Central bank independence, which increased over the past 50 years around the world, has recently come under pressure. There have been numerous studies about the consequences of independence for monetary authorities, but the causes of reform have received less attention. Davide Romelli investigates why and how central bank reforms come about, using a cross-country database on the timing of legislative changes. He identifies a number of challenges, including the increase in nationalism, the large build-up of sovereign debt, and climate change.

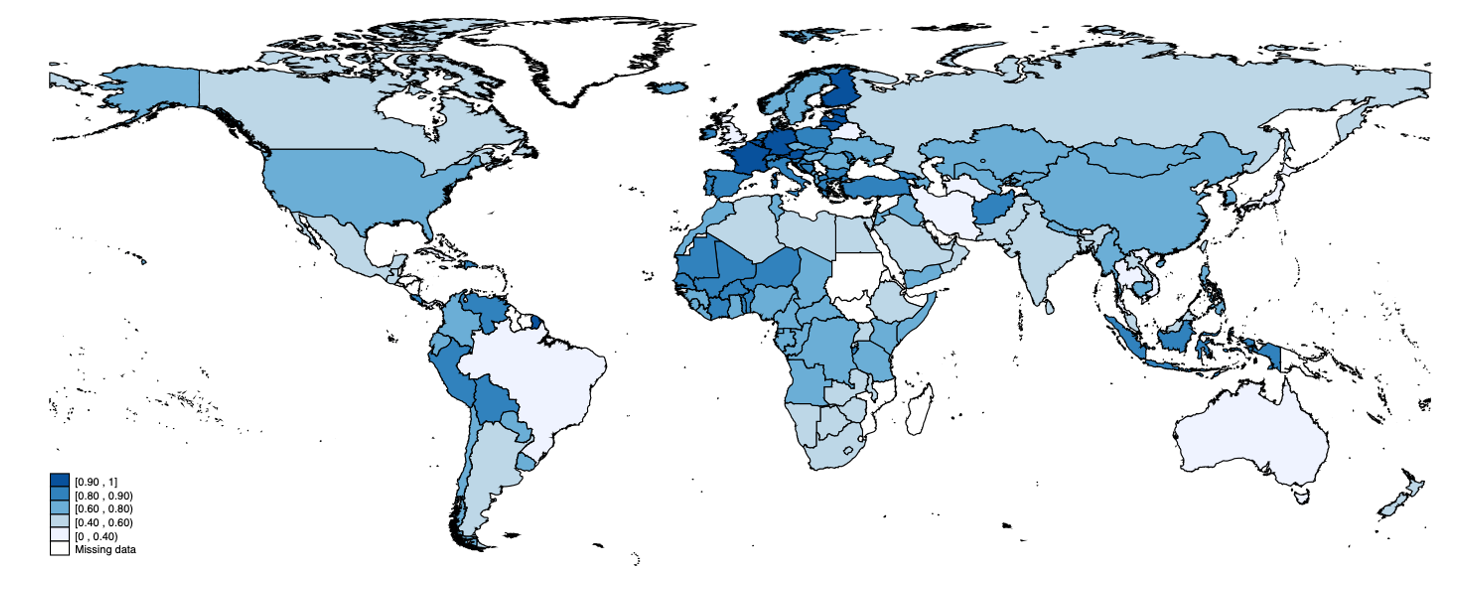

What explains the worldwide changes in central bank design over the past five decades? The four decades prior to the 2008 global financial crisis have been characterised by significant changes in the institutional design of central banks around the world, generally towards assigning monetary authorities a higher degree of independence from the executive branch. Yet, despite the large consensus on the optimality of this institutional arrangement in stabilising inflation rates, the degree of central bank independence still varies considerably across countries (see Figure 1). Moreover, the decade since the 2008 financial crisis has seen a new wave of reforms concerning, among other things, the involvement of central banks in financial supervision. In recent years, the autonomy of central banks has also come under pressure, particularly in countries with populist political movements.

Figure 1. Central Bank Independence around the world in 2017

Source: Romelli (2021)

A considerable body of work has investigated the consequences of assigning more independence to monetary policy authorities. However, the causes of reforms in central banking have received less attention. This paper investigates why and how central bank reforms come about. To do so, we introduce a large cross-country database on the timing of legislative changes in central banking for a set of 155 countries during the period 1972-2017. We construct a dynamic measure of central bank independence that allows for a more precise determination than previously possible of the timing and magnitude of reforms in central bank design.

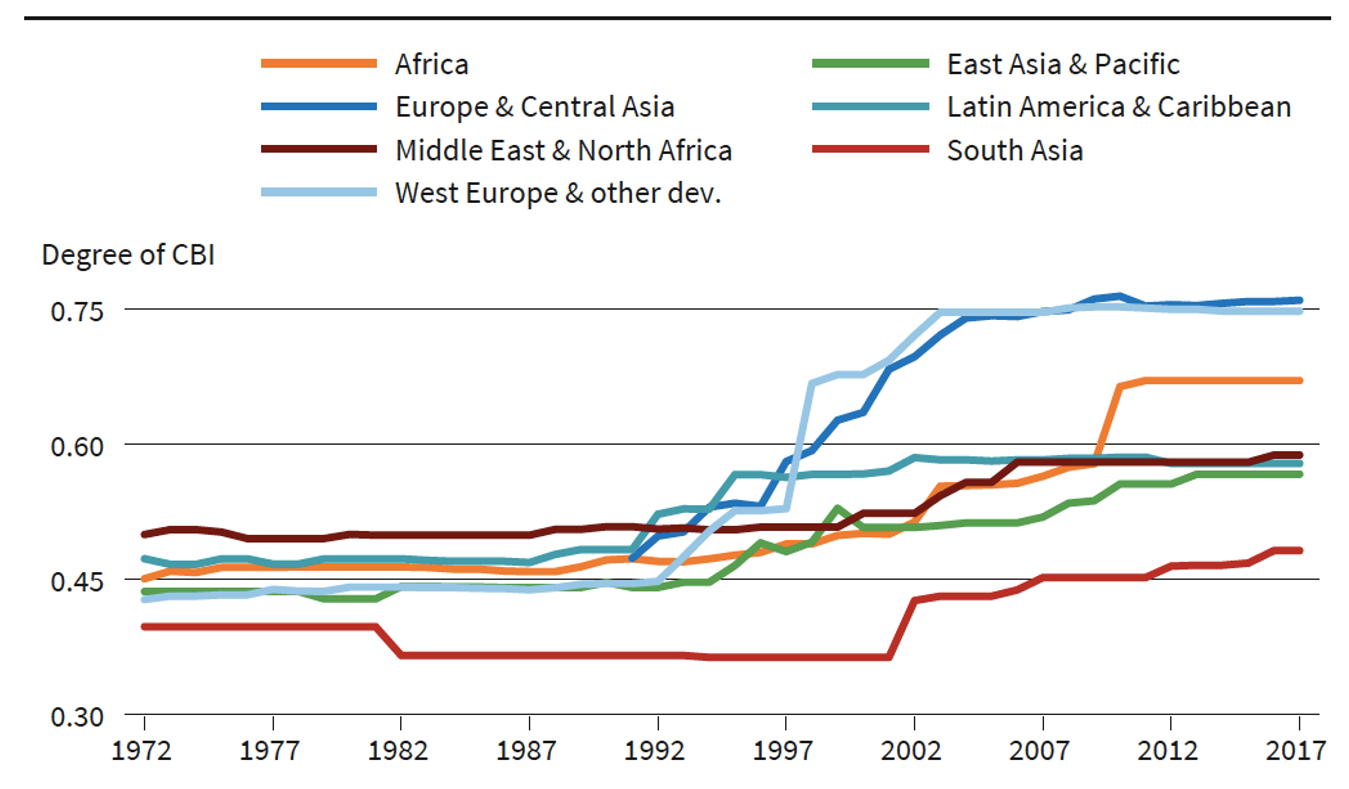

Employing this index, we provide a comprehensive overview of the evolution and timing of reforms in central bank design around the world. While central banks have become increasingly more independent over the last five decades, there is still a large variation across regions (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Evolution of central bank independence (CBI) by regions

Notes: This figure shows the evolution of the average index of CBI by regional clusters. Source: Romelli (2021)

We then use a political economy framework to identify five sources of reforms: (i) status quo bias, (ii) external inducements, (iii) crises and shocks, (iv) ideology and political factors and (v) economic conditions. The results show that the lagged level of central bank independence or status quo, as well as regional pressures are important in the reform process, as countries with lower levels of independence or those that are further from their regional average are more likely to adopt reforms that increase their level of independence. An external pressure to reform also comes from international institutions, as countries receiving an IMF loan or becoming a member of a currency union adopt reforms that increase the independence of their central banks.

Reforms that increase the level of central bank independence also follow periods of high inflation rates, suggesting central bank institutional design is endogenous to the inflation dynamics of a country. On the other hand, other types of crises such as systemic banking crises, currency or sovereign debt crises are not followed by reforms that increase the level of central bank independence. The data also shows important heterogeneities depending on the level of development. For instance, government fractionalization, cabinet changes or economic growth matter for the reform process among advanced economies, while external pressures and inflationary episodes are more important in developing economies.

The index constructed also allows for a more granular analysis of the magnitude and direction of reforms. This highlights important differences in the reform process. For instance, we find that financial crises are generally followed by reforms that decrease the level of central bank independence, while external inducements, regional convergence and status quo bias matter for reforms that increase the level of independence, but not those that decrease it.

The results obtained reinforce some widely held conclusions, such as the importance of external inducements in reforming central banks, but also shed light on some ambiguities in the literature such as the role of crises. The new index constructed not only sheds light on the endogenous evolution of central banks, but also provides a useful time-varying instrument of institutional design.

The endogenous evolution of central bank design is an ongoing process and the index and methods proposed in this paper can be useful in identifying how new challenges faced by central banks will affect their independence. For example, in our robustness checks we show that an increase in nationalistic political parties is likely to be followed by reforms that decrease central bank independence. This increased political pressure faced by many central banks due to the rise of populist movements across the world could further threaten the hard-won independence of these policy institutions. A second challenge faced by central banks nowadays can arise from the extensive asset purchase programs undertaken to respond to the last financial crisis and, more recently, the COVID-19 global pandemic. The large amounts of government debt held by many central banks increase the risk of fiscal dominance, i.e., situations in which monetary policy could be undermined and interest rates pegged at low levels to reduce the costs of servicing sovereign debt.

Finally, the highly debated impact of climate change on the institutional design of central banks might influence reforms in the years to come. So far, no central bank around the world has formally changed their statute to include environmental and climate goals. However, governments are pressuring central banks to take actions in this direction. For example, in March 2021, Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, stated that the Bank of England will have to support the government’s efforts to make the UK economy greener and achieve zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. While reaffirming the Bank of England’s longstanding inflation target, Rishi Sunak also said that monetary policy should now “also reflect the importance of environmental sustainability and the transition to net zero” (Financial Times, 2021).

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on The Political Economy of Reforms in Central Bank Design: Evidence from a New Dataset, presented at the 74th Economic Policy Panel Meeting, October 2021.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Samuel Regan-Asante on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

The world’s richest central bank, the PBOC, could hardly be less independent, yet it and the PRC have, together, created the most successful economy in world history. That the PBOC was founded by Mao Zedong adds to the irony.

The UK central bank is less independent comparatively today, than in the 1995 study.

Which individual factors are behind this?