Informality prevails in Africa, especially among women. Eighty-eight per cent of working African women were employed in the informal economy in 2022. Even among countries that stand out in implementing gender equality reforms, significant gaps between formal law and practical experiences emerge. Simeon Djankov and Karolin Lehmann write that addressing these challenges is crucial for African businesses seeking international presence.

The absence of gender legal rights has profound consequences, particularly when it comes to harnessing the potential of female workers in the formal labour market. Recent analysis from the International Labour Organisation (ILO) underscores the prevalence of informality in economies grappling with gender disparities. In 2022, 88 per cent of working women in Africa were employed in the informal economy, a staggering share. In numerous African economies, the stark reality is that female talent remains untapped by domestic and global businesses due to legal barriers. This gap not only stifles the potential of working women but also hampers business investment in Africa and the international standing of African companies.

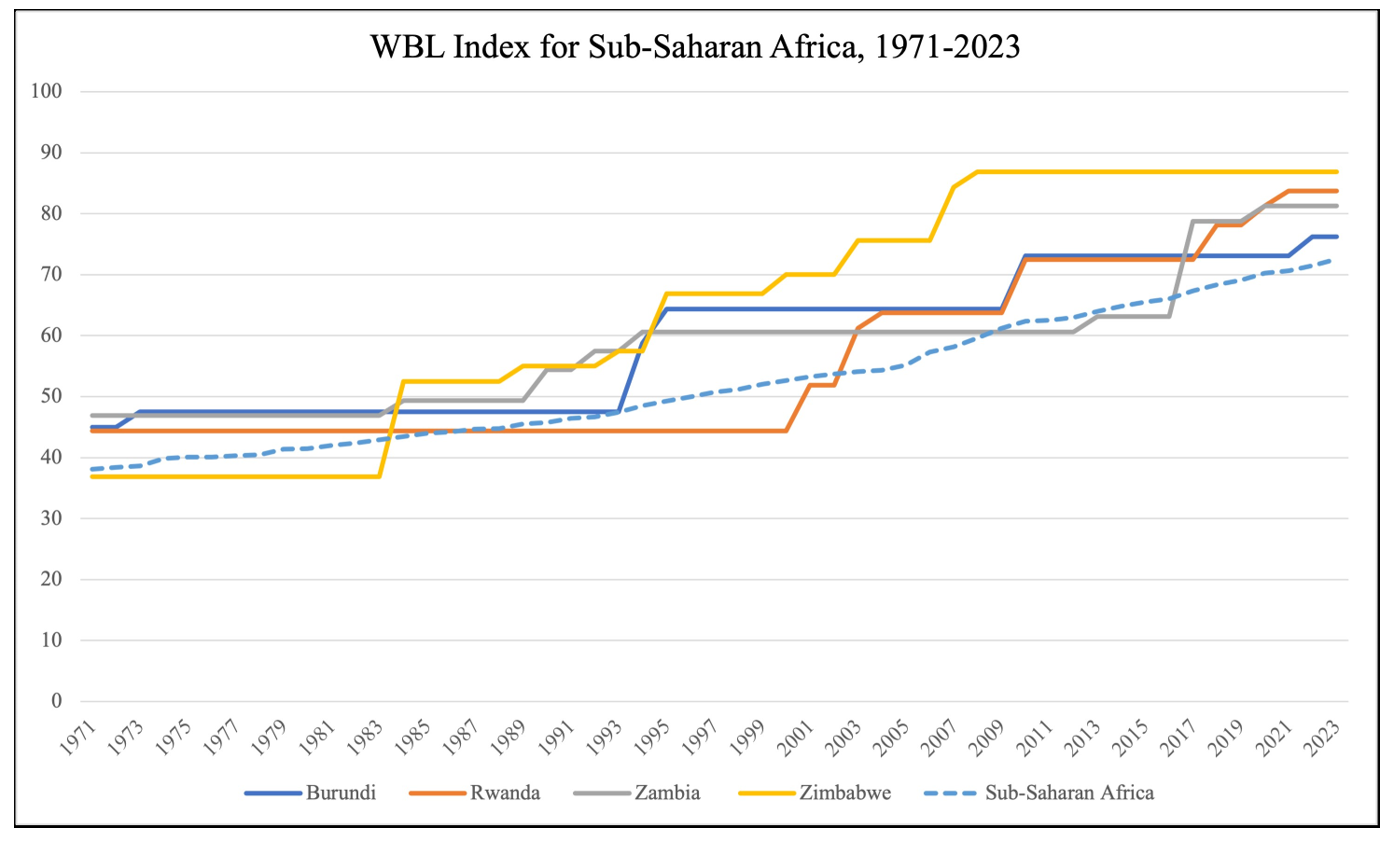

Since the Beijing Conference on Women in 1995, legal systems have undergone various gender reforms across the world. This is especially true in Africa, where post-colonial transformations featured gender equality as a prominent goal. The World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law Index serves as a useful tool for tracking the evolution of legal rights for women in the past half century. The Africa regional average of the index in 2023 is just below the global trend line with a score of 73 out of 100. The main reforming countries when it comes to formal legal rights are Rwanda, Burundi, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. While these four countries are performing well on paper in supporting women’s rights, significant gaps between formal law and practical experiences emerge.

This is especially true when looking at the labour market dynamics, where the improvements in legal frameworks do not easily translate into improved outcomes for women. Despite improving scores on gender equality, these countries all navigate dual legal systems where customary practices prevail and where women find themselves unable to benefit from newfound legal protections. This discrepancy becomes apparent when examining the prevalence of women in the informal economy, where they are more likely to be employed in precarious roles, such as agriculture or at the lowest tiers of global supply chains.

Women often encounter obstacles in accessing formal employment due to antiquated societal norms, prompting many to turn to the informal sector for economic opportunities. The absence of comprehensive gender reforms within the formal employment sector further exacerbates gender inequalities, with issues like unequal pay and lack of support for motherhood persisting. The issue of customary law prevailing over statutory law in much of Africa further complicates matters, reinforcing traditional gender roles and impeding the implementation of gender-sensitive policies.

Some country examples manifest these challenges (Figure 1). Rwanda is often highlighted as a model for effective legal changes promoting gender equality. With a WBL score of 84, this achievement stands out even more when compared to neighbouring countries like South Sudan and Congo, where women’s legal rights are still nascent. The compelling story emerges from the notable influence of robust female leadership in rebuilding the nation after the genocide, creating a narrative that underscores the advocacy of women in politics and business for enhanced economic empowerment for all Rwandan women. Yet, in terms of formal employment, women still fall behind by roughly 5 percentage points, impeding their economic rights.

Figure 1. Progress in gender legal rights in Africa

Note: Hyland, Djankov, and Goldberg (2020) introduce the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law (WBL) index as a measure of legal equality between men and women. The WBL index charts the inequality in legislation that a woman faces as she navigates her working life, from the time she can enter the labour force through retirement. Scores range from 0 to 100, where a score of 100 implies that there are no legal inequalities between men and women in the areas covered by the index. The most recent data show that the global average WBL score in 2023 is 78, implying that, on average, women around the world have about three-quarters the rights of men when it comes to laws affecting their economic opportunity. Source: Authors’ own calculations.

Over the last five decades, Zambia has undergone two significant waves of legal change aimed at enhancing women’s rights. These changes appear to be closely tied to the endorsement of international treaties, indicating that external influences have played a significant role in driving gender-related legal reforms in the country. In Zambia, legal adjustments frequently diverge from established practices. The presence of a dual legal system has impeded tangible improvements in women’s legal and economic rights, with customary law exempted from the anti-discrimination provisions in statutory law. As long as there is a disparity between customary and statutory law, gender inequality persists. This dynamic is further amplified by the gender gap of informal employment, which stands at 90% for women in Zambia. Despite advocacy from various women’s organizations urging the alignment of customary law with statutory provisions on women’s economic empowerment, this transformation has yet to occur.

A third example illustrates how to handle long-held views that African values do not match favorably with equal legal rights for women. Zimbabwe’s trajectory towards women’s rights looked promising, with legal changes coinciding with the UN’s Decade of Women in the 1980s. However, subsequent government actions, such as Operation Clean-up in the late 1980s, created setbacks. The government’s diminished support for women’s rights reflected political concerns about the alleged incompatibility of gender equality with African values. This rhetoric permeates parliamentary debates and has resulted in laws that had given women broader rights being repealed.

Finally, in the six decades since achieving independence Burundi has implemented some legal changes aimed at ensuring equal social and economic treatment for both genders. However, with an informal employment rate of 99 per cent for women, issues concerning land ownership, inheritance rights and secure employment options remain. Despite successive governments amending legal texts, they acknowledge challenges in their application. Moreover, positive strides in legal changes have sometimes been counteracted by subsequent regressions. The inconsistency in the legislative process reflects a reluctance to prioritize the social and economic rights of women over traditional views that women should stay at home.

These case studies also underscore the pivotal role women have played in the struggle for independence and nation-building in Africa, even when the benefits of these struggles in terms of better legal protections have not been realized. Despite women’s involvement in the reconstruction of their countries, the translation of legal rights into tangible change has been limited. The prevalence of informal employment has significant implications for businesses investing in these environments.

The reliance on informal employment results in a less stable and skilled workforce, depressing productivity and overall economic development. Gender disparities within the formal sector also hinder innovation, limiting the potential for a dynamic business environment. Moreover, businesses may face challenges in adhering to ethical and socially responsible practices when operating in contexts where customary law prevails over statutory law, potentially affecting their global branding. Recognising and addressing these challenges is crucial for African businesses seeking international presence, emphasizing the need for corporate engagement in advocating for gender reforms and supporting initiatives that promote inclusive economic development on the continent.

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock.

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.