UK homes must be retrofitted to become energy efficient and carbon neutral. However, retrofitting the UK’s housing stock is a “mammoth task” since most emissions reductions need to be achieved between the late 2020s and early to mid-2030s. Jamie Morgan writes that framing retrofitting as an individual’s investment decision is reckless in times of uncertainty, squeezed incomes and low confidence. He says the government must provide massive and accelerated financing.

In its latest report to parliament the CCC states that the UK is increasingly likely to miss its emissions reduction targets. To achieve a 68% reduction on 1990 levels by 2030, the rate of reduction must almost quadruple. A central problem remains decarbonisation of the housing stock. Carbon emissions related to buildings remain stubbornly high and are around a fifth of UK annual emissions, of which the vast majority derives from homes. In a 2019 report, the CCC was quite clear, “We will not meet our targets for emissions reduction without near complete decarbonisation of the housing stock”. It is not an optional extra. There are approximately 28 million homes in the UK, nearly two fifths built before 1946 and over half before the 1965 Building Regulation first required thermal insulation. The ultimate aim is to generate energy-efficient, carbon neutral and climate resilient housing, but the UK housing stock is very far from this. Using the standard EPC energy efficiency rating, for example, only around 40 per cent of housing is rated C (energy efficient) or higher and the vast majority have gas heating systems. Many are, therefore, not yet sufficiently insulated to be compatible with the technologies which, it is anticipated, will provide heating/cooling in the future, especially heat pumps.

How to decarbonise UK homes

In any case, most of the housing stock that must contribute to radical decarbonisation has already been built. This is why retrofitting is needed and this has two parallel aims: a) improve energy (heating/cooling) efficiency, bringing homes up to some designated standard; and b) substitute low/no carbon alternatives for emissions-producing or -dependent heating/cooling systems and appliance technologies.

This is to be achieved via some combination of:

- The roof space, exterior and interior walls and floor might be insulated to maintain a consistent interior temperature and/or reduce heat loss.

- Windows may be swapped for double or triple glazed units and tinted or electrochromic glass (capable of changing colour in response to conditions) may be fitted.

- Draft exclusion may be applied to doors and other gaps (possibly in combination with modifications to enhance capacity to create air flow to the exterior for “passive cooling”).

- In conjunction with a broader process of “electrification”, oil heating, coal fires and natural gas boilers may be swapped for newly installed low carbon heating/cooling systems (solar, micro-wind, heat pumps, green hydrogen etc.), hot water tanks may be insulated, and, if relevant, battery storage may be fitted for any electricity generated.

- Smart environmental control technologies may be installed for micro-environmental management and efficiency optimisation (smart meters, advanced thermostats, thermostatic valves, and perhaps, ultimately, AI supported management systems).

The gold standard for effective retrofitting is what is termed a “whole house” approach, and this simply means ensuring that modifications are undertaken in an appropriate order and with a view to suitability and compatibility. This implies project management from a suitably trained person who is in charge of a team with specialised skills and training. In most cases this necessitates a “fabric first” approach, which targets insulation etc. to provide the energy efficiency required for new heating/cooling technologies, as previously noted.

A “mammoth task”

It should be dawning on you by this point that retrofitting some significant proportion of 28 million homes is a mammoth task. This is especially so given that the overall aim of achieving net zero (and this is already a disputed target) through the CCC carbon budgets anticipates that changes in all sectors of economy and society must begin more or less immediately and the vast majority of emissions reductions need to be achieved in the late 2020s and early to mid-2030s. The Sixth Carbon Budget, published in 2020, suggests that within a “balanced pathway”, loft insulation needs to accelerate from the 27,000 undertaken in 2019 to more than 700,000 per year by 2025, while cavity wall insulation needs to increase from 41,000 to more than 200,000 per year, again by 2025. By 2035 at the latest, (almost) all homes are expected to be rated C or higher in the energy performance certificate (EPC) and heat pump installation is assumed to grow to around one million installations per year by 2030.

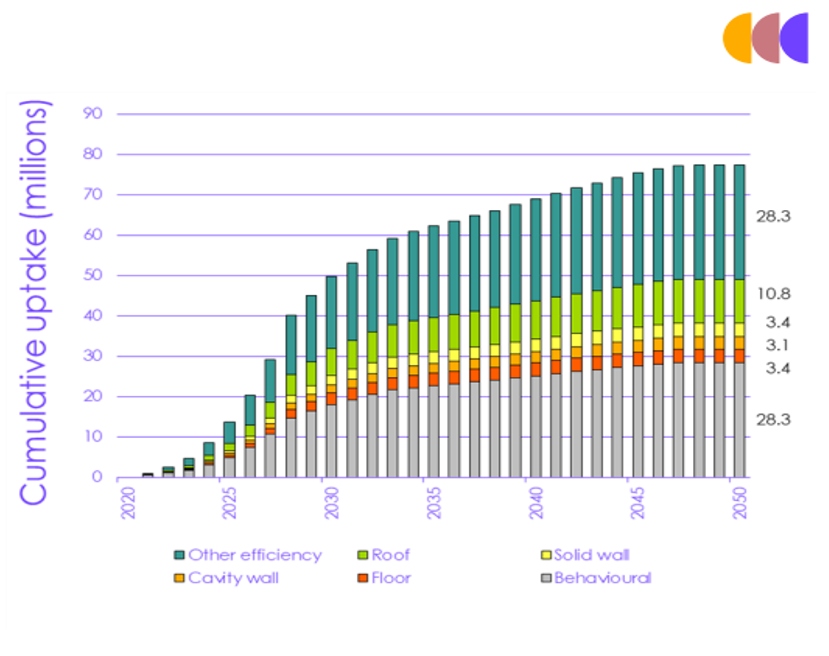

Figure 1a. Uptake of heating efficiency measures in existing homes

LSEBR Note: This figure is reproduced from this report by the Climate Change Committee, under CCC copyright terms and conditions. CCC Notes: This does not include measures which save other electrical demand such as LEDs, wet and cold appliances. Behavioural measures include multi-zonal heating controls and pre-heating (i.e., turning heating on early, off-peak). Source: element Energy for the CCC (2020) “Development of trajectories for residential heat decarbonisation to inform the sixth carbon budget”.

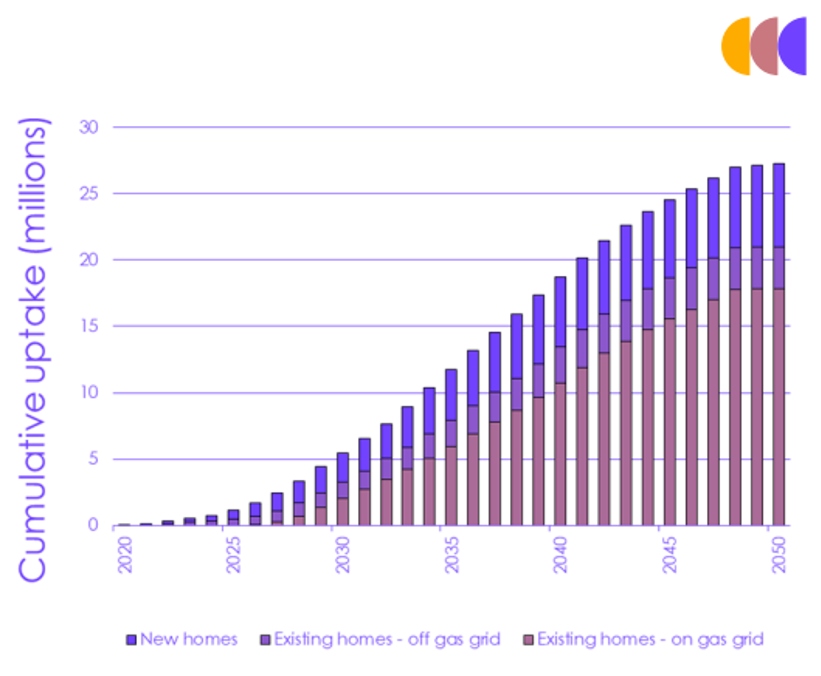

Figure 1b. Uptake of heat pumps in residential buildings

LSEBR Note: This figure is reproduced from this report by the Climate Change Committee, under CCC copyright terms and conditions. Source: element Energy for the CCC (2020) “Development of trajectories for residential heat decarbonisation to inform the sixth carbon budget”.

The role of government

To be clear, there is progress on relevant technologies, but there is as yet little in the way of long-term planning and financing for retrofitting itself. Government has adopted a “building a market” approach. This essentially means that Government sees its role as twofold. First, to facilitate private sector development of the skills base and supply chain needed to provide modifications and technologies. Second, some degree of inducement to householders to undertake required retrofitting etc. Examples include communication campaigns to make households aware of relevant timelines and some degree of incentives, financing options etc. to encourage them to make those changes. Such incentives currently include a grant of £5,000-£6,000 towards the cost of installation of an air or ground-source heat pump or biomass boiler.

In its 2022 report to Parliament on progress towards achieving carbon budgets the CCC recently scored buildings as an overall yellow (green denotes “credible plans”, yellow “some risks”, orange “significant risks” and red “insufficient plans”). The report makes 38 recommendations on “policy gaps”. The latest report confirms this picture and there has also been no shortage of criticism of government policy in recent years, for example, from the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, from the Resolution Foundation, the Green Alliance, the Skidmore Report and others.

Who finances it

There is a more fundamental issue, though: rather than collective or community-focussed climate emergency planning, retrofitting has been framed as a problem for an individual economic agent engaged in a rational calculation regarding costs and benefits of a financial decision (an investment in property). Arguably, framing retrofitting as an individualised investment decision and thus locating retrofitting policy within the vagaries of affordability in uncertain times is reckless. Incomes are constrained, confidence is low, expectations of the future are negative and uncertainty is high. This situation does not seem set to turn merely because inflation reduces (if it in fact it does so). The dilemma is clear, “I can’t afford to do this thing we can’t afford not to do”. As readers must surely be aware, steadily rising interest rates can only exacerbate this problem.

Many commentators are now suggesting that the UK is in the early throes of what may be its worst housing market crash in decades. The Office for National Statistics calculates a measure of housing affordability and in March 2023 reported a ratio of 8.3 between typical annual full-time employed earnings and average house prices. By some measures house prices have not been as high as they are now against incomes since 1880.

There is, of course, a bigger picture here. Climate emergency is a global issue and so is finance. Finance is a multi-faceted issue. Articles 8 (loss and damage) and 9 (the finance mechanism) of the Paris Agreement recognise that climate change has costs and that those most vulnerable to consequences have done the least to cause our current predicament. As this year’s Paris Summit for a New Global Financing Pact makes clear, there is a huge gap between what is needed and what is currently conceived in order to make necessary changes. At the same time, 21st century industrial strategies built around green infrastructure and investment have begun to proliferate. Many places now have some equivalent of the EU Green Deal industrial plan or the USA’s Inflation Reduction Act and somewhat perversely, the initial emphasis has been fears regarding economies being “left behind” in a race to dominate the technologies of the future. On the one hand, hackles are rising over subsidies, unfair competition and protectionism. On the other, international organizations are becoming comfortable with a new language of climate justice and “just transition”. The world seems to be pulling in different directions and this is also true at a more quotidian level.

Changes to housing stock in the UK may seem a small concern when placed against the many changes required in the world, but emissions reduction is an odd kind of problem. Every small increment of reduction takes us further away from breaching a threshold which would lead to unwanted self-reinforcing outcomes. A great deal of modelling of climate and economy is currently defective and Earth system scientists are clear that problems are not restricted to climate. As I’ve noted elsewhere, in some respects it is weird that a self-imposed human artifice such as a finance system has become a reason not to do what we must do in order to save our and every other species from disaster. While this seems a rather grandiose way to frame the issue it does speak to some simple points:

- There is no credible path to net zero without massive and accelerated government financing.

- We need to start thinking differently about financing and its role in society…

- We have to stop thinking of retrofitting as an individualised and monetised cost-benefit market problem. It is collective or community focussed climate emergency planning.

- Properly conceived retrofitting is social redesign, but retrofitting will be pointless without more fundamental changes…

We need new thinking and initiatives. Yorkshire & Humber Engagement & Research Policy Network (Y-PERN) and similar elsewhere may yet start to offer that. At this stage, as Clive Spash among others suggests, there are only alternatives…

- This blog post is based on Competent retrofitting policy and inflation resilience: The cheapest energy is that which you don’t use, by J Morgan, C M Chu and T Haines-Doran, in Energy Economics, Volume 121, May 2023.

- The post represents the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Erik Mclean on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.