Many governments consider carbon taxation an efficient tool to reduce carbon emissions, but it can negatively affect welfare in terms of emission reductions versus reductions in output. So, how can carbon taxes be best introduced? In a new study using evidence from Mexico, Mattis Bös, Negar Matoorian, and Kasper Vrolijk show that when governments cannot select the most optimal policy –simply taxing some energy sources but not others – this may have substantial implications on how emissions and output, and eventually welfare, are affected.

Many governments consider carbon taxation an efficient tool to reduce carbon emissions. At present, close to 61 carbon pricing initiatives have been introduced or are scheduled. However, carbon taxation can negatively affect welfare and governments may want to introduce taxation in a way that reduces total emissions whilst limiting reductions in output. Which strategy should government pursue?

Targeting the largest sectors or emitters might not reduce emissions most effectively, because linkages between sectors determine how output and emissions in connected sectors are affected. Also, taxing the largest or most interconnected sectors might not necessarily reduce emissions most efficiently, because each sector may provide different trade-offs in terms of reductions in emissions and output.

In a recent paper, we identify an important third issue: carbon taxes may differ across energy sources rather than sectors. Often particular income groups, energy providers or sectors lobby governments for exemptions or reductions in carbon taxes on particular energy sources. As a result, carbon taxes are not uniform across energy sources. In this context, which sources should government tax?

We show that what we call emission centrality is an important tool to evaluate the effect of a tax on emissions and output. Emission centrality, which can easily be calculated using available production data and is therefore available to policymakers, captures three factors: how dependent sectors are on each other in terms of inputs and outputs, how changes in usage of inputs from other sectors changes emissions, and how energy sources are distributed across sectors. With this new measure at hand, we evaluate the implementation of carbon taxation in Mexico.

Insights from Mexico

In 2014, Mexico introduced carbon taxation—one of the first emerging economies to do so. An important feature of the Mexican context is that carbon taxation was implemented inefficiently because of political economy pressures. The government initially proposed a uniform carbon tax across all energy sources, but after consultations with interest groups, the tax was levied differently across different fossil fuels, exempting some. While natural gas was exempted, oil was taxed relatively high and coal only minimally.

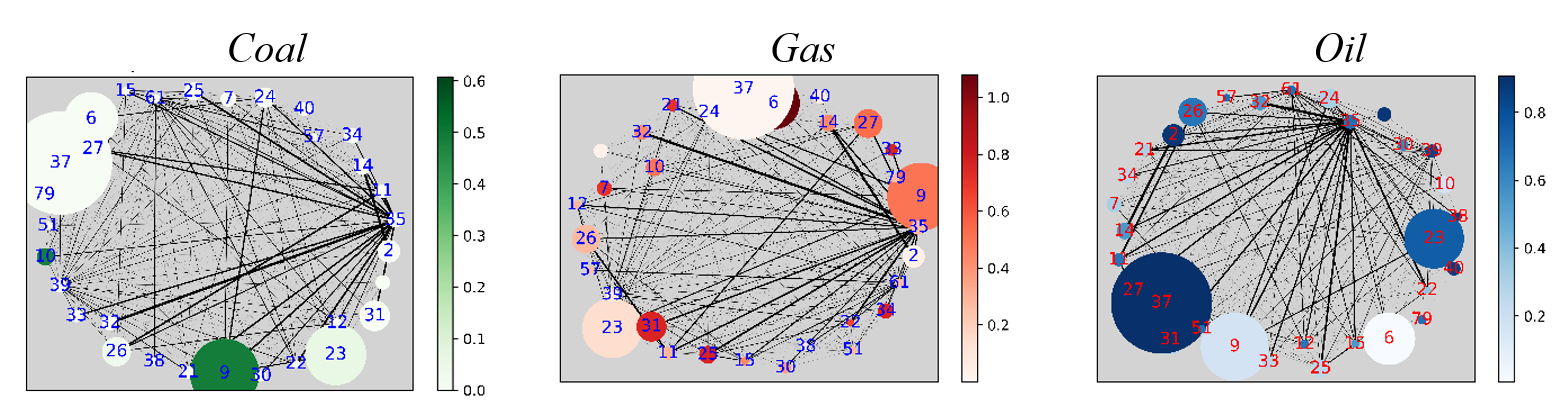

Which energy source government taxed and which one it excluded had a significant bearing on which sectors were affected. Figure 1 illustrates three sources of energy (gas, coal, and oil), the size of emissions by sector (node size), and the share of the energy source in total emissions by sector (node colour). It shows that that different energy sources (and their emissions) are located differently across the network of economic activity, suggesting that taxing some energy source but not others affects sectors differently.

Figure 1. Emissions intensity and distribution within the network of sectors in Mexico

To evaluate the welfare implications of selecting some energy sources but not others, we develop a simple measure of emission-output trade-off, which measures how much aggregate emissions are reduced relative to aggregate output. The measure of emission centrality allows us to understand the effect of a tax on total emissions and output, and the trade-off measure allows us to pinpoint which tax is most efficient in terms of trading reductions in emissions with reductions in output. Generally, we find that sectors that provide the best emission-output trade-off are generally those that are most emitting. They see the largest reductions in emissions and output from the tax, although they are not necessarily the most central in the production network.

More specifically, using our measure, we show that the political economy effects that made a government abandon a uniform carbon tax and instead tax only some energy sources resulted in welfare reductions. Implementing the proposed uniform policy would have provided 30% higher emission reductions, while the output reduction would be 21% smaller. We also find that the government could have implemented a more optimal carbon taxation than it initially proposed, which would have decreased emission reductions by 87%, in return for a 99% smaller fall in aggregate output.

Takeaways

Our analysis suggests that, when governments and researchers evaluate carbon taxation, it is useful to model carbon taxes as a charge on the emissions of individual energy sources rather than on sectors. We also show that there are substantial welfare gains to be made by taxing some energy sources but not others and that when a government is constrained in taxing energy sources this may result in welfare reductions in terms of lower emission reductions and higher reductions in output.

Our findings provide additional insights to the ongoing debate on carbon taxation. Although there are clear differences in the emission-output trade-off between energy sources, our findings on Mexico suggests that, in the aggregate, carbon taxes reduce emissions more than output, regardless of which combination of energy sources is taxed. However, we do find unequal effects from carbon taxation across sectors, which suggests that there may be a need for governments to selectively subsidise certain economic activities to counterbalance large reductions in output from the tax.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Selective Carbon Taxation in Production Networks: Evidence from Mexico.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.