The idea that economic growth is incompatible with tackling the climate emergency is wrong, says John Van Reenen (LSE). He sets out how technological innovation and better management can bring about sustainable growth.

COVID-19 has revealed serious existing weaknesses in our politics and economy. As the UK emerges from the pandemic, we face a growth challenge of unprecedented scale. Whatever policy framework we adopt should unashamedly promote sustainable and equitable growth. To do that, we need new and better technologies and management practices.

Britain has been particularly hard hit by the pandemic, in terms of both deaths and the impact on the economy. Annual GDP fell by almost 10% in 2020, the greatest fall since records began. This makes us one of the worst-hit countries in the OECD.

Growth is not simply getting bigger. Increasing GDP by having a bigger population, or increasing working hours, is not obviously a desirable thing. What we need is productivity growth. Productivity measures how much more output can be generated per input, for example GDP per hour worked. History shows us that wage growth follows productivity growth over the long run. More productivity is like growing the economic pie: it gives us choices to spend more on public service, environmental protection, redistribution or private goods.

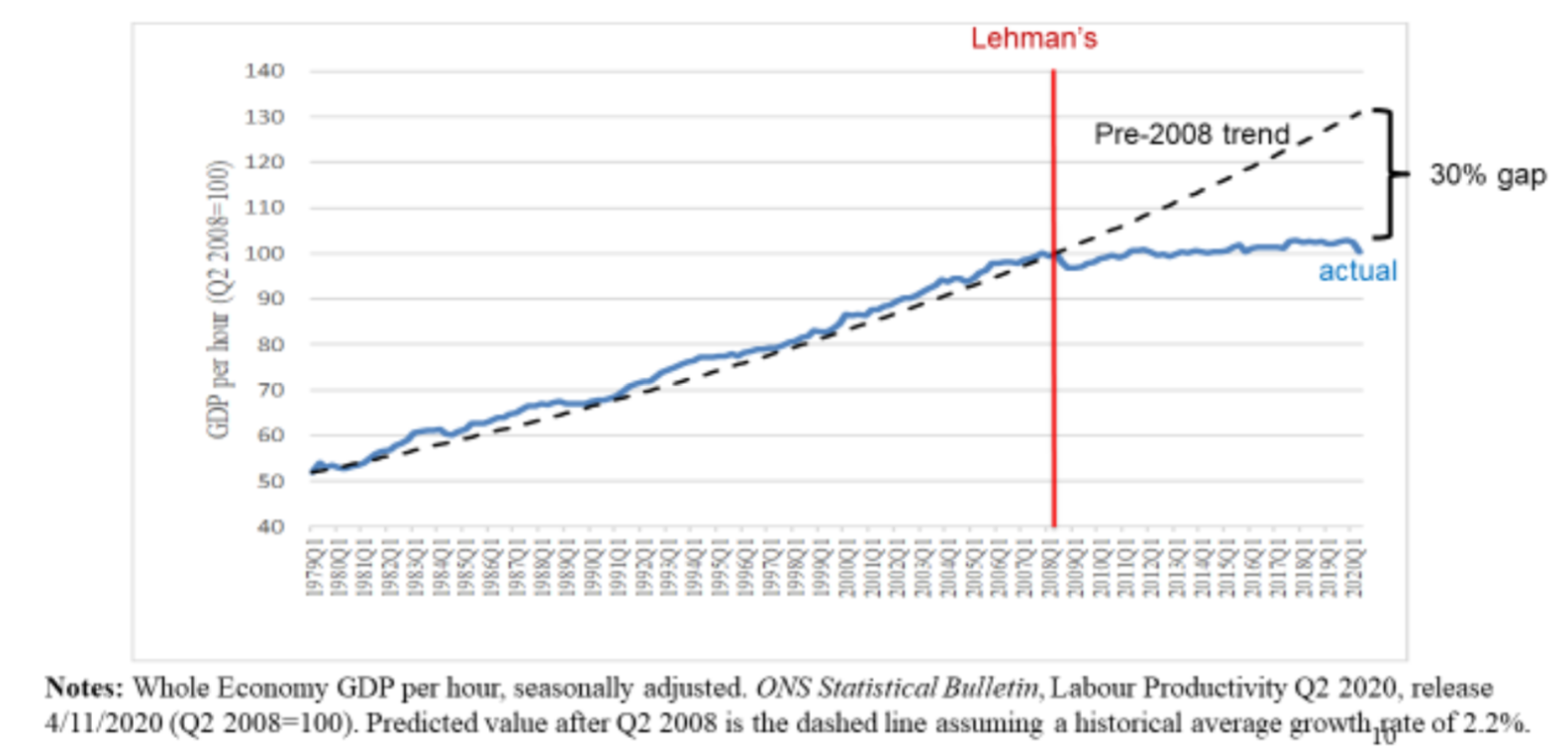

Productivity has been the number one UK economic problem since the global financial crisis in 2008. Productivity fell, recovered a bit and has then almost flatlined. There is now a 30% productivity gap between where we would have expected to be on pre-2008 trends and where we are today. Real wage growth for the mean and median worker has mirrored the stagnation of productivity. Pay stagnation is a key cause of the populist anger that helped usher in Brexit in the UK and Donald Trump in America. You cannot blame people for becoming discontented when they feel they are doing no better than their parents.

Figure 1: UK labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) 1979-2020: the disaster since the 2009-09 global financial crisis

The UK’s productivity will not be fixed by a single silver bullet, but we can see some causes. Since 1981, the UK’s investment in research and development relative to GDP has been lower than its peers. Britain’s exposure to the financial crisis played a role, as well as big cuts in infrastructure and the rapid move to austerity after the 2010 general election. Brexit has been (and will be) another factor holding back prosperity.

The case for growth

There are five main objections to the case for growth, and all of them can be rebutted.

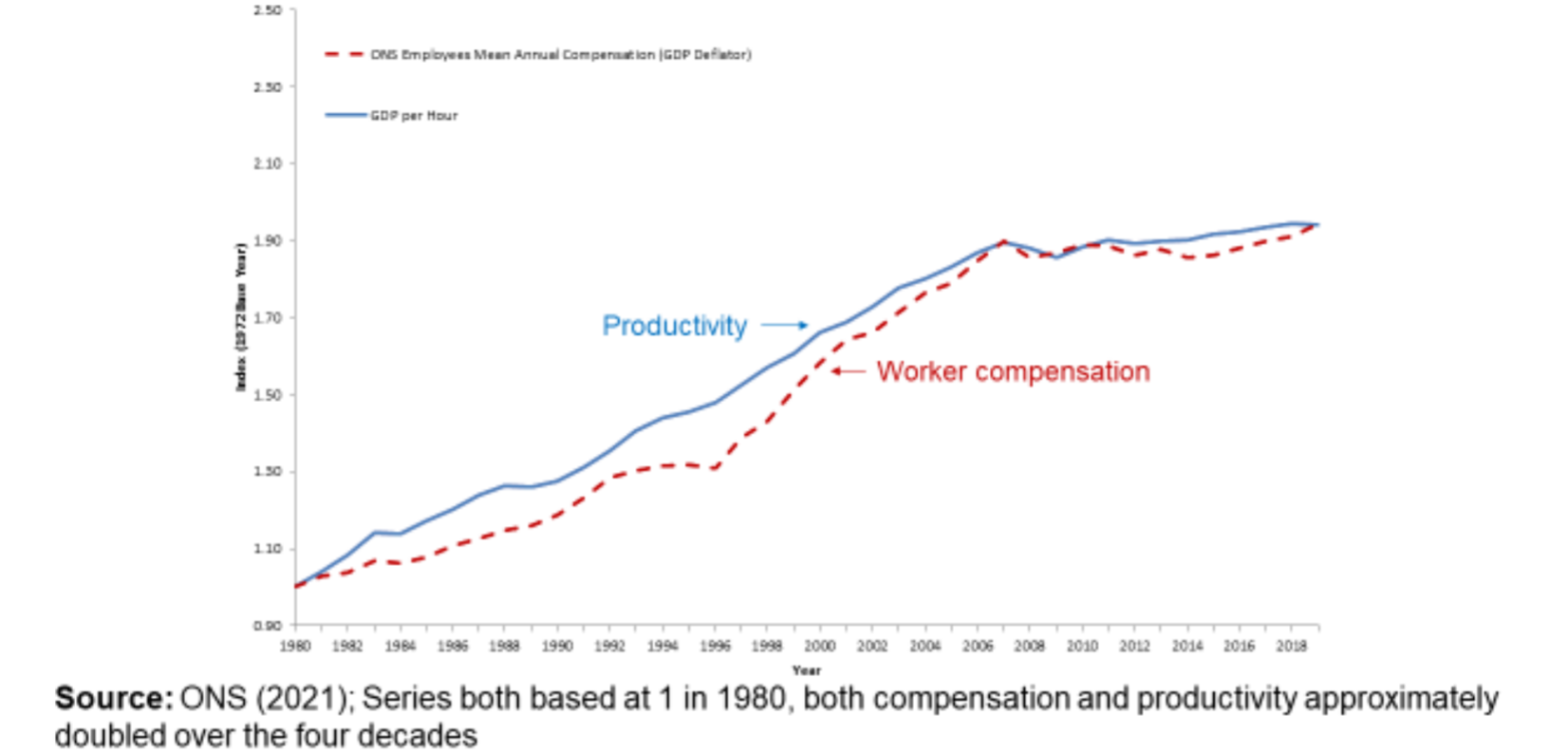

1. ‘Capitalists get all the benefit of growth, not workers’

Productivity growth goes hand in hand with faster wage growth, and that has indeed held true in the UK. Unlike the US, the share of the economic pie that workers receive has more or less stayed the same for many decades (see below). There is certainly a problem of inequality, which started rising in the early 1980s, but this is inequality between workers rather than between labour and capital.

Figure 2: UK worker average compensation tracks UK labour productivity

2. ‘Faster growth means more inequality’

The increase in inequality in many countries has not been accompanied by faster growth. In addition, it is easier to redistribute when the economic pie is growing faster.

3. ‘Growth is bad for the environment’

We need to adopt more appropriate measures of growth to incorporate the depletion of natural resources (as the 2021 Dasgupta report suggests), but tackling climate change requires green innovation. And the political will to do it weakens when times are bad.

4. ‘Growth doesn’t make us any happier’

It’s hard to measure happiness, although we’ve got better at it, and should take non-material dimensions of wellbeing seriously. But there is plenty of evidence that money makes things easier – as my Aunt Lorraine says, ‘although money doesn’t buy you happiness, it often makes your misery a lot easier to bear.’ People living in poverty tend not to be happier than the better-off.

5. ‘There’s nothing we can do to improve the growth rate’

Pessimism about growth has become the ‘new normal’ in media discourse. But there is also a growing recognition that institutions and policies can actually change the speed of growth. The LSE’s Philippe Aghion has been a pioneer of this modern growth theory, which rejects the view in traditional neoclassical economics that all we can do is adapt to fluctuations in growth rather than seeking to speed it up.

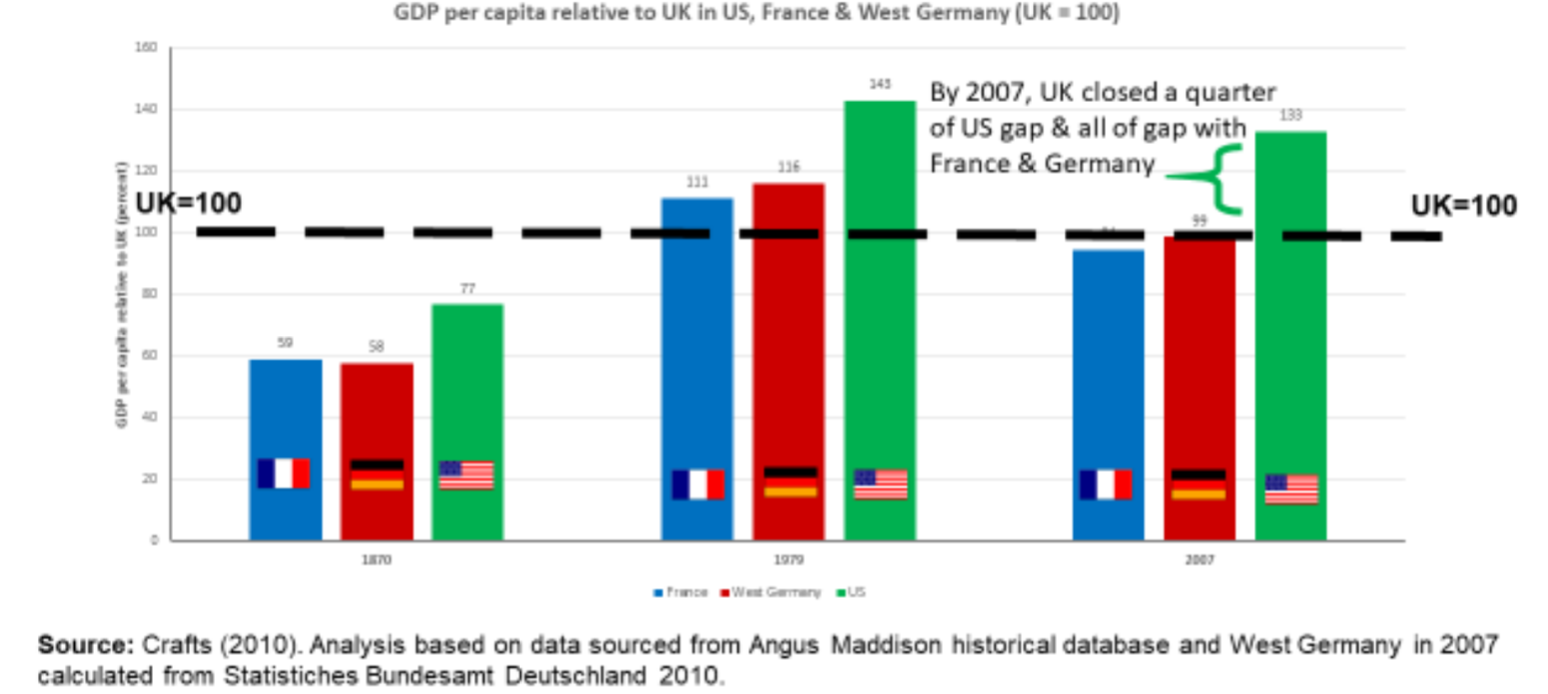

The UK experienced over a century of relative decline until the late 1970s. Between 1870 and 1970, Britain went from being a quarter richer than America to two-fifths poorer. Victorian Britain was 40% richer than France and Germany, but 11-16% poorer than our European neighbours by the end of the 1970s. Over the next three decades leading up to the 2008 crisis, a minor miracle occurred and we reversed that decline. The gap was eliminated with Europe and reduced by a quarter with the US.

This change was no accident. Policies introduced in that period played a role. There were a suite of pro-competition policies (such as EU membership, openness to foreign investment, tougher anti-monopoly laws, and reduced government subsidies for lame duck industries), more flexible labour markets, the expansion of universities, and more autonomous regulation (such as Bank of England independence).

Figure 3: After a century of relative decline, the UK closed the GDP per capita gap in the three decades leading up to the global financial crisis

The story of growth is not simply the accumulation of human and physical capital. It is fundamentally a story of technical change. Only a fifth of the growth of output per hour since the second world war is due to labour and capital – 80% is because of better technology and management practices.

Although technical change is obvious and everywhere, management is often overlooked. Innovations such as Frederick Taylor’s scientific management, Fordist mass production, Alfred Sloan’s M-form firm, Deming’s quality movement and the Toyota lean manufacturing system were all transformative. To make the biggest gains in productivity you need to make radical changes in the way you work. For example, the invention of the lightbulb took decades to feed through to productivity, because of the need to move to a factory-based system. Even today, firms can spend vast amounts on software, robots and AI, but without good management it can have little effect on the bottom line.

There are two sources of growth: innovation (such as the invention of the wheel) and diffusion (when more people use it). Innovation is harder, and to a certain extent less developed countries can rely on diffusion, but catching up gets progressively harder as the countries become richer, because there is much less headroom to grow by adapting the technologies of others when you are near the frontier.

Poor management accounts for just under half of the UK’s productivity gap with the US, and it improves when innovative firms displace incumbent firms, the phenomenon known as ‘creative destruction’. I have been working on improving measurements of management for some time as part of the World Management Survey.

A growth plan

A growth plan has a short and long run aspect that have to be joined up. A fundamental principle is that we should base innovation and the other portfolio of policies on what works – using really evidence based policy and not policy-based evidence. Here is an example of how to do this in the context of innovation policies.

In the short run, we should avoid another premature move to austerity, which would prolong depressed demand. We should take advantage of the environment of low interest rates will enable us to continue borrowing and rebuilding. We need to strike a balance between job protection and reallocation, which will mean providing incentives to move jobs between firms, and supporting start-ups, not just incumbent firms. Many of the Chancellor’s support packages are due to expire in the spring, and to avoid an even more serious recession we need to smooth that cliff-edge, and be honest about the fact that not all the government’s loans are going to be paid back. Some serious debt restructuring will be needed, such as swapping debt-for-equity and write-offs.

In the long run, we need new institutions to mitigate what I call ‘policy attention deficit disorder’ – a tendency to think short-term that has limited long-run investment, like the creation of a National Infrastructure Bank. Competition policy is due for an overhaul. Too much of it backward-looking: a merger that looks harmless today may turn out to be harmful later, such as Facebook’s purchase of WhatsApp. In the long run, we should reverse Brexit, but in the short run we should rejoin the Single Market and develop a Norway-style relationship with the EU. As the Mirlees review suggested, we should be taxing ‘bads’ like carbon emissions and relatively immobile factors like land. Building flexible markets is another priority. The CEP has proposed a Human Capital Credit that would fund people to gain intermediate skills.

Let me end with a final thought. Growth policies must think not just about stimulating the demand side for innovation through taxes and direct subsidies. We must increase the quantity and quality of the supply of the inventors and entrepreneurs of the future. For example, kids born to the richest one percent of parents are ten times more likely to grow up to be inventors than those born to the bottom 50%. My work shows that the vast majority of this relationship is not due to the lack of talent of poorer kids, but rather to the barriers they face. Policies that give children from disadvantaged groups better opportunities are not just good for equity – they will also be vital to long-run growth.

The LSE Growth Commission has set out principles for inclusive and sustainable growth, while the Centre for Economic Performance has spent three decades analysing productivity. Out recent COVID-19 analysis series has evaluated the effects of the pandemic.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It is based on Going for Growth, an LSE talk given by John van Reenen on 8 February 2021.

3 Comments