Many central banks are considering issuing central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which can be used for retail payments. One concern is that CBDC may compete with banks in providing payment balances and services, potentially leading to a reduction in deposit and credit creation — in other words, disintermediation. Jonathan Chiu, Seyed Mohammadreza Davoodalhosseini, Janet Jiang and Yu Zhu find that a CBDC might not lead to disintermediation if banks have market power in the deposit market.

In our model for a recent research article (Chiu et al. 2023), banks issue deposits to households and extend loans to entrepreneurs. Households use deposits to pay for consumption goods. The central bank, in addition, issues two payment instruments: cash and CBDC. Some transactions require cash as the sole payment method, such as those in an offline setting. In other settings, only deposits can be used, such as online transactions. There are also transactions where all payment instruments are accepted, such as those in brick-and-mortar stores. We focus on a deposit-like CBDC that is a perfect substitute to deposits in terms of payment functions and receives an interest rate set by the central bank.

Our model highlights the importance of the market structure of banking. When banks have market power in the deposit market, issuing a CBDC can promote bank intermediation. With market power, banks limit the supply of deposits to keep the deposit rate below the competitive level. As an outside option for depositors, the CBDC introduces an interest rate floor for bank deposits and decreases the incentive of commercial banks to restrict their deposit supply.

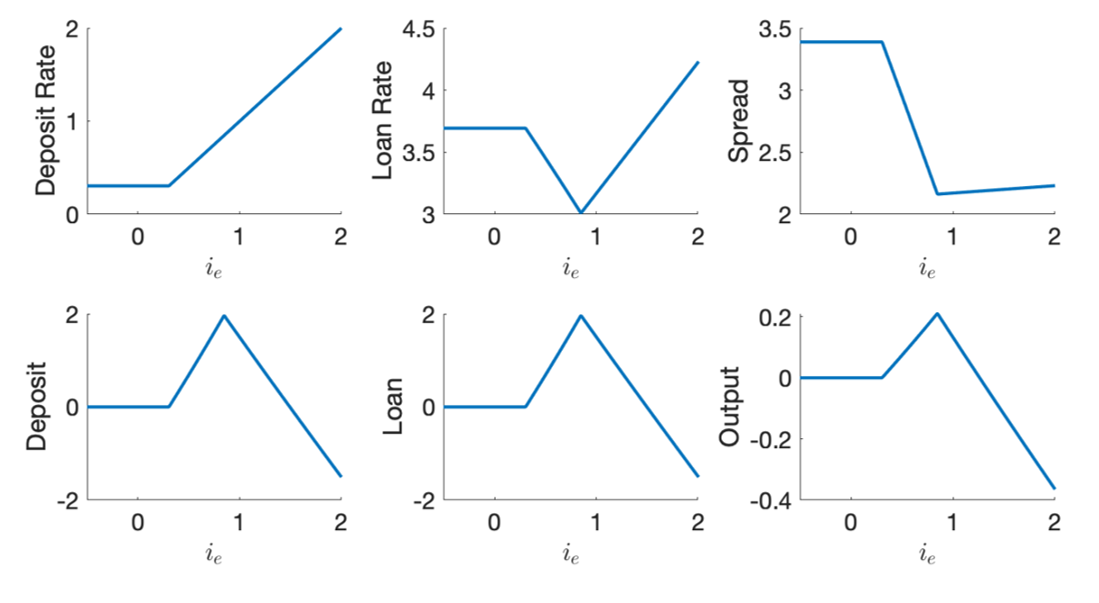

Figure 1. Effects of the interest rate on CBDC

Source: Chiu et al. (2023)

Figure 1 demonstrates the impact of the CBDC interest rate (i_e) on the deposit rate, loan rate, and their difference (presented in the top panels), as well as the percentage changes in deposits, loans, and overall output compared with the equilibrium without a CBDC (shown in the bottom panels). When the CBDC rate is lower than the deposit interest rate without a CBDC (represented by the horizontal segments in the graphs), there are no consequences for the equilibrium rates and quantities. When the CBDC rate surpasses this level, the economy enters a second region. Banks match their deposit rates with the CBDC rate, which attracts more deposits. As long as the banks’ profit margin remains positive, they will use the extra deposits to finance additional loans, which lowers the loan interest rate and the spread. More loans lead to higher output. Note that in this region, the CBDC has a zero market share; rather, its mere existence as an outside option for households disciplines banks and expands deposits, loans, and output. Finally, when the CBDC rate is too high, banks’ profit margin becomes zero and the expansion stops. Any further increase in the CBDC rate will compel banks to raise the loan interest rate to break even, which leads to a decline in deposits, loans, and output.

As the economy becomes cashless…

Many central banks are reluctant to pay positive interest on their digital currencies. How does a non-interest-bearing CBDC affect the economy? We show that as the use of cash in transactions declines over time, consumers rely more on deposits, giving banks more market power. This could result in higher banking fees, lower interest rates on deposits or poorer quality bank services. In this case, a non-interest-bearing CBDC can create competitive pressure, motivating banks to provide better terms and services and expanding intermediation.

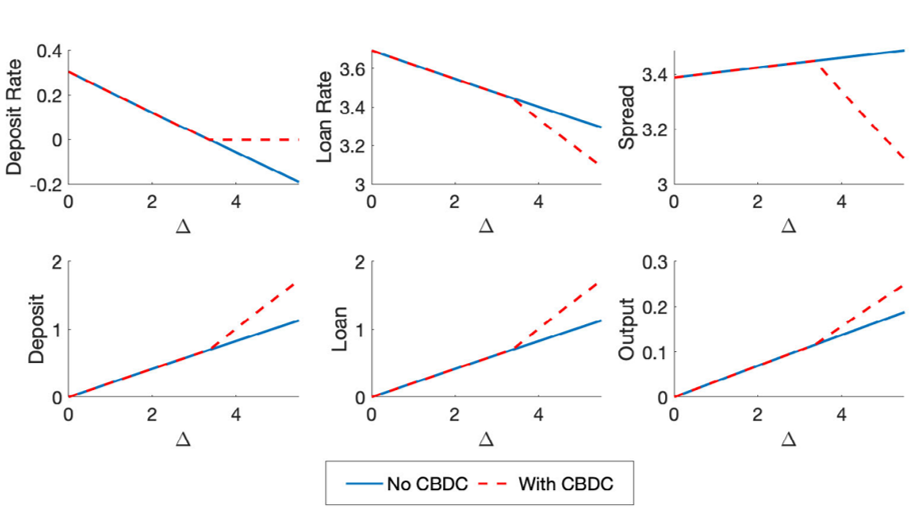

We incorporate the idea of the economy going cashless by assuming that a fraction Δ of sellers who used to accept both cash and deposits stop accepting cash. One interpretation is that some physical retailers have transitioned to selling solely online and can no longer accept physical cash. We compare the equilibrium outcomes with and without a CBDC as Δ rises. The results without a CBDC are denoted by the solid blue lines in Figure 2. As Δ increases, banks gain more market power because deposits become a more desirable payment instrument. As a result, banks lower the interest rate on deposits, but depositors will still hold more deposits. If Δ is sufficiently high, the deposit rate can be negative without a CBDC, that is, banks charge fees on deposits. The dashed red curves represent an economy with a non-interest-bearing CBDC. In this case, the CBDC sets a floor at zero for the deposit interest rate, which leads to more deposits, more loans, and higher output.

Figure 2. Effects of a non-interest-bearing CBDC as the economy becomes cashless

Source: Chiu et al. (2023)

Related literature

The economic literature on CBDCs is growing fast. Chapman et al. (2023) provide a comprehensive literature review of the effects of CBDC on banking. Keister and Sanches (2023) and Andolfatto (2021) address the disintermediation question with different market structures. Chiu and Davoodalhosseini (2021) show that an interest-bearing CBDC could improve bank intermediation even when banks do not have market power. The reason is that a CBDC, by paying interest to consumers, could raise their demand for goods from firms which, in turn, borrow more loans to support the production of these goods.

Whited, Wu, and Xiao (2022) incorporate alternative fundings sources such as wholesale funding. They find that for every $1 captured by a non-interest bearing CBDC, deposits decrease by $0.7-$0.8, while lending decreases by a smaller amount due to banks’ ability to replace lost deposits with costly wholesale funding. However, increased dependence on the latter raises the risk of banks default. Monnet et al. (2021) explore a model in which an interest-bearing CBDC competes with bank deposits backed by risky lending. Increasing the CBDC’s interest rate drives banks to raise deposit rates, expanding lending and improving monitoring. In other words, the CBDC acts as a disciplining device for banks to offer safer deposits. Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019) show that central banks can avoid crowding out bank lending if they lend to commercial banks under certain conditions. In particular, the central bank can swap private liquid assets with public liquid assets, keeping the liquidity constraints of banks and households unaffected. While this “equivalence result” establishes conditions under which issuing a CBDC does not matter, much ongoing research aim to study implications when this equivalence does not hold.

* The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and may differ from official Bank of Canada views.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Bank Market Power and Central Bank Digital Currency: Theory and Quantitative Assessment, Journal of Political Economy.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by David Dvořáček on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

It helps if the CBDC issuer owns all the banks, sits on every board, and is run by the world’s smartest, most successful financiers.

Expect the first 21st century city, currently called Xiong’An New Area, to go 100% digital, with CBDCs front and center.

The new international reserve currency, under construction since 2009, will be a CBDC for central banks.