Targeting the right consumer is a key element of any successful advertising campaign. Internet platforms must show that they know who is viewing each ad. Martin C W Walker writes that, given the role individual identification plays in the internet economy, Meta and others should be paying their customers to confirm their identity rather than charging them to verify their accounts.

Meta has recently followed the example of Twitter in offering “verified” accounts to users of Facebook and Instagram for a monthly fee. Will this finally provide a way to kickstart revenue growth against Mark Zuckerberg’s social media empire or does it conflict with the fundamental economics of the web?

Over the last few years Meta has attempted a number of radical changes to its business strategy. In 2019, they announced their own digital currency called Libra. In spite of changing the business model several times and the name of their currency (to Diem), it was closed down in 2022. In 2021, Facebook rebranded itself as “Meta” and announced it was going to create an immersive virtual world, “the metaverse”. Tens of billions of dollars have been invested in the project but it has mostly succeeded in burning money and generating derision. Both for the poor quality of the graphics and the unoriginality of the concept. Simply charging for its services may seem an easier and cheaper way for Meta to generate additional revenue.

But why wait twenty years to release a premium version of a service given away for nothing? More than two decades after the start of the dotcom era, many people still struggle to understand the economics of the world wide web. An area where vast businesses have been built by giving the main product away for free. The concept of giving away software began in the 1980s with the shareware movement. Software provided as shareware can be used without any initial payment and could be freely copied and passed on to other potential users. Though the concept seemed madness, it did provide a distribution system for amateur developers and the hope that a small proportion of users would pay the creator.

At the root of shareware was a basic economic principle. With a marginal cost per copy of software close to zero, programmers did not have any risk of incurring large total costs as usage increased. Once a piece of software was written, anyone choosing to pay was a source of profit. The idea that software could, if not should, be free, became a major part of the ethos of the early Internet. Many of the early computers connecting to the Internet used free software implementations of the Internet protocols that managed communication across the net.

Early internet-based services, such as bulletin boards, chat rooms, and email were also typically provided free, generally by enthusiasts at universities or other research centres. The problem with providing software as a service as opposed to a package was tangible marginal costs per extra user. Costs that rapidly mounted as the introduction of the world wide web caused Internet usage to explode. One approach was simply to add advertising to websites providing services such as Internet search. Placing advertising on a website essentially creates a system of barter. Users of the service barter their attention and some degree of personal information in return for access to the services provided by the website.

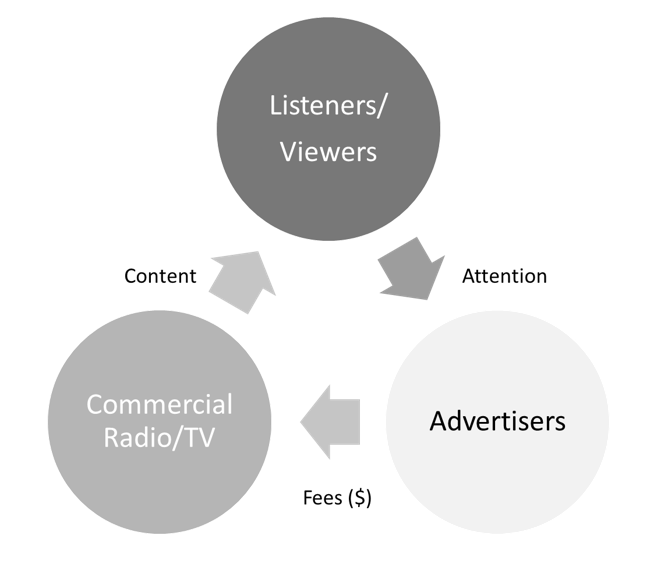

The idea of a three-way relationship between providers of a free service, advertisers and users of a service is not remotely new. It was the foundation of the business model of commercial radio from the 1920s and commercial television from the late 1940s.

Figure 1. Three-way relationship between providers of a free service, advertisers, and users

The early dot.com platforms had to re-learn the lessons of the radio and television. Simply providing a new medium for advertising was no guarantee of profits. Winning a greater share of advertising revenues comes from being able to identify who was viewing adverts. Giving advertisers the ability to focus their ads on those most likely to buy their products. There is little value in advertising cat food to dog lovers or beer to teetotallers.

Estimation of viewing figures for TV programmes and later the specific demographics of audiences was started by ACNielsen in 1950, only a few years after the start of commercial television in the United States. Sample audiences were paid to provide information on their viewing, initially via written diaries and later electronic means. The ability to create targeted advertising clearly had value to advertisers, rating agencies and TV companies.

Google was one of the pioneers of targeted Internet advertising. The company was loss-making from its inception in 1996 until 2001. The sudden switch to profitability in 2001 was driven by the introduction of “AdWords” in October 2000. AdWords displayed advertisements relevant to the user’s search term and whatever other information Google could extract from the user via the usage of “cookies” and analysis of users’ IP addresses (all devices accessing the Internet have a unique IP address that provides basic information such as the general location of the user).

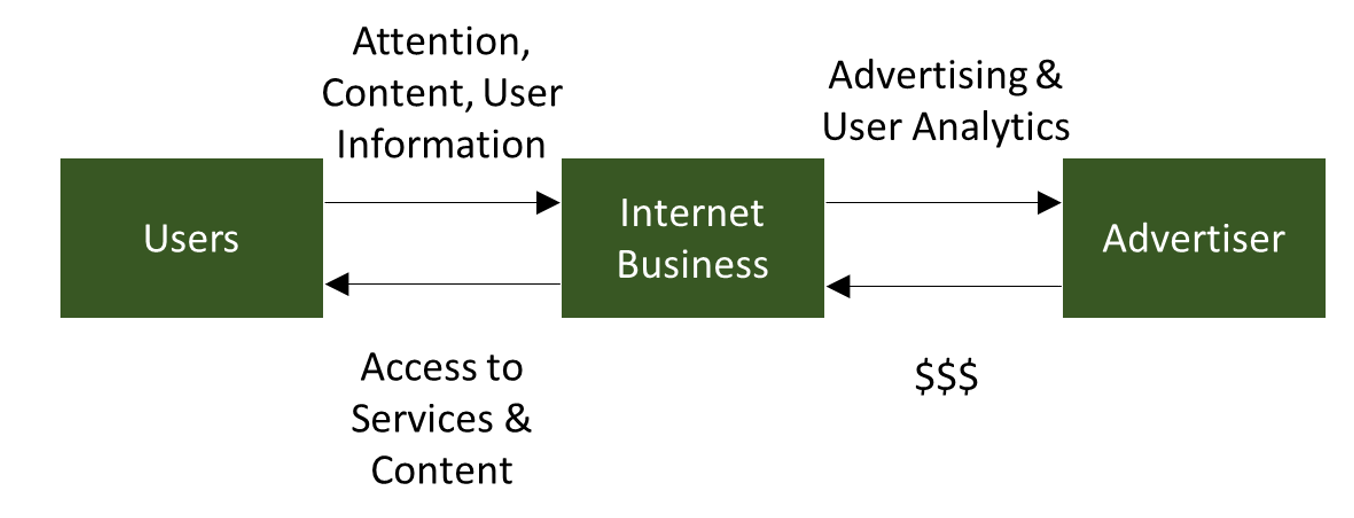

Social media, as opposed to “free” email or search facilities, added another twist to the barter model. Users were the primary creators of content that was in turn consumed by other users. Which gives us Facebook’s fundamental business model.

Figure 2. In social media, users act as both creators and consumers of content

The challenge for firms relying on this model (and for services that do not explicitly involve the creation of content like search engines) is that the firms do not have verified, uniquely identified users. They may know a user is an individual (mostly) if they are forced to create an account. They have a good idea a specific user account is of a given gender, likes cats, probably lives in a particular city and is likely to be in a relationship with the owner of the account called “FurryFeet1492”. However, without a full name, address and date and birth, they cannot cross-reference their data against other data sources including electoral registers, credit ratings. They cannot even be sure that their statistical inferences about their customers are true. Let alone confirm the carefully focused advertisement with cute kittens really persuaded FurryFeet1492 to try a new brand of cat food.

Nirvana for a technology firm is knowing who their customers are for certain. This is something achieved by the large internet retailers such as Amazon. They know many of their users’ key details including their bank details and addresses as well as what they actually purchased. This is one of the reasons Amazon’s revenues from advertising have grown over 2,200% since 2015. Though the total of $37.4 billion (Amazon annual report, p. 66) is considerably smaller than Meta’s $113 billion, Meta’s revenues are in decline.

The economic reality is that Meta should be paying their customers to confirm their identity rather than charging them.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Solen Feyissa on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.