With union membership rates in the United States declining over the last several decades, many in the labour movement are asking whether the young workers of today could help spark union revitalisation. Members of the Millennial and Gen Z generations have led recent hard-fought union certification victories at an Amazon warehouse in New York, an Apple store in Maryland, and Starbucks outlets across the country, which has reignited the hope that unions have a real future in the hands of today’s young workers. Tina Saksida and Rachel Aleks discuss how young people’s attitudes towards unions have changed over time and what this means for unions.

Millennials – individuals born between 1982 and 2000 and currently the largest generational cohort in the U.S. labour force – have been positioned as both the hero and the villain in the tale of declining union membership rates. On the one hand, younger generations may see labour unions as an antiquated “thing of the past” since basic employment and labour protections have existed for decades, but the labour movement might also be getting a “millennial upgrade,” with recent evidence suggesting that Millennial workers have been actively organising to achieve better working conditions and are responsible for the vast majority of recent gains in union membership (e.g., Alvarez, 2020; Chen, 2018; Schmitt, 2018). Either way, the current debate implies that Millennials’ attitudes towards unions are in some way unique and a departure from previous generations; we tested this assumption in a study recently published with our collaborator Aaron S. Wolf.

Generational clash?

The debate around Millennials (and, increasingly, Gen Z) and unions is occurring against the backdrop of a broader “generational clash” narrative advanced by both the management literature and the popular press. As just a few examples, Millennials have been called self-absorbed, assertive, individualistic, optimistic, and entitled (e.g., Chen, 2018; Kurian, 2017; Twenge, 2010), and workplaces have been adapting their management practices based on this assumption of a changing workforce. Similarly, there have been calls for unions to change their ways in order to accommodate younger generations’ shifting values (e.g., Kuriga, 2006; Smith and Duxbury, 2019; Timm, 2015), even though we currently do not have any compelling evidence that generational differences in union attitudes actually exist; like in the broader management literature, studies of generational differences in union attitudes generally suffer from serious design flaws that confound age and generational effects. Put differently, when researchers talk about generational differences, they may instead be capturing the effects of age or life stage. We were able to overcome this issue by using 40 years of data (N=104,742) from Monitoring the Future annual surveys of different respondents at the same life stage – specifically, twelfth graders or students in their final year of high school – to examine changes in youth attitudes towards unions over time and across generational cohorts.

Youth attitudes towards unions over time

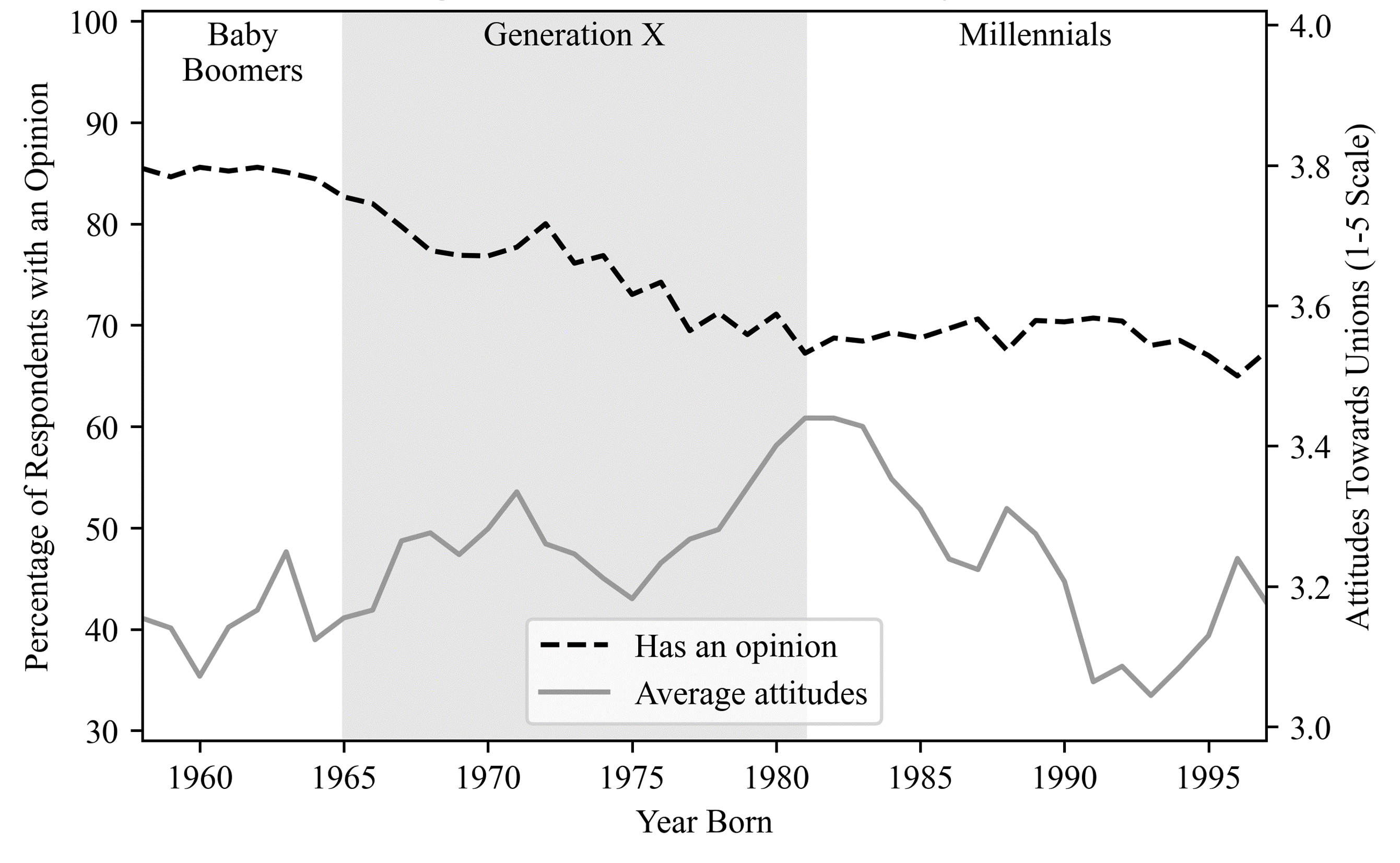

Figure 1. Percentage of US youth with an opinion about unions and average youth attitudes towards unions, by birth year

Notes: The x-axis in Figure 1 marks the respondents’ birth year, ranging from 1958 to 1997; this corresponds with data collection between 1976 and 2015. The left y-axis marks the percentage of respondents who had an opinion about unions (vs. no opinion), while the right y-axis marks average attitudes towards unions in terms of the job that labour unions were doing for the country, measured on a 1 to 5 scale (1=very poor; 5=very good), for those respondents who had an opinion about unions.

As shown in Figure 1, we found that the percentage of youth with an opinion about unions declined from 86% for those born in 1958 to a low of only 67% for respondents born in 1997. In other words, the proportion of respondents who were “agonistic” (i.e., those with no opinion about unions) more than doubled over the 40 years of our study, from 14% among those born in 1958 to 33% for those born in 1997. Among respondents who held an opinion, we found that average youth attitudes towards unions remained fairly constant – or even became slightly more favourable – over the 40-year period under study, although we also found that a high proportion of youth who held an opinion about unions were “fence-sitters” in that they held neutral views about unions (i.e., 3 on a 1-5 scale). This is revealing information for unions since – analogous to swing voters in elections for public office – both undecided or “agnostic” young people and “fence-sitters” could be instrumental in tipping organising drives in unions’ favour.

Viewing our data through a generational lens, we showed that Millennials held similar union attitudes to the generations that came before them, although our analyses also revealed that what was driving those attitudes had changed over time. For example, female and non-white respondents in younger generations held less favourable views of unions than their predecessors, which should be of concern to unions. Historically, unions have had greater success winning representation elections in bargaining units with a higher proportion of women and people of colour (Aleks, 2019; Bronfenbrenner, 1997), but our findings suggest that unions do not seem to be effectively communicating their utility to young women and young people of colour and may no longer be able to count on their support to the extent they had in the past.

What can unions do?

Contrary to the narrative (sometimes) advanced by the media and even the labour movement, our findings suggest that Millennials have not been “raised to turn their backs on labor unions.” And while the high proportion of contemporary youth who are either “agnostic” towards unions or “fence-sitters” may be alarming to unions, it also offers them a significant opportunity to make inroads among young people by strategically crafting their communication strategies and organising plans. Indeed, a key takeaway of our study for unions is that targeting pre-employment youth may be crucial to their future successes in organising and having highly committed members.

The decades-old union strategy of using slogans like “Labour unions: the folks who brought you the weekend” is unlikely to convince today’s young people, who largely take the notion of the weekend for granted. The question for unions, then, is: what is today’s “weekend”? While more research on this subject is needed, our findings suggest that unions may be well-advised to pursue a progressive agenda in their youth outreach efforts, highlighting their achievements in promoting gender and racial equality in the workplace and other social justice issues that resonate with today’s youth.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Hero or Villain? A Cohort and Generational Analysis of How Youth Attitudes Towards Unions Have Changed over Time, with Aaron S. Wolf, in British Journal of Industrial Relations.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image: Amazon labour union by Pamela Drew, under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 licence

When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.