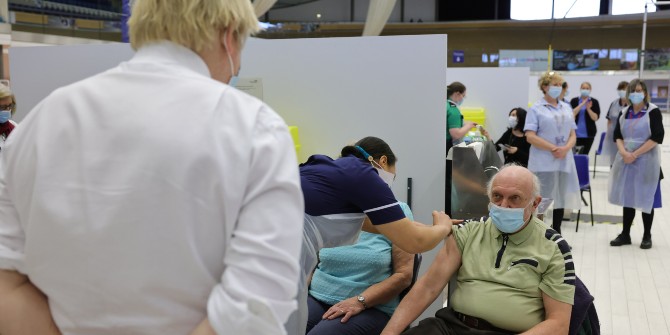

The UK’s vaccination programme has been a rare success during the pandemic. Lucy Thompson, Rebecca Forman and Elias Mossialos (LSE) explain why the NHS has been able to deliver jabs faster than any other European country.

It is fair to say that the UK government has not come off well in the pandemic. The UK’s coronavirus death toll, now over 117,000, is the highest in Europe and, relative to population size, the third highest per million population in the world. A multitude of factors have contributed to the UK’s poor performance. Some blame the delayed response to the crisis; the UK locked down later than much of western Europe, and its now infamous “world-beating” track and trace system made headlines for its slow establishment, failed uptake and security controversies. Others suggest that the UK’s fragmented society is to blame, as the huge disparities in the death toll between the rich and poor and across ethnic backgrounds highlight. Many have raised concerns over how the government’s mixed messages have created confusion and ultimately may have contributed to the rapid spread of the virus.

So it may have felt natural to assume the UK’s vaccination campaign would meet a similarly disappointing fate. But so far, it has proven an unexpected success, reaching its target to vaccinate the 15 million people in the top four priority groups by 15 February. The UK moved quicker than any other European nation to secure, approve, and deploy COVID-19 vaccines. The Pfizer-BioNTech candidate was approved in the UK on 2 December, while the EU granted approval on 21 December. Since then, the UK has added the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine (30 December) and the Moderna vaccine (8 January) to its armoury. It has also adopted a “first dose policy” to increase the flow of vaccine supply in the short term and allow for more first doses – which offer less protection than the full two-dose regime – to be delivered to more people sooner. While this met with initial concern, new and emerging data means that the same approach is now being considered by other European countries such as Germany and Denmark.

The government’s early action is praiseworthy. However, we must thank the NHS for its huge contribution and vital role in these vaccination efforts thus far. Once again, it has given us a new sense of pride and hope despite significantly reduced investment in public health in recent years. So what has supported the NHS’s success?

Unlike our European counterparts, the UK’s universal healthcare system benefits from a centralised, coordinated approach to patient care. Over 60 million patients are currently registered at GP practices in England, suggesting that over 90% of all UK residents have an NHS digital patient record. The NHS’s digital system is not far behind that of Israel, the front-runners in the global vaccination campaign statistics. Like Israel’s mandatory public health system, the NHS approach supports digital records of all patients from birth – including past hospitalisations, prescribed medications and vaccinations. This has enabled people in vulnerable groups to be identified, contacted and vaccinated as a priority. The centralised nature of the NHS also means there are whole teams in place for bulk purchasing and internal distribution. Unlike some countries now struggling to meet demand, the NHS secured resources like syringes in great enough numbers early on while vaccines were still in clinical development.

The NHS relies on a far-reaching delivery network ranging from GP surgeries, mass vaccination centres, and hospitals. It has an established ambulance taxi service, which has supported distribution supplies and coordination of vaccines to remote and rural communities. Its interpreter service and local links with religious communities mean that even those with a language barrier and those who will not be reached via standard communication channels can be reached through other mechanisms. While this does not completely dispel concerns and anxieties in groups where jab acceptance is low, overall vaccine acceptance rates remain much higher in the UK than in other countries. In the UK, NHS doctors and nurses remain the most trusted professions in England.

As well as trust, the NHS has the advantage of experience. Although never on the same scale as that now required, the NHS has successfully implemented mass vaccination campaigns in the past – the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine from 2008 and the introduction of the shingles vaccine in 2013, as well as the national flu vaccine campaigns each year, in which the UK has historically outperformed its European counterparts. These experiences undoubtedly contributed to decisions to invest in large purchases of vaccine doses early on in the development process, which ultimately bought time to sort out kinks in the supply chain so that immunisation campaigns would run smoothly.

Not only is the NHS workforce experienced in this area, but they have also demonstrated high levels of motivation and drive throughout the pandemic. Thousands of former NHS staff have gone back to the frontline to support coronavirus efforts – including the administration of vaccines. Pharmacists and physiotherapists newly trained to vaccinate are working diligently alongside nurses and physicians, and shattering antiquated hierarchies within the medical system. Large numbers of non-medical volunteers across the nation are stepping up to steward patients, assist with record keeping and dole out appointment cards.

The UK’s vaccination campaign is certainly not without flaws, and there is a long way to go before we reach the vaccination rates needed for herd immunity. As in many other countries, bottlenecks persist over vaccine supplies and the large inequities in vaccine uptake across racial and ethnic minority groups. Scientists and policymakers trying to increase uptake must develop a deeper understanding of why people are hesitant, working together with people from those communities with respect and understanding.

However, relative to the rest of the world and despite previous government blunders in the COVID-19 response effort, the UK’s vaccination rollout has been a rare pandemic success. And we can (once again) thank the NHS for much of this. It remains to be seen how the programme will shape the future of public health financing in the UK.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.