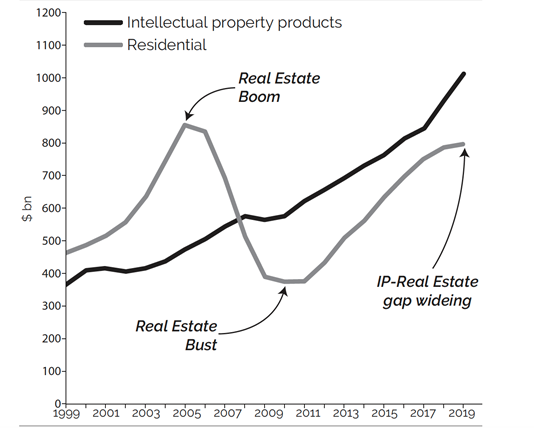

When the ideas inside our heads are worth more than the roofs above them, it’s a sign of the times. That is to say, investment in intellectual property – the business of ideas – is now worth more to the US economy than residential real estate – the business of bricks and mortar. This creates a dilemma for measuring the economy as what matters most risks being measured least, writes Will Page.

The twists and turns in the lines charted below offer a timely reminder in economic history. Only twenty years ago the tables were turned; residential real estate was not only worth more than intellectual property but poised to increase in value. But then the housing market collapsed, taking the world economy with it, kicking off a decade of convulsions that have brought us to where we are: a new normal where investment in the ideas inside us continues to outstrip that in the houses around us. Yet our ability to measure the contribution of our ideas remains worryingly limited.

Our ideas fall under the umbrella of intellectual property, essentially copyright, trademarks, and patents. Unsurprisingly, as the former chief economist at Spotify (and previously PRS for Music) my speciality is copyright as that’s what creates and captures the value of music. Perhaps, more surprisingly, almost a decade ago I worked with Jonathan Haskell to demonstrate to the bean counters that ‘music [was] seven times more valuable to UK plc than first thought’. That marked a beginning in personal curiosity about how we judge the state we’re in when what matters most is often intangible and that risks being measured least.

(Around the same time that work was published in 2012, a film scholar muttered to me that the way the government used to measure the economic contribution of cinema was to capture the value of just one movie theatre and use data from ice cream distributors to extrapolate across the country!)

Figure 1. Investments in the ideas in our heads are worth more than the roofs above them

Data source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

If measuring the intangible economy of ideas at home is problematic, how should we measure what they’re worth abroad? Post-Brexit Britain can be rightly proud of its music industry, a rare example of something it truly excels at exporting. For decades, Britain has been the only net-exporter of music besides the US and Sweden, thanks in part to the enduring popularity of its artists and songwriters.

Yet this presents two challenges. First, for statisticians, if capturing the true value of intellectual property at home is tough, measuring its value overseas is going to be tougher – imagine capturing the post-pandemic boost of British cultural exports when touring resumes if this activity was never being fully measured in the first place. For policymakers, intellectual property poses a Brexit-conundrum as copyright is governed by national treatment – meaning copyright and creativity is a rare example of what Britain excels at exporting, but never had a single European market to export to; therefore, never had a single market to leave.

Now, here’s why my passion for music economics – or ‘rockonomics’ – matters to the LSE: because music got there first. It was ‘first to suffer, first to recover’ from digital disruption and offers itself as a microcosm which everyone else can draw lessons from.

And here’s the biggest lesson of them all. When Spotify launched in the UK in the summer of 2009, music pivoted from measuring transactions – CDs sold across the counter – to tracking its actual consumption; not just the music being streamed and the device, time of day and source of those streams. No longer did we ‘put a record out’ on the physical shelf to see if demand drives sales; rather we made it accessible on a digital shelf and learned how it was consumed.

Now everyone else is playing catch up. The same pivot is happening in health (belonging to a gym doesn’t mean that you went to the gym today), transport (car sales last month do not tell you how many cars are on the road) and houses (knowing how people are living is more valuable than what property was sold). These are just three examples, (I could name a hundred more), where we’re seeing Tarzan Economics at play: let go of the old vine of knowing how something is sold and reaching out to a new vine to learn how it is consumed.

Policy makers who once relied on the old vine of car sales data to help determine transport policy now need to reach out to the new vine of smart cars that tell you how they are being consumed. The same goes for health policy; we can no longer hold onto the old vine of tracking gym membership and instead reach out to the new vine of health apps which track what we do to keep fit, not what we say we’ll do (especially in January!) And housing needs to let go of the old vine of simply counting property transactions, as what matters more is who is living in those homes and how they’re living.

Music was the canary in the digital coal mine. The first in, and first out. It woke up to the illegal file sharing site Napster in 1999 and spent the first decade fighting change by suing consumers, sites, and internet service providers alike, and the second embracing it and beating piracy at its own game with Spotify.

Now, due to the accelerated pace of disruption that’s resulted from the pandemic, we’re all facing our Napster moment. We all need to let go of transactional data and grab onto an understanding of consumption. We all need to realise what matters most – our ideas and our actions, are all too often what’s been measured least.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the book Tarzan Economics: Eight Principles in Pivoting Through Disruption, Simon & Schuster UK (2021)

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Eric Nopanen on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy