Scholars and practitioners agree on the relevant role of corporate culture on economic performance, but there has been no clear evidence of its effect on firms’ creativity. In a lab experiment, Gary Charness and Daniela Grieco find that group-oriented environments promote creative task performance more than environments where individualism prevails. They write that employers who need to rely on creative ideas and solutions must turn their attention to their corporate culture.

Organisational creativity is the successful implementation of creative ideas, such as new products, processes or services, or even new policies, within the organisation. Although shaped by individual members, this type of creativity depends greatly on the organisation’s features. A pivotal role is played by “corporate culture”, which can be described as an informal institution comprised of a strong set of managerial values that define the way to conduct business. The firm’s corporate culture with respect to creativity and innovation is represented by the sum of immaterial resources, institutionalised mechanisms and tacit tools it uses to encourage (or discourage) novel behaviours. Corporate culture acts as a guide or constraint in situations where employees face choices that cannot be properly regulated by formal contracts (for example, when there are unforeseen events). It doesn’t come as a surprise that business executives strongly believe that an effective corporate culture may increase the creativity content of their decisions.

While scholars and practitioners agree on the relevant role of corporate culture on economic performance, there is no clear evidence of its effect on firms’ creativity. There are still many unanswered questions related to the appropriate measure for corporate culture, the channels through which it affects performance, the relationship between stated corporate values and actual outcomes within companies, and the type of corporate culture most conducive to higher creativity. Our study attempts to make some progress on answering these questions. To this purpose, we test experimentally the effect of corporate culture on creativity, which, to the best of our knowledge, no previous research has done. A crucial – but certainly not the only – dimension of corporate culture involves whether people are encouraged to work independently (“individualistic”) or in groups (“group-oriented”). These variations may very well be differently conducive to creative performance.

First contribution

The first contribution of our work was in establishing a culture in the experimental laboratory. While we agree that it does not seem feasible to develop a full-blown culture in the lab, we do establish at least a minimal framework and offer some useful results. In our design, firms are stylised as groups of three people where each person completes an individual differentiated task that is either verbal, mathematical, or graphical. Each session included five groups. Creative output was produced at the individual level (although within-group discussion was allowed), with each group completing all three tasks.

For the three individuals in each group to develop a sense of group identity, we made them compete in their individual tasks with members of other groups. Various important works have stressed the importance of group identity, which is ‘the ideal motivator if the effort of a worker is either hard to observe or hard to reward’ (p.10). One of the seminal works on social identity theory suggests that generating competition between (or among) groups is very effective in fostering the identity-formation process. Competition with out-groups engenders in-group enhancement, stimulates in-group effort, and induces group-contingent social preferences.

Second contribution

As a second contribution, we consider the interplay between formal and informal corporate institutions by testing whether an incentive structure (a formal institution), combined with corporate culture (an informal institution), can be used to foster creative outcomes.

From interviews with business executives it emerges that the effectiveness of corporate culture depends not only on the alignment of values and norms, but also on possible interactions with formal institutions, such as compensation incentives. A firm can shape the process of preference formation by setting incentives aimed at fostering the desired type of corporate culture. For instance, incentives may induce workers to be more helpful to each other or stimulate competition among them. The reward system is a primary way to achieve control over the behaviour and attitude of an organisation’s members. It specifies the contribution the organisation expects from members and the response individuals expect to receive according to their performance. A culture can be established by aligning the financial interests of executives to it or by setting employees’ compensation practices in that direction. Compensation systems are also believed to affect culture and performance through the self-selection of organisational members. The incentive system – who gets rewarded, why, and how – is thus “an unequivocal statement of the corporation’s values and beliefs” (p. 130).

Although there is mounting evidence that the performance of organisations depends on both economic incentives and culture, very few papers look at the interplay between these two factors. As a result, we have a rather limited understanding of how incentives and corporate culture interact in general and, particularly, when considering creative endeavours. Our experiments aim to help bridge this gap.

Third contribution

As a third contribution, we provide a measure of the effect of corporate institutions on values. We do it by administering a questionnaire on corporate values after the subjects have participated in the experiment. This helps to establish how incentives can foster a group culture by affecting values. To be able to speak of culture, the value system that the incentives scheme intends to reflect should be embraced by the individuals and shared by the organisation’s members. We thus assess whether receiving incentives, as individuals or as a group, establishes a corporate culture that can be classified as “individualistic” or “group-oriented”. Finally, we explore whether and how creative performance, as compared to performance in a standardised, non-creative task, is affected by corporate culture.

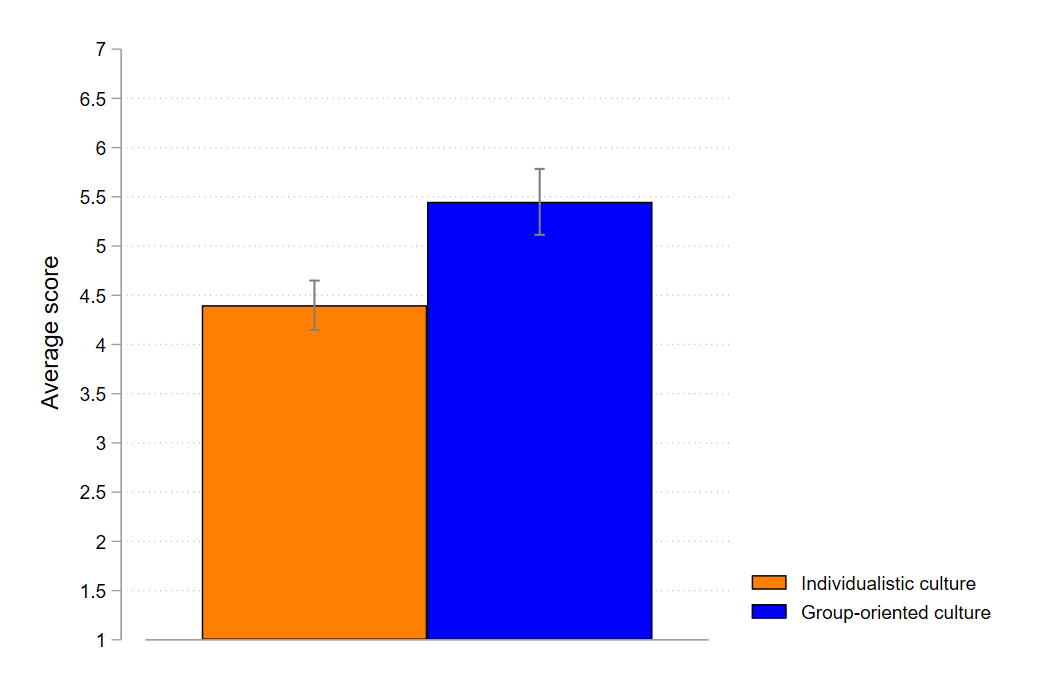

Our results are clear and yet perhaps surprising in some respects: when a group competes against an out-group and incentives are set at the group level, this serves as a social cue that prompts the formation of a sense of group identity and induces a stronger pro-social attitude among the group members. When this is shared, a social norm of high effort emerges, with better creative performance. The proportion of groups who share a pro-social attitude is much higher when incentives are set at the group level, corresponding to a much higher creative score for the group. Figure 1 compares the average score in case of individualistic versus group-oriented culture.

Figure 1. Performance in the creative task and corporate culture

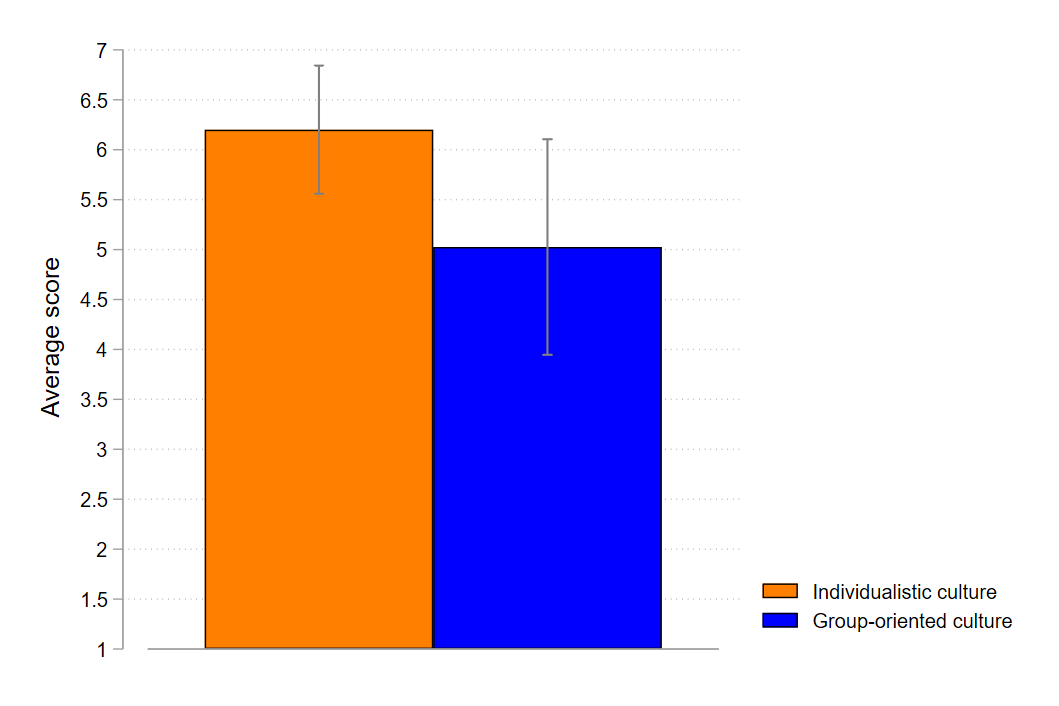

Our experimental evidence thus indicates that group-oriented environments promote creative task performance significantly more than environments featuring a high degree of individualism. The lab-created corporate culture affected performance in creative tasks but had no effect on performance in standardised, non-creative endeavours. When the task is creative, the presence of a norm for desirable action appears to multiply the benefits of financial incentives. Figure 2 considers a standardised task and compares, as in Figure 1, the average performance in case of individualistic versus group-oriented culture.

Figure 2. Performance in the standardised task and corporate culture

The reason why the type of task interacts with the formation of a social norm of high effort can be related to the specificities of the creative tasks, which tend to be more complex, intrinsically rewarding, and associated with more uncertainty about the value of output.

In practical terms for companies: creative employees are those who have a stronger commitment towards the organisation, and the level of commitment is highly correlated with the strength (and type) of corporate culture. Employers who need to rely on creative ideas and solutions cannot afford to disregard the type of culture that prevails within their firms.

Figure 3. Group-oriented culture favours experimentation and novelty

- This blog post is based on Creativity and Corporate Culture, The Economic Journal (2023)

- The post represents the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.