With the costs of energy, housing, and food on the rise around the world, families are in desperate need of support. Some employers in the UK have been providing employees with food, discounts, and flexibility. Trade union membership is higher than in the past 30 years, but low-paid workers are underrepresented, and the government must provide targeted support for them. Sarah Ali and Teresa Almeida analyse business and government responses to the crisis and discuss the steps taken, how effective these forms of support have been, and the economic inequalities they have exacerbated.

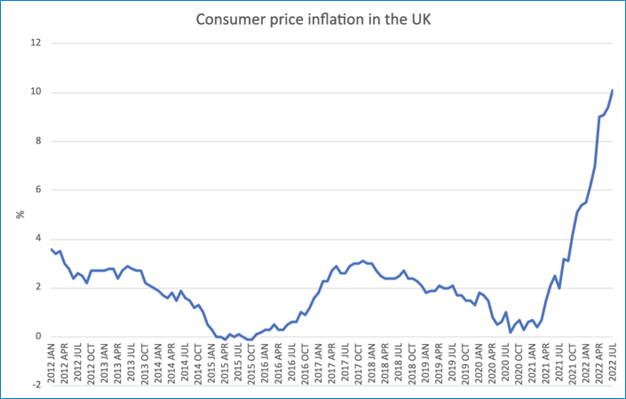

In the wake of economies reopening from COVID-19-related shutdowns, energy and global shipping costs have gone up. These financial pressures have been exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, particularly affecting industrial production in other parts of Europe and the import of Ukrainian agricultural goods. In the UK, these factors have led inflation to rise to 10.1% as of July 2022 (see Figure 1). In turn, this has increased the cost of living with housing, energy, and food costs higher than many people can afford – with the Bank of England forecasting inflation to soar even higher by autumn 2022.

Figure 1. Inflation rates for the last 10 years

Source: Office of National Statistics (ONS) Data

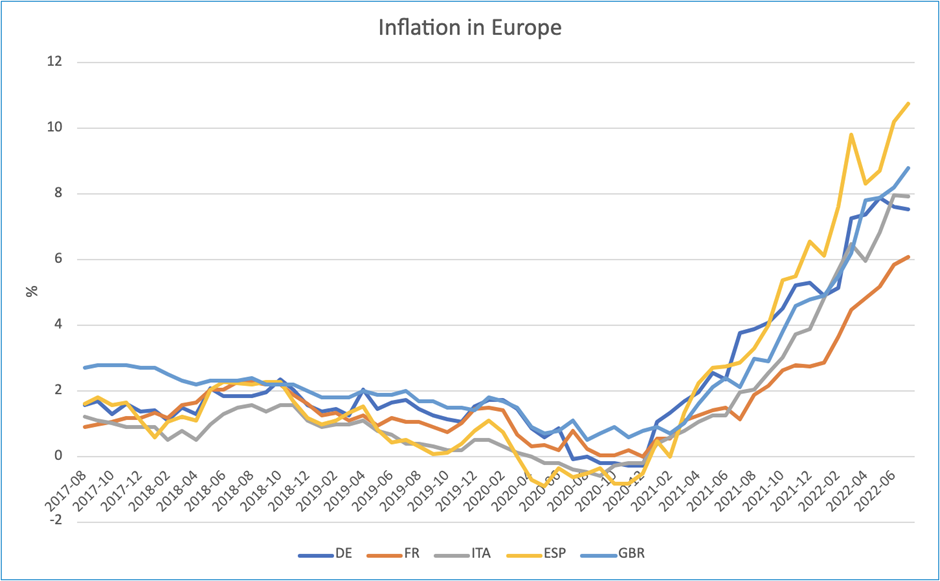

Similar rises to the cost of living have been experienced in other European countries (see Figure 2), forcing leaders to take decisive action to support citizens and workers.

Figure 2. Inflation rates in Europe for the last 5 years

Source: OECD Data

Across Europe, governments such as Germany and Spain have introduced policies to ease the burden of soaring costs, tackling areas such as housing and energy prices. The UK government has also stepped in with policies such as the Household Support Fund, but these government responses have largely been criticised as insufficient. While the UK response has been under fire for not being accessible enough, other European countries have been criticised for not sufficiently addressing the root causes of the cost-of-living crisis. Businesses in the UK are also facing pressure to provide better support to their employees, with historic levels of unionisation and industrial action. This analysis of government leaders’ and employers’ responses to the crisis provides a look into what steps have been taken, how effective these forms of support have been, and some of the economic inequalities they have actually exacerbated.

UK companies’ responses to the cost-of-living crisis

Today’s economic pressures have a large impact on food and transport costs. Prices for beef mince have risen by 32p, pasta by 17p, and vegetable oil by 14p – to name a few real examples.

As a result, some large companies in the UK have begun to offer support to their workers in affording these essentials, which causes inequalities between their employees and other workers who are self-employed or work for a small or medium enterprise. Supermarkets such as Sainsbury’s and Iceland have offered more employee discounts to ensure staff members are able to afford groceries, while businesses like the NHS Foundation Trust in Norfolk and Suffolk have set up a staff food bank. Other businesses like Leesman work to ensure more flexibility around commuting and working remotely so that employees can manage their transport expenses.

Despite the relief that these measures may offer workers in the short term, some argue that such support is not nearly as helpful as wage-related support. Companies across the UK have witnessed increasing pressure from trade unions calling for pay rises that match the level of inflation. Network Rail workers, for instance, created massive disruption to public transport this summer by striking in demand of increased wages. The RMT union received an offer of a 5% pay rise in a two-year deal, with the biggest rises going to the lowest-paid staff. However, the union are unsatisfied, as the offer did not even reach their minimum of a 7% increase.

Across other industries, unions have also played an important part in securing support for workers facing the cost-of-living crisis. At British Airways, Unite and GMB unions demanded that pay be reinstated to pre-pandemic levels after a 10% cut. The company offered its workers pay rises in response to striking workers and the threat of further action. These unions also went on to achieve wins for salary increases at Barclays and NatWest. BT Group workers have voted overwhelmingly in favour of industrial action as well, after employers introduced a low flat-rate pay rise worth 4.8% in the face of inflation expected to hit 11%. This, contrasted with the 32% pay increase received by BT’s chief executive, has pushed workers to strike for the first time in 35 years. Such historic levels of unionisation and strike action make clear the support that workers want the most in the face of today’s economic crisis: fair pay rises. They also emphasise the power of trade unions, and the potential they may hold for solving this crisis.

Unionisation in the UK

For the past five years, unionisation in the UK has been on the rise. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, a “wave of strikes and union organising campaigns” has taken place in the UK and globally, a drastic shift from the steady decline seen since Margaret Thatcher’s leadership. Fears of redundancies, working conditions and health risks to many frontline workers during the pandemic are some of the reasons thought to have led to greater interest in collective organisation. This has resulted in the surge in trade union membership. This has been particularly high in the public sector, with care workers and those in hospital professions increasingly joining unions as they are most immediately exposed to health risks. Against the backdrop of these pandemic-related concerns, the cost-of-living crisis has only increased union activism, with individuals now struggling to make a liveable wage. This also explains the historic numbers of workers voting to strike, with industrial action rising particularly in the public sector.

While these trends of growing unionisation and industrial action wins by the RMT, GMB, and Unite unions appear to signal positive change, not all workers in these sectors are gaining the same support. There is still a lack of representation for the lowest-paid workers in union membership, which suggests that pay rises and other forms of company support are not reaching the employees who may be struggling the most with surging living expenses. From check-in employees at British Airways to train operators at Network Rail, those in professional work are having their demands met by employers – but the support given to cleaners, security guards, and maintenance workers working in the same locations, but often under other contracts or employers, remains unclear. For instance, while the Network Rail pay rise was offered in July, outsourced railway cleaners continued to strike as their company Churchill refused to raise their wages.

However, beyond making demands of their employers, trade unions have also been calling on the UK government to take more action in the face of the economic crisis. Unions such as the RMT have called on the government to have a more active role in pay negotiations, criticising the lack of funding for public sector pay settlements by the government. Nadhim Zahawi, the UK’s chancellor of the exchequer, has not given assurance that the government will provide this funding. Looking at these demands by trade unions, support for workers does not depend solely on the decisions of employers, but on the government’s response to the cost-of-living crisis as well.

The UK government’s response to the crisis

Boris Johnson’s government have taken some significant steps to address the hardships created by high inflation levels for their citizens. One of their biggest measures has been raising the National Insurance threshold from £9,880 to £12,570, meaning that more than 70% of British workers will have to pay less National Insurance. This move will save millions of workers up to £330 a year. The UK government have also introduced a 25% windfall tax on oil and gas firms for a year. This money, paid by large oil and gas companies such as BP, will then be put towards providing more payments to households struggling with energy bills.

Payments that have already been made include a £400 energy bill discount to every household, a one-off £650 payment to households on benefits, as well as an extra £300 fuel payment to pensioner households this year. Further, as part of the government’s Household Support Fund, £1bn has been allocated to help poorer families with essential expenses such as food, clothing, and utilities. While these measures will ease the economic burden on many in the UK, yearly energy bills for the average household are expected to hit more than £3,600 in 2023 meaning they will not be enough to keep up with surging costs.

Other European governments

Other governments in Europe have provided focused support for residents in the areas that are costing them the most during this economic crisis, such as fuel costs. In Germany, residents have access to all public transport for June, July, and August this year with a single €9 ticket. Similarly, the Spanish government have recently declared that all commuter services and medium-distance train journeys will be free, in addition to the current 30% discount on all public transport. By making public transport more affordable, governments have been reducing the pressure on their citizens to travel by car at a time when fuel prices have been soaring.

Given the rise in rent prices, housing is another area that some European governments have stepped up to support. In Spain, the average rent increased by €636 per year as of February 2022. To combat this, Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez imposed a temporary cap on rent increases until July of 2022, limiting increases beyond 2% of properties’ previous rental prices. Not only does this move aim to curb high costs of rent for Spanish residents, but it also aims to reduce the increase in inflation rate in the country as well.

Perhaps witnessing the steepest inflation rate today is the price of energy, which most European world leaders are tackling through tax cuts for residents, one-off payments, and limitations on price increases for energy companies. Countries such as the Netherlands, Poland, Germany, and France have reduced taxes on electricity, petrol, and heating. These countries have also offered one-off payments and subsidies to low-income households to support them in paying energy bills. Spain, like the UK, has introduced a windfall tax on energy companies aiming to raise €3bn. Similarly, France has capped wholesale energy price rises at 4%. These measures provide direct support to families struggling to keep up with increasing energy costs, while limiting the ability of energy companies to continue to raise prices and rake in profits.

How does the UK measure up?

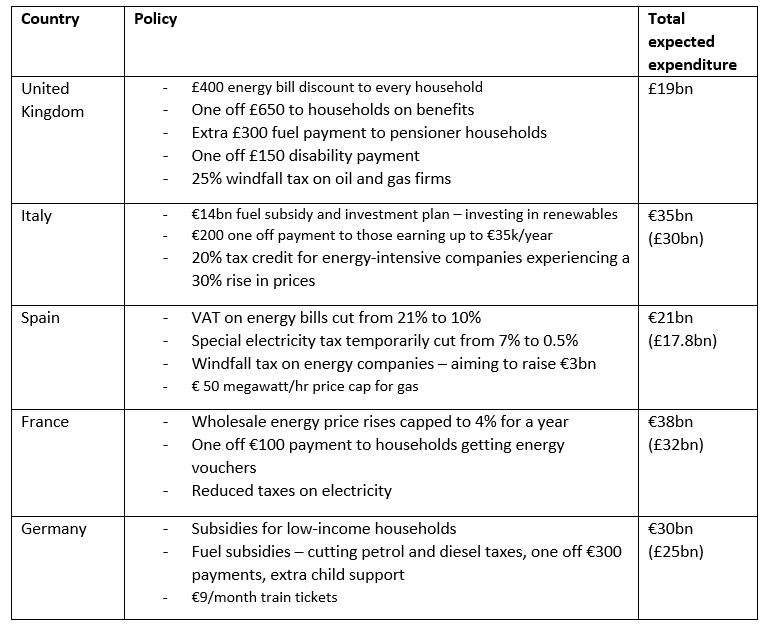

Despite spending an estimated £19bn on combatting the cost-of-living crisis, the UK government’s response is still lacking, especially in comparison to other European countries. Figure 3 compares the measures taken by the UK and other European governments to tackle energy costs. Price caps have been introduced in Spain and France, and discounted public transport in Germany. In contrast, the UK has seen an unprecedented 54% increase in the energy price cap, and public transport fares are on the rise as well.

Figure 3. Government policies to tackle energy costs

Source: Pickard-Whitehead, Left Foot Forward

Beyond the lack of action, the policies that have been introduced by the UK government have raised concerns regarding their appropriateness in tackling the crisis. For instance, one-off payments like the £400 energy bill discount from the UK government have been criticised for putting larger families at a disadvantage, as lump-sum payments provide all households with the same amount of money regardless of how many people will have to share it. Reportedly, it has also been extremely difficult for vulnerable people in the UK to access the Household Support Fund promised by the government due to convoluted application processes. These issues point to the larger problem that people in the UK are continuing to struggle with the cost-of-living crisis despite the steps taken by the government – and this is especially true for low-income households.

Not only is the UK government facing the challenge of providing more efficient and substantial support to its people, but of providing support that will prove sustainable in what is forecasted to be the longest economic recession since 2008.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Alistair MacRobert on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.