatively high average staff pay in the construction industry (just over £61,000) is because many lower paid jobs are done by subcontractors.

We believe that more needs to be done to moderate pay inequality in the United Kingdom. Public policy interventions might include reassessing the most appropriate denominator in pay ratios. From the beginning of 2020 it has become a statutory requirement for UK listed companies with more than 250 employees to disclose the ratio of the CEO’s pay to the median, lower and upper quartile pay of UK employees. Consideration should be given to extending the denominator in the pay ratio calculation to include all ‘workers’, a broader definition than ‘employees’ which includes agency and other casual workers. Companies should also be required to disclose the ratio of CEO pay to UK national average earnings as calculated by the Office for National Statistics, an objective, ‘non-gameable’ measure. We believe that a limit should be placed on the proportion of top pay which can be delivered in shares or calculated by reference to stock prices. A satisfactory degree of incentive alignment can still be achieved if 75-80 per cent of senior executive pay is delivered in cash. Executives should be expected to invest some of their own money in own-company shares. Finally, the government should consider whether large listed companies should be required to test levels of senior executive pay using systematic job evaluation, as was the case with the UK nationalised industries pay review bodies.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on The role played by large firms in generating income inequality: UK FTSE 100 pay practices in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Economy & Society

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Karen Uppal on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Alexander Pepper is professor of management practice at LSE’s department of management. He previously had a long career at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), where he held various senior management roles, including global leader of the human resource services consulting practice.

Alexander Pepper is professor of management practice at LSE’s department of management. He previously had a long career at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), where he held various senior management roles, including global leader of the human resource services consulting practice.

Paul Willman is an emeritus professor of management at LSE’s department of management and the academic director of LSE’s executive courses.

Paul Willman is an emeritus professor of management at LSE’s department of management and the academic director of LSE’s executive courses.