On top of the energy price guarantee costing about £60 billion over the next six months, Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced another £60 billion to reduce energy bills for businesses, plus £45 billion of corporate, payroll, and income tax cuts focused on the wealthy. These tax cuts and spending increases exceed those implemented during the pandemic, and they send government debt on an unsustainable trajectory. John Van Reenen believes a reckoning will be unavoidable. He writes that policies for good growth are a long slog, a marathon of difficult supply-side reforms and not a mad dash for growth.

| #LSEUKEconomy |

|---|

Labour’s 1983 manifesto was dubbed the “longest suicide note in history” and the party was soundly trounced by Mrs Thatcher in that year’s general election. On Friday 23 September 2022, Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng delivered his first “mini-budget”, which, despite his best intentions, may deliver the same disservice to the Conservatives.

On top of the energy price guarantee given to households by new prime minister Liz Truss costing about £60 billion over the next six months alone, the Chancellor splashed out another £60 billion to reduce energy bills for businesses plus £45 billion of corporate, payroll and income tax cuts, squarely focused on the wealthy. Altogether, these tax cuts and spending increases exceed those implemented during the pandemic, and they send government debt on an unsustainable trajectory.

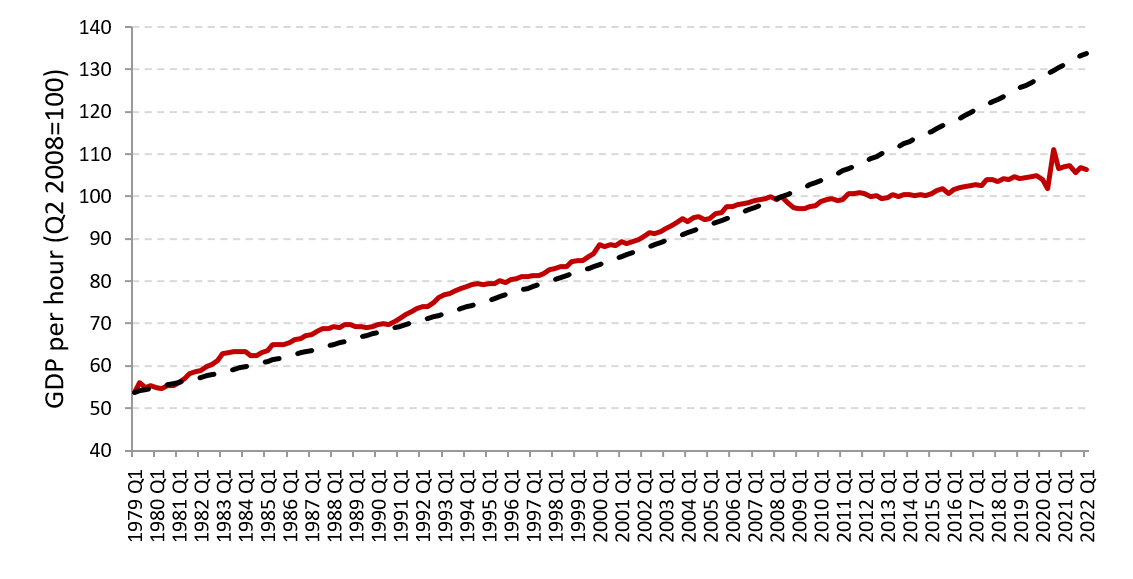

Chart 1. The great British productivity slowdown

Note: ONS, Quarterly output per hour worked whole economy chained volume measure (CVM) index (2008 Q2= 100). The dashed line is predicted value after 2008Q2 assuming historical average rate of 2.1%. Table 32. (Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.)

The rationale for this largesse is to stimulate growth. I concur with the Chancellor that this is our major problem. But tax cuts are just a quick-fix sugar-high – they do not deal with the UK’s fundamental problem of miserable productivity growth. Since the global financial crisis of 2007-09, UK output per hour has grown five times more slowly than it did in the previous three decades (see Chart 1). The pain of slow productivity growth has been shared rather democratically: pay growth has stagnated for almost all wage earners including those at the top and in the middle.

Running a larger government deficit is sound policy when demand is low, there is excess capacity and interest rates are near zero. This was the case when the Conservatives returned to power in a coalition with the Liberal Democrats in 2010. Ironically, then Chancellor George Osborne embraced full-throated austerity and cut public investment at exactly the wrong time, damaging productivity. The same party is now launching a massive deficit expansion when interest rates are rising and inflation is in double digits.

Liz Truss boasts of rejecting orthodox economics by favouring debt-financed tax cuts. But the policies of expansionary contractions (Osborne’s austerity) and Brexit’s economic benefits (Johnson’s raison d’etre) were also fringe economic views. Standard economic expertise on these big issues has been denigrated and ignored. The “people in this country have had enough of experts” said former minister Michael Gove – and the results have been prolonged stagnation.

I support protecting households from the soaring gas prices caused by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. But the right policy would be to offset this cost with solidarity levies from better-off households and windfall taxes on energy-producing firms. Instead, we have huge unfunded tax cuts.

The government’s answer is that these tax cuts will generate supply-side growth. Common sense and reams of economic studies show that this is simply not the case. Many high tax economies like Germany and the Nordic nations are robustly successful and big tax cuts for top earners have no clear relationship with growth (although they definitely increase inequality).

The current government seems entranced with US Republican ideas that have been mugged by reality. The idea that lowering tax rates will bring in more revenue is called the “Laffer Curve” after Arthur Laffer who was, well, having a laugh. It is possible that when top tax rates are extremely high (as the 90% plus rates immortalised by the Beatles), cuts can be self-financing. But no respectable economist believes this to be the case for current UK levels of taxation.

There are many ways that we could get good productivity growth. The UK suffers from chronic underinvestment especially in innovation and skills. Radical reforms of planning, property tax and green industrial policy could boost real supply-side growth. Here are some of my ideas for a proper plan.

By contrast, the new government has little detail on what its supply-side reforms will be. What we do know about their plans – such as the creation of more low tax, low regulation investment zones – are no game changers. The evidence shows that far from creating fresh investment, these will largely lead to geographical relocation of investment within the country at the expense of areas outside the zones.

The chronic disease of successive UK governments is the policy ‘attention deficit disorder’ that has created massive uncertainty, sapping economic growth. This was on full display in the mini-budget. In the face of a complete reversal of tax policy and a refusal to allow the independent Office for Budget Responsibility to analyse the implications of this ‘fiscal event’, it was left to the financial markets to provide judgement by driving sterling to a 37-year low.

Although prime ministers come and go – four in the last six years alone – what is consistent is policy failure. From premature austerity to the disaster of Brexit and now a revisit of the ill-fated Barber Boom. To mix metaphors from Seamus Heaney and Karl Marx, history is rhyming, first as tragedy and now as farce.

When the inevitable reckoning comes, will the UK be able to rebuild or is the damage now too permanent and too deep? I am an optimist and believe a new “Marshall Plan” for real growth is possible and can be delivered if we show the kind of will on display during the COVID crisis to innovate new vaccines. But we must realise that policies for good growth are a long slog, a marathon of difficult supply-side reforms and not this re-run of the mad dash for growth.

Explore our dedicated hub showcasing LSE research and commentary on the state of the UK economy and its future.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Timo Wielink on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

I am not an economist but possess some sound common sense something missing from this mini budget. Given the market response including the further decline in the value of the pound, this government needs to deal smartly with the issues requiring attention highlighted in your article or the government will fall as with Mr Johnson. The clock is ticking

Excellent rapid response to a very foolish budget. I call it Post-Truth Economics, which is characterized by deliberately ignoring economic expertise, justifying policies by half truths and cherry-picked examples, and appearing strong willed and confident, especially when telling lies.

A big shock to a fragile global financial system. This is disaster capitalism at its most destructive extreme: create the disaster and profit from it.

Great piece, the ‘mini-budget’ strikes me as a pandemic policy created by a group of anti-vaxxers.

Having worked for a large US listed multi-national and then a small UK PLC I saw a marked difference in investors’ treatment of the two companies — US company did not pay a dividend and was expected to plough all cash generated back into the business to drive growth; UK company was required to pay a dividend (by institutional investors concerned about cashflow into their funds) and was therefore actively discouraged from making investments in the future that paid back in anything longer than the reporting period (hence why redundancies in UK companies tend to drive share prices up). Look at the recent debates about lack of listings, especially of tech companies, in London because London investors are seen to be wary of the longer term returns that tech startups imply. I believe these are some of the main drivers for lack of growth and stagnation in the UK, how it can be fixed is less clear.

Much is made of UK productivity. Fernald and Inklaar show that this it is not as important an issue as is made out to be. Casual empiricism also suggest that they may be correct.

Fernald, John, Robert Inklaar. 2022 “The UK Productivity “Puzzle” in an International Comparative Perspective,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2022-07.

Abstract:

The UK’s slow productivity growth since 2007 has been referred to as a “puzzle”, as if it were a particularly UK-specific challenge. In this paper, we highlight how the United States and northern Europe experienced very similar slowdowns. The common slowdown in productivity growth was a slowdown in total factor productivity (TFP) growth; we find little evidence that capital deepening was an important independent factor. From a conditional-convergence perspective, most of the UK slowdown follows from the slowdown at the U.S. frontier. From the mid-1980s to 2007, the UK’s relative productivity level moved closer to the level of the U.S. and northern Europe, driven by essentially complete convergence in market services TFP. In contrast, manufacturing lost ground relative to the U.S. frontier prior to 2007, and remains far below the frontier. The relative ground lost after 2007 is modest—cumulating to about 4 percentage points—and is largely attributable to somewhat unfavorable industry weights and industry-specific issues in mining, rather than a systematic UK competitiveness problem.

In the US, productivity (output per hour) got a lift from 1995 to 2005, due to IT.

Since 2005 it has returned to its usual trend, as diminishing returns to the IT set in.

This isn’t a trickle-down budget, it’s a boost-up budget. The government has announced a radical set of policies to increase Britain’s prosperity. If this was the Chancellor’s ‘mini’ budget, I look forward to the ‘maxi’ budget.”