Consumer education does not always reduce the potential harm of misleading advertising. When people are trained to detect a specific deceptive advertising tactic, they may become blind to other equally deceptive tactics employed by advertisers. Andrew Wilson writes that a more general training that encourages scepticism towards ads can be effective in helping people spot more deceptive tactics.

It’s both a common bit of received wisdom and well documented finding that marketing communications are replete with misleading, deceptive, and outright fraudulent information. The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC)’s periodic study of the matter found in 2017 that over 40 million consumers, or 15% of the US adult population, were victims of fraud or deception that year. The FTC itself, along with several consumer welfare organisations (e.g., TINA, Consumers’ Union) have up-and-running programmes meant to address the problem of misleading advertising by informing consumers about the many deceptive tactics deployed by advertisers. These programmes are no doubt well-intentioned, and at first glance appear to be purely positive. However, there is more going on here than can be noticed at a single glance. Our research shows that training consumers to look out for some particular deceptive tactic comes with an unintended consequence: it makes them more likely to fall prey to other deceptive tactics than they would have been if they had not been trained.

My co-authors (Peter Darke and Jaideep Sengupta) and I see the world as consumer psychologists, and we see this situation as one where a consumer has many goals competing for their mind’s steering wheel. We expect that, among other goals, consumers want to arrive at accurate judgments about an advertisement’s message. So far, pretty straightforward. But consumers are also motivated to use the particular knowledge they have to avoid being tricked, and we know people really do not enjoy being tricked. Here we turn to our theoretical toolkit, and pull out two tools, the Persuasion Knowledge Model, and Goal Systems Theory. The first tells us that consumers are motivated to learn about the tactics included in the training offered by the likes of Consumer Reports. The second tells us that these motivations exist in a complex system of complementary and competing goals, and the training that activates a goal to detect a specific kind of tactic (e.g., an illegitimate expert), is also likely to turn off closely related detection goals for other specific tactics in that system (e.g., detection of a limiting footnote).

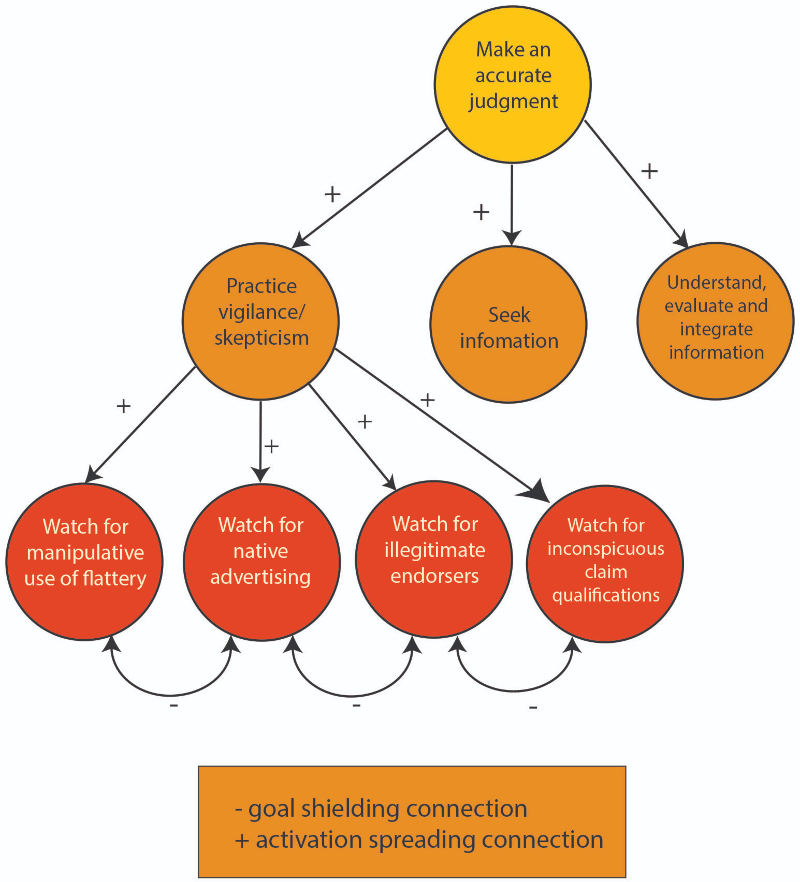

This pattern is called goal shielding, and in general, it’s functional. That is, goal shielding helps us to pursue one goal without being distracted by the many alternatives available. Imagine goals arranged in a hierarchy, where the top of the hierarchy is the most general vigilance goal (advertising scepticism); and the bottom comprises multiple vigilance goals for specific advertising tactics (e.g., watch out for illegitimate experts, watch out for important information hidden in footnotes, etc.). See the figure to help your imagination along. Finally, imagine these goals are connected, and that those connections come in two types: vertical connections between higher and lower-level goals that facilitate mutual activation, and horizontal connections between numerous specific lower-level goals where goal shielding happens.

Figure 1. Consumers’ competing goals

With this bit of theory laid out, we noticed that even though these trainings may be well intentioned, their designers seem unaware that the level of specificity in this goal system matters. If training is focused on getting consumers to detect a particular tactic, it would leave them vulnerable to all the other tactics an ethically challenged advertiser may deploy. In addition, the hierarchical nature of the goal system implied that encouraging a more general vigilance goal further up the hierarchy might work just as well, while avoiding the unintended consequence of making consumers more vulnerable to other tactics.

Our recent publication details the experiments we ran to test these ideas. We completed two experiments in which we trained consumers to detect deceptive advertising. In these experiments, we varied the type of training in terms of how specific (vs. general) it was, and therefore which level of the goal system was activated. Then we exposed our participants to another ad and tested whether they spotted the deceptive tactics it included. Taken together, the results of these experiments supported the idea that when training focused on a specific tactic, participants detected that tactic more than the control group. So, the training accomplished the intended effect. However, we also found that the specific tactic-oriented training led our participants to fail to notice a second deceptive tactic that was contained in the same ad. In contrast, the more general training that broadly encouraged scepticism towards advertising was effective in helping people spot both deceptive tactics used in the test ad.

This research suggests complications for viewing consumer education as a panacea for reducing the potential harm of misleading advertising. While it seems intuitively obvious to simply train consumers to better detect specific tactics, our findings suggest this can have unwanted and even harmful effects. Our findings suggest that encouraging consumer to be broadly sceptical of advertising was effective in encouraging them to detect a number of different misleading tactics. Even here other research suggests it is important to encourage an open and impartial kind of scepticism aimed at better determining the truth involved, rather than a more defensive perspective that rejects the truthfulness of advertising as a whole. Similar limitations have been raised for other means of curbing the harm of deceptive advertising, such as forcing companies to correct misleading advertising after the fact. Clearly a multi-pronged approach guided by research that is sensitive to the potential side-effects of such policies is required.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Winning the Battle but Losing the War: Ironic Efects of Training Consumers to Detect Deceptive Advertising Tactics, with Peter E. Darke and Jaideep Sengupta, Journal of Business Ethics.

- The post represents the views of the author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Joshua Earle on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.