The interconnected nature of the financial system has been at the centre of post-crisis regulation discussions among academics and policymakers. Levent Altinoglu and Joseph Stiglitz write about their work to help explain the structure of the financial system, its consequences for risk-taking and systemic risk, and how policy can help address it.

The financial systems of advanced economies are typically highly interconnected, with a few large financial institutions playing a predominant role and interacting with many smaller institutions through various financial markets, such as derivatives, insurance, equity, syndicated loan, deposit, or money markets. While this structure, sometimes referred to as core-periphery, may help buffer small shocks, it is a source of systemic instability as it concentrates resources in systemically important banks, leaving the rest of the system vulnerable to their failure. But what leads such a structure to arise in the first place? Why do financial institutions concentrate risk in a manner that generates systemic instability, rather than spreading risk across the financial system?

In a recent paper (Altinoglu and Stiglitz, 2023), we propose a theory to jointly explain the structure of the financial system and show how it alters the risk-taking incentives of financial institutions. According to the theory, by issuing financial claims on the interbank market, risky institutions endogenously become too interconnected to fail from the perspective of the government, which optimally (that is, given the financial structure) intervenes during crises. This concentrated structure of the financial system enables institutions to share the risk of systemic crises in a privately optimal way but leads to excessive risk-taking from a social perspective, even by peripheral institutions. As a result, interconnectedness and excessive risk-taking reinforce one another — a dynamic which exacerbates systemic risk. The theory implies that macroprudential regulation that limits the interconnectedness of risky institutions can improve social welfare.

A theory to explain the interconnected financial structure

The model we construct is parsimonious and features two key ingredients: a government which lacks commitment (in particular, the commitment not to intervene, if ex post it turns out that intervention is welfare increasing) and an interbank market through which financial institutions can freely engage in financial contracts. Banks can invest either in risky investments or prudent investments, and they finance these investments through deposits and by borrowing from one another in the interbank market. The network structure of the interbank market is determined in the model by the lending relationships that form as a result of banks’ decisions. When banks are heavily exposed to risky investments, there are socially costly fire sales in bad states of the world which we refer to as a crisis. The key property of our model is that bank risk-taking affects the structure of the interbank market, and vice versa. They are both endogenous and have to be “solved for” simultaneously. The core-periphery structure of the interbank market emerges as the result of incentives of banks to jointly take high levels of risk, and itself sustains such risk-taking in equilibrium.

Two main insights emerge from our model. The first insight is that the concentrated structure that emerges in equilibrium enables financial institutions to share the risk of systemic crisis in a privately optimal way, that is, in a way that enhances the value of the bailouts. When a bank holds a risky asset, it bears crisis risk – the risk of incurring a loss during a crisis – precisely when banks value returns the most. Banks are unwilling to hold excessively risky assets in the absence of some form of insurance against this risk.

The core-periphery structure of the interbank market plays a crucial role in providing banks precisely this kind of insurance against the risk of crises, thereby making it optimal for banks to hold risky assets in the first place. This happens because during a crisis, the government optimally bails out any bank which is sufficiently large or interconnected (a systemically important bank) to prevent the fire sales associated with their failure. During a crisis, these systemically important banks forgo some of the bailout funds they receive from the government to pay their interbank claimholders a higher rate of return than what they earn on their own assets. Effectively, these contingent payments insure claimholders against losses from the systemically important banks’ investments during crises.

Thus, interconnected systemically important banks arise in equilibrium because they are the only private agents able to issue liabilities that maintain their value during a crisis, precisely because these banks’ liabilities are implicitly guaranteed by the government. Risk sharing between these systemically important banks and non-systemic banks generates a core-periphery structure in financial markets. Ironically, it is the government’s attempt to reduce moral hazard by only bailing out systemically important banks that gives rise to the core-periphery structure, which, we show, itself gives rise to systemic moral hazard.

Excessive risk-taking and interconnectedness

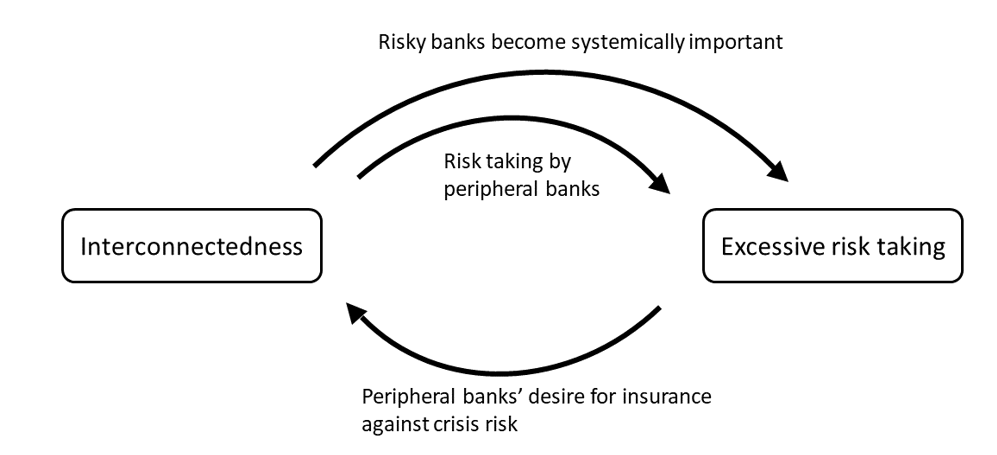

The second key insight which emerges from the model is that excessive risk-taking and interconnectedness reinforce each other. This adverse feedback loop arises in the model due to three channels, each of which is new to the literature. Figure 1 shows a stylised representation of this two-way interaction.

Figure 1. Excessive risk-taking and interconnectedness reinforce each other

The first channel through which interconnectedness alters risk-taking is represented by the top arrow in Figure 1. Since downside risk is implicitly insured by the government, the interbank market channels funds to investment opportunities with high upside risk. As a result, the institutions which end up becoming large and interconnected (that is, systemically important banks) are precisely those with relatively risky portfolios.

The second channel, represented by the middle arrow in Figure 1, is that the implicit insurance offered by a systemically important bank’s liabilities enables smaller, peripheral institutions to hold excessively risky assets, even though they do not directly benefit from bailouts themselves. This channel causes the resources of smaller, peripheral banks to be concentrated in excessively risky projects, magnifying the aggregate exposure of the economy to excessive risks. Through these two channels, interconnectedness may lead to widespread excessive risk-taking, increasing the risk of crisis.

In turn, crisis risk reinforces interconnectedness as a result of interbank risk sharing, represented by the bottom arrow in Figure 1. To obtain insurance against crisis risk, smaller, non-systemic institutions in the periphery invest in the liabilities of systemically important banks since they are implicitly insured by the government.

Taken together, these three channels of risk-taking and risk sharing imply that interconnectedness and excessive risk-taking reinforce one another – a dynamic that exacerbates systemic risk and has implications for the design of optimal policy.

How policy can mitigate the risks

In our setting interconnectedness leads to inefficiencies when it concentrates risk and alters risk-taking behaviour beforehand, rather than simply by propagating a shock across banks through domino or cascade effects. As a result, interconnectedness warrants policy intervention when some institutions are too interconnected to fail, and when these institutions engage in risky activities (which itself is induced by interconnectedness). Therefore, the inefficiencies associated with interconnectedness identified in this paper could appropriately be defined as a too-interconnected-to-fail problem (as opposed to the too-many-to-fail problem of Acharya and Yorulmazer, 2007).

We show that optimal macroprudential policy discourages interbank lending to institutions with risky portfolios and can be implemented with restrictions on loans to banks with risky portfolios and to banks with direct or indirect exposures to other risky banks. In contrast, policies that only reduce leverage are inadequate in dealing with the problems that we have identified here, since these inefficiencies derive from the asset side of bank balance sheets and do not depend on banks’ capital structure per se. We thus provide a rationale for some post-crisis regulations designed to reduce interconnectedness, but those adopted so far may be inadequate in important respects.

Authors’ disclaimer: The views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, nor any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System.

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Collective Moral Hazard and the Interbank Market, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. A version of this post appeared on VoxEU.

- The post represents the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by David Vincent on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.