British households have low levels of financial resilience and are forecast a sluggish living standards recovery coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, Britain is the result of an economy defined by the low growth of the past 15 years and the high inequality of the past four decades, which pose risks for our economy, society, and democracy. The Resolution Foundation and LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance write that the UK is a stagnation nation, whose realities are regularly ignored and the trade-offs between different objectives wished away. They argue that Britain must be understood for what it is: a services superpower.

| #LSEUKEconomy |

|---|

With rising wages, higher employment, the provision of public services or support for those who fall on hard times, the British state and economy have delivered in the past. Between the Second World War and the turn of the millennium, real wages nearly quadrupled, while state spending on healthcare as a share of the economy almost trebled.

But that progress, and the strength it gives to our society and democracy, should not be taken for granted. There are periods when this underpinning of our social contract comes under pressure; when a clear route to a better tomorrow is lacking, the improvements people expect dry up and some groups are left wondering whether the country works for them. Britain in 2022 is in this undesirable position.

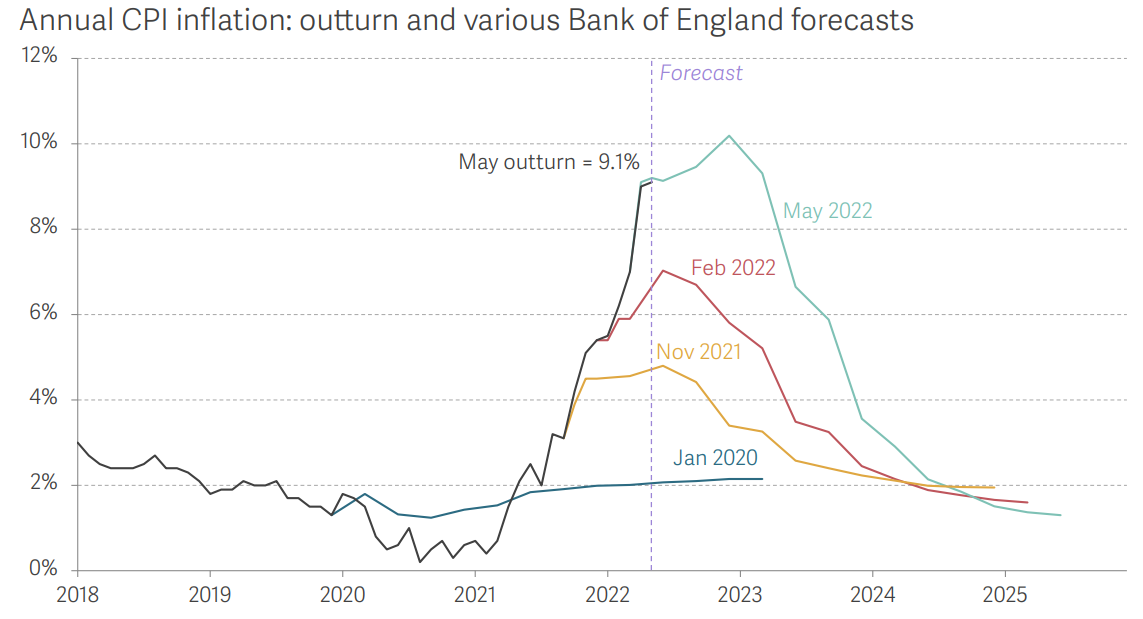

In 2022 the UK was meant to have started on the road to recovery following the ravages of COVID-19. Instead, our anxious focus on fast-rising case rates has, almost instantaneously, been replaced by one on surging prices: the first global pandemic in 100 years has been followed by the arrival of inflation not seen for four decades. Inflation has risen from close to zero at the start of 2021 to 9.1 per cent in May 2022, consistently surprising official forecasters (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Bank of England is forecasting the highest inflation in 40 years

Source: Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report, various; ONS, Consumer Price Inflation.

However, as pressing as today’s issues are, policymakers must lift their sights to broader challenges to ensure our shared prosperity. British households went into this crisis with low levels of financial resilience and are forecast a sluggish living standards recovery coming out of it: we’re set to take until the middle of this decade to return to pre-pandemic income levels. This is the result of an economy defined by the low growth of the past 15 years and high inequality of the past four decades, which pose risks not only for our economy, but to our society and democracy too. This makes the UK a stagnation nation.

On the eve of the financial crisis, GDP per capita in the UK was just 6 per cent lower than in Germany, but this gap had risen to 11 per cent by 2019. Our GDP performance would have been even weaker were it not for strong employment growth, with hours worked having increased by more than two and a half times the rate in France (11 per cent compared to 4 per cent).

This reflects a productivity slowdown far surpassing those seen in similar economies. Labour productivity grew by just 0.4 per cent a year in the UK in the 12 years following the financial crisis, half the rate of the 25 richest OECD countries (0.9 per cent). Having almost caught up with the economies of France and Germany from the 1990s to the mid-2000s, the UK’s productivity gap with them has almost tripled since 2008 from 6 per cent to 16 per cent – equivalent to an extra £3,700 in lost output per person.

Claims that these measures of economic progress mean little for ordinary workers are common but painfully wide of the mark. Weak productivity growth has fed directly into flatlining wages and sluggish income growth: real wages grew by an average of 33 per cent a decade from 1970 to 2007, but this fell to below zero in the 2010s. The result is that by 2018, typical household incomes were 16 per cent lower in the UK than in Germany and 9 per cent lower than in France, having been higher in 2007.

Low growth, productivity disparities, and high inequality

While Britons have been living with low wages for the last 15 years, inequality has been a problem for more than twice as long. The persistence of income inequality comes despite the success of the national minimum wage in reducing hourly wage inequality between the bottom and the middle. This reflects the top (largely men) continuing to pull away from the middle, lower earners working shorter hours and housing costs rising for poorer households even as interest rate falls boost living standards at the top.

Income and productivity gaps between places matter and both are high and persistent in the UK. Income per person in the richest local authority – Kensington and Chelsea (£52,500) – was 4.5 times that of the poorest – Nottingham (£11,700) – in 2019.

Meanwhile, 80 per cent of the income variation between areas we see today is explained by the differences back in 1997. And productivity disparities are larger still, with that between the leading city and potential high-performing others greater than in peer countries such as France. For example, London is 41 per cent more productive than Manchester whereas Paris is 26 per cent more productive than Lyon.

Low growth and high inequality are a toxic combination. When sustained they are a disaster for low-to-middle income Britain and the young in particular

The twin challenges that Britain faces – low growth and high inequality – are substantial issues on their own, but together they create a toxic combination.

Slow growth is always a problem, but even more so when lower-income households lack financial resilience: over one-in-four adults went into the pandemic saying they would not be able to manage on their savings for a month if their income stopped. Inequality seems to matter more when the economic music stops: the share of the public citing poverty and inequality as one of the most important issues facing the country rose from 7 per cent in 2010 to 19 per cent pre-pandemic.

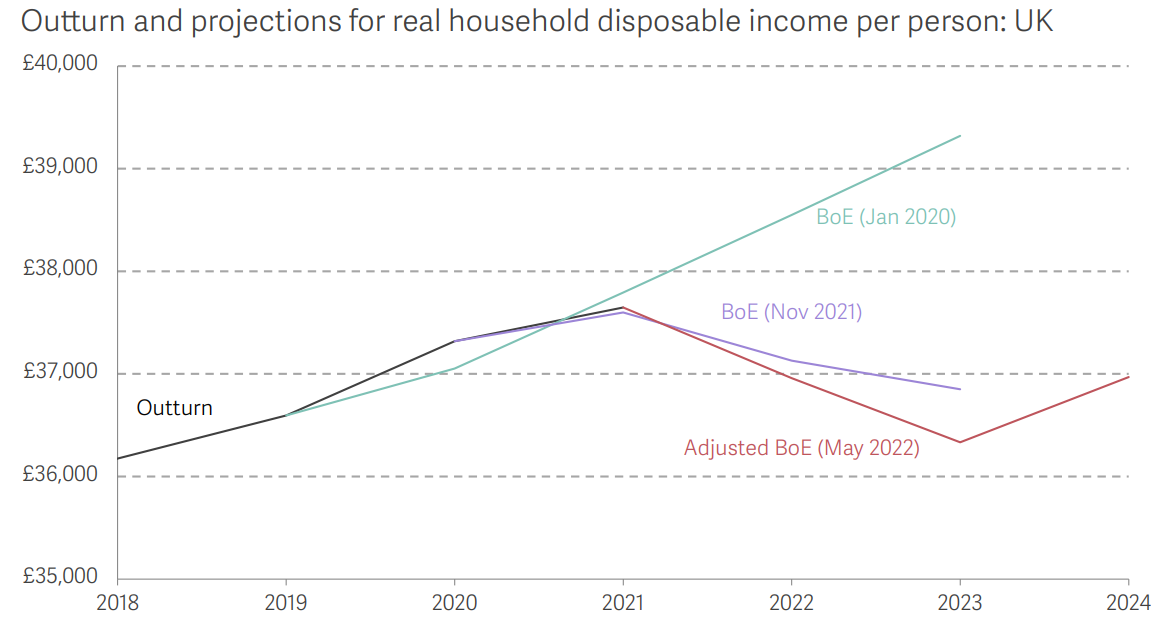

Figure 2. Household incomes could still fall by 1.8 per cent in 2022, even after additional cost of living support

Notes: Bank of England (BoE) forecasts. May 2022 forecast adjusted for the additional support for households announced by the Government in May 2022. Includes non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH). Source: ONS, National Accounts; Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report, May 2022; HM Treasury, Cost of living support factsheet: 26 May 2022.

The combined effects of Brexit, COVID-19, and the net-zero transition

Countries can go through phases of relative stability, but the UK in the 2020s will not be such a country. Long-standing demographic and technological shifts will continue and combine with Brexit, the aftermath of COVID-19 and the net-zero transition. These will bring significant disruption for some, but not the radical reset for our economy or large job losses many predict. Instead, rather than solving our stagnation, change risks reinforcing it.

BREXIT: The UK has suffered a broad-based fall in both openness and competitiveness. Between 2019 and 2021, UK trade openness fell by 8 percentage points (compared to a 2 percentage-point decline in France). The UK also lost market share across three of its largest non-EU goods import markets in 2021: the US, Canada, and Japan. Some sectors serving the EU market will shrink and others will grow as a result of less competition domestically. Fishing output will fall by 30 per cent, while food manufacturing could increase by more than 5 per cent. But these changes will not lead to a hoped-for manufacturing revival or more regionally balanced economy. UK manufacturing will change rather than grow, as high-productivity sectors like chemicals and electronics shrink even as lower-productivity food manufacturing expands. Wages in London, Wales and the Northeast will be hardest hit by the trade impact of leaving the EU on productivity which, across the country as a whole, means workers will be £470 worse off by the end of the decade.

COVID-19: COVID-19 caused huge changes to our economy and our lives. But many of the economic shifts wrought by the pandemic have unwound. The online share of retail spending shot up from 20 per cent to 38 per cent mid-pandemic but has fallen back to 27 per cent in the latest data – only 4 percentage points above the pre-crisis trend. Working from home has persisted for higher earners (the proportion of people who reported that they worked from home on a regular basis surged during the pandemic and remains high at 38 per cent of all workers in early 2022) but shows no signs of living up to claims that it would transform our economic geography or our productivity. There are 430,000 fewer people in work now than pre-pandemic and investment remains more than 9 per cent below its pre-pandemic level. It’s also, of course, been part of the inflation surge we are now all living through. If anyone ever thought that a global pandemic would bring big silver linings to our shores, they should think again.

NET-ZERO TRANSITION: The net-zero transition brings opportunities as well as change for workers and costs for consumers. But it is not a silver bullet for the UK economy. The net zero transition is crucial to not just the planet but in making the UK a greener and healthier place to live. However it comes with challenges in the here and now. There will be job change, rather than large-scale job losses. Major disruption will be felt by people as consumers, as our net zero commitments require significant investment in low-carbon infrastructure that has to be paid for. In the 2020s, this is principally about making our homes more energy efficient. The Government’s net zero strategy suggests we will be upgrading a million homes per year by 2030, but insulation installations have suffered a 90 per cent fall since 2013. If we remain on track, the challenge facing policy makers will be to ensure the costs are fairly borne: 72 per cent of low-income homeowners live in poorly insulated homes that will cost over £8,000 to bring up to standard. How these investments will be paid for should receive more attention than misplaced claims that net zero is a silver bullet that will hugely boost, or a catastrophe that will hold back, growth. There are new opportunities to be seized and green innovations to be exploited, but during the 2020s the main impact of the net-zero transition on GDP will be to change its composition, as we invest more but consume less, rather than its level.

These changes are the context within which the badly needed attempt to renew the country’s path to economic success needs to be placed.

Renew the UK’s economic strategy and end stagnation

Relying on supposed silver linings or silver bullets is part of a wider problem: the belief that a policy shift in one area holds the answer to stagnation. It won’t. Instead the task for the 2020s is to renew the UK’s economic strategy – its route to shared economic success.

Why is a strategy needed? First, because the challenges are large and have been sustained. 8 million younger Brits have never worked in an economy that has sustained rising average wages, while 25 million have never lived in a country where the top 10 per cent have had incomes less than five times that of the bottom 10 per cent.

Second, because those challenges and the change to come are interdependent. And third because the financial crisis and Brexit have blown up major components of the UK’s long-standing approach, which had itself been found wanting given the large and persistent gaps between people and places.

Important elements of a more comprehensive approach are visible, from the government’s focus on science, to the Labour Party’s green investment plans, or the Welsh government’s prioritisation of social partnership. But the test for a broader economic strategy is that it requires:

- goal orientation, being clear about the problem a strategy is trying to solve,

- clarity about context, understanding the type of country we are and the opportunities and constraints this brings, without nostalgia about the past or wishful thinking about the future,

- realism about trade-offs, recognising the tensions that always exist in setting strategy,

- policies of sufficient scale to plausibly move the dial,

- and, finally, staying power, because change takes time and short-termism has been a key weakness of the UK throughout the 20th century.

No one believes that Britain has such a strategy guiding policymaking and shaping private decision-taking today, and there is a recognition, from the chancellor downwards, that we cannot continue as we are. But a growing consensus about the problem is very different to being serious about the solution. Some argue we don’t need growth because it won’t translate into gains for ordinary households, ignoring the reality that a lack of growth is the cause of flatlining wages. More common is to recognise that growth is necessary, or that inequality is too high, but to be deeply unserious about what it might take to change things. The realities of modern Britain are regularly ignored and the trade-offs between different objectives wished away. We are short-term to our core.

Understanding our country: Britain is a services superpower

Not being serious begins at the most fundamental level: failing to understand what Britain’s 21st century economy actually looks like. Commentators often talk of the British economy as being narrowly built on banking, which is as misplaced as the claim that there is an easy route to turning ourselves into a German-style manufacturing superpower.

These pop narratives obscure the reality that Britain is a broad-based services economy, built on successful musicians and architects as well as bankers. We’re about ICT, culture, and marketing, as well as finance (whose fraction of total exports fell from 12 per cent to 9 per cent in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our services specialism does not lie behind our recent underperformance: on average, services-led economies tend to be richer than manufacturing-driven ones. It is also perfectly consistent with rapid export growth: global demand actually grew faster in our key export industries than in China’s in the decade to 2019, but China’s exports grew twice as fast.

We have manufacturing strengths too: pharmaceuticals, aerospace and beverages stand out. But the services-led nature of our economy is not going away. The things countries are good at are highly persistent: of the top 10 products the UK was most specialised in back in 1989, seven were in our top 10 in 2019. Even Brexit, the biggest shake-up to our economic place in the world in decades, will have little impact on the balance between services and manufacturing. Recognising the nature of our economy is not the same thing as welcoming all aspects of it, but an economic strategy that fails to understand it is no strategy at all. It will leave us without a clear view of how growth is achieved, exposed to policy mistakes, and failing to address the challenges being a services-led economy brings: upward pressure on inequality between people and places. Jobs in tradable services are 80 per cent more likely than average to pay in the top 5 per cent while services exports are concentrated in the highest-wage areas. Wrestling with this is essential, and possible. France is services focused like us but has much lower inequality.

Fundamentally we need to recognise that the path to future prosperity lies in being a better version of Britain, not a British version of Germany.

Explore our dedicated hub showcasing LSE research and commentary on the state of the UK economy and its future.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post summarises Stagnation nation: Navigating a route to a fairer and more prosperous Britain,

- a report of The Economy 2030 Inquiry, the Resolution Foundation and LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). It is funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Paul Fiedler on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Came across this looking for serious pieces about Britain’s economic future. Worryingly, there is rather less of these than might be expected. I would agree with the main argument but see little sign of its central message translating into consistent policy making. A major part of the problems we face are a result of over centralization and inconsistency of policy making. There is recognition of the former but the policy outcomes are pathetic. There is no real devolution of power and crucially resources. The second issue is the result of our first past the post system. It results in governments two thirds of the time many of whose members do not believe in government. So sensible measures like Regional Development Agencies and measures to fast track large infrastructure projects get binned or neutered. The almost complete lack of interest in the training and education of the majority who do not go to university is reflected in persistent underfunding.

I hold the belief that centuries of relative abundance in the Western world have brought us to a point of decline, where politicians often prioritize saying and doing what resonates with the immediate public sentiment, only for these promises to be quickly forgotten, akin to the memory span of a goldfish. Many commitments are made with little intention of follow-through, and there seems to be a lack of accountability for actual accomplishments. While this perspective may sound like the lamentations of an old-timer but I think it reflects the current state of affairs.