Professional, social, legal and institutional controls lag almost a decade behind accelerating artificial intelligence. Leslie Willcocks writes that such lack of ethical and social responsibility puts us all in peril and it is time to start issuing serious digital health warnings to accompany the technology. He describes the Artificial Imperfections (AI) Test, which he created to guide practical and ethical use of AI.

With this big current idea of artificial intelligence (AI), we seek to make computers do the sorts of things only minds can. Some of these activities, such as reasoning, are normally described as “intelligent”, while others, such as vision, are not. Unfortunately, as you can experience from its latest manifestation, ChatGPT, AI is so over-hyped with fantasies of power that, with its publicity machine, it’s not just the pigs that are flying, it’s the whole farm.

The term “artificial intelligence” itself is misleading. At present, it nowhere equates with human intelligence. At best it refers to the use of machine learning, algorithms, large data sets, and traditional statistical reasoning driven by prodigious computing power and memory. It is in this sense that I will use the term here. The media and businesses subsume a lot of other lesser technologies under “AI”. It’s a nice shorthand and suggests that a lot more is going on than is the case.

Stepping back, we need a better steer on what the limitations of AI are. As a counterweight, I am going to look at how these technologies come with in-built serious practical and ethical challenges. To start off, here are three things you need to bear in mind:

- AI is not born perfect. These machines are programmed by humans (and possibly machines) that do not know what their software and algorithms do NOT cover, cannot understand the massive data being used, ignore biases, accuracy and meaning issues, do not understand their output, and cannot anticipate the contexts in which the products are used, nor the likely impacts.

- AI is not human and never will be, despite all our attempts to persuade ourselves otherwise. Neuroscience shows that the “brain like a computer, computer like a brain” metaphor is a thin and misleading simplification. Our language tricks us into saying AI is intelligent, feels, creates, empathises, thinks, and understands. It does not and will not, because AI is not alive, and does not experience embodied cognition. Meredith Broussard, in her book Artificial Unintelligence, summed this up neatly: If it’s intelligent it’s not artificial, if it’s artificial, it’s not intelligent.

- As today’s ChatGPT examples illustrate, the wider its impact, the more AI creates large ethical and social responsibility challenges.

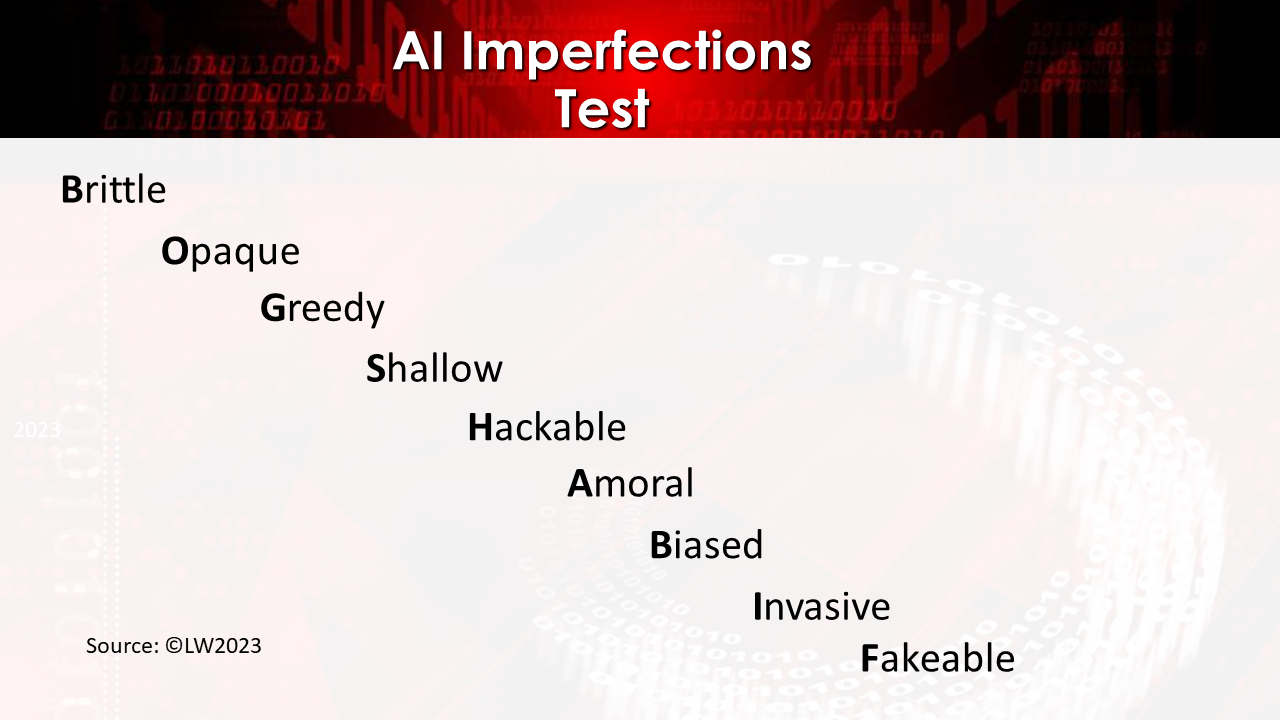

In preparing a new book, Globalization, Automation and Work: Prospects and Challenges, I have created what I am calling an Artificial Imperfections (AI) Test to guide practical and ethical use of these technologies. There are nine benchmark points in this test (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Artificial Imperfection Test

Let’s look at these one by one:

Brittle. This means that AI tends to be good at one or two things rather than, for example, the considerable flexibility/dexterity of humans and their skills. You will hear plenty of examples of what AI cannot do. To quote the Moravec paradox (Moravec 1988):

“…it is comparatively easy to make computers exhibit adult level performance on intelligence tests or playing checkers, and difficult or impossible to give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception and mobility”.

ChatGPT is very attractive because it is unusually adept and widely applicable, due to its fundamental natural language model and the vast data lake it has established and continually updates.

Opaque. AI is a technology ‘black box’ and it is not clear how it works, how decisions are made and how far its judgements and recommendations can be understood and relied upon. A lot of people are working on how to counter the intangibility and lack of transparency that comes with AI. They also have to wrestle with the immense data loads and the speed at which AI operates, much of it beyond human understanding. In such a hard-to-identify world, small errors can accumulate to massive misunderstandings. ChatGPT is an open field for these problems

Greedy. AI requires large data training sets and thereafter is set up to deal with massive amounts of variable data. Processing power and memory race to keep up. The problem is that a great deal of data is not fit for purpose. And bad data can create misleading algorithms and results. The idea that very big samples solve the problem (what is called big data, as used in ChatGPT) is quite a naïve view of the statistics involved. It is not really possible to correct for bad data. And the dirty secret is that most data is dirty.

Shallow. AI skims the surface of data. As said earlier, it does not understand, feel, empathise, learn, see, create or even learn in any human sense of these terms. Michael Polanyi is credited with what has become known as the Polanyi Paradox: people know more than they can tell. Humans have a lot of tacit knowing that is not easily articulated. With AI there is actually a Reverse Polanyi Paradox: AI tells more than it knows, or rather, more accurately, what it does not know.

Hackable. AI is eminently hackable. It does not help that well-funded state organisations are often doing the hacking. Online bad actors abound. The global cybersecurity market continues to soar, reaching some $US 200 billion by 2023 with a 12% compound annual growth rate thereafter. Of course AI can be used to support but also hack cybersecurity.

Amoral. AI has no moral compass, except what the designer encodes in the software. And designers tend not to be specialists in ethics or unanticipated outcomes.

Biased. Every day there are further examples of how biased AI can be, including ChatGPT and similar systems. Biases are inherent in the data collected, in the algorithms that process the data, and in the outputs in terms of decisions and recommendations. The maths, quants and complex technology throw a thin veil of seeming objectivity over discriminations that are often misleading (such as in predictions of future acts of crime) and can be used for good or ill.

Invasive. Shoshana Zuboff leads the charge on AI invasiveness with her recent claim that ‘privacy has been extinguished. It is now a zombie’. AI, amongst many other things, is contributing to that outcome.

Fakeable. We have also seen plenty of illustrative examples of successful faking. Indeed, with a positive spin, there is a whole industry devoted to this called augmented reality.

Looking across these challenges and AI’s likely impacts, you can see that technologies like Chat GPT contain enough practical and ethical dilemmas to fill a textbook. New technologies historically tend to have a duality of impacts, simultaneously positive and negative, beneficial and dangerous.

With emerging technologies like AI and ChatGPT we have to keep asking the question, “does ‘can’ translate into ‘should’?” In trying to answer this question, Neil Postman suggested many years ago the complex dilemmas new technologies throw up. We always pay a price for technology. The greater the technology, the higher the price. There are always winners and losers, and the winners always try to persuade the losers that they are winners. There are always epistemological, political and social prejudices imbedded in great technologies. Great technologies (like AI) are not additive but ecological: they can change everything. Technology can become perceived as part of the natural order of things, therefore controlling more of our lives than may be good for us. These wise warnings were given in 1998 and have even more urgency today.

My own conclusion, or fear, is that collectively our responses to AI display an ethical casualness and lack of social responsibility that put us all in peril. Once again professional, social, legal and institutional controls lag almost a decade behind where accelerating technologies are taking us. It is time, I think, to start issuing serious digital health warnings to accompany these machines.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Jonathan Kemper on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.