UK business improvement districts (BIDs) are partnerships with powers to decide on a compulsory surtax to pay for additional services, such as increased security, business support and recreational events. Research has shown that they reduce local crime. Francisco Nobre and Stefano Cellini write that they also lead to increases in house prices and may lead to gentrification.

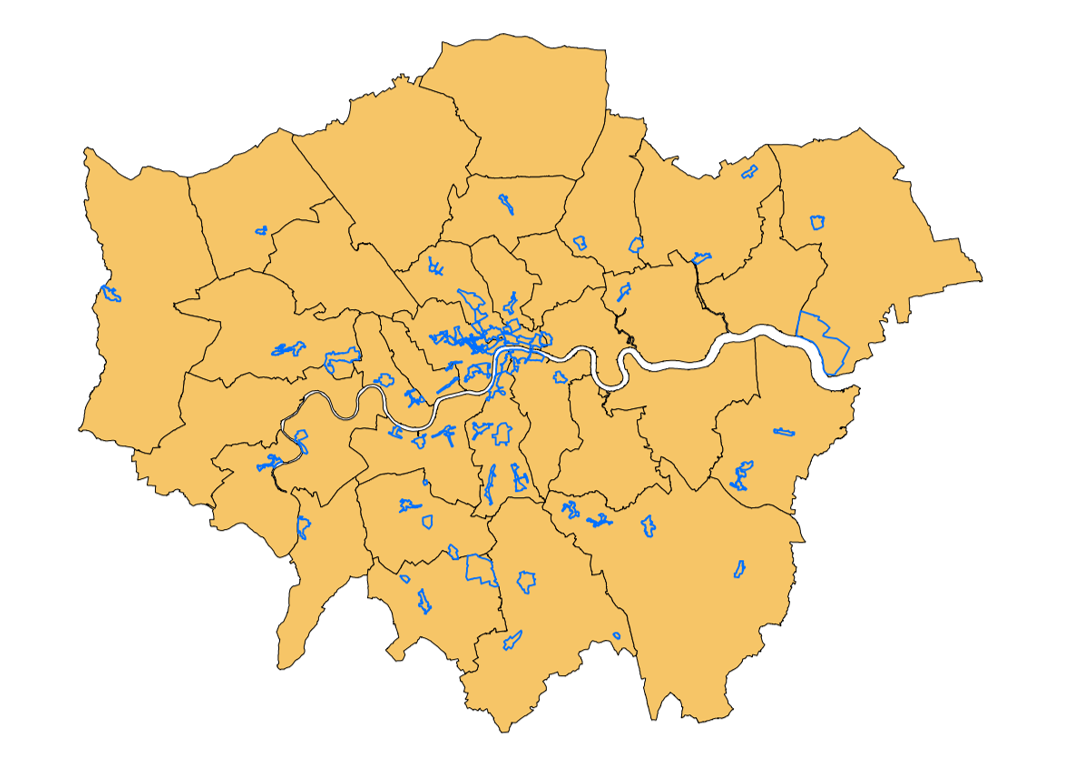

Would you live in a neighbourhood where local shops and businesses pay to keep it safe and clean? The question is topical for cities in the US and in the UK, where local businesses have been establishing so-called business improvement districts (BIDs) to collect funds to spend on the quality of their community. Since 2005 more than 65 BIDs have been created in the sole metropolitan area of London, a fifth of the whole population of such districts in the UK (see figure 1). We take the British capital as the setting to explore whether BIDs increased house prices and impacted their neighbourhoods. Overall, house prices rose by at least three per cent within their boundaries and plausibly influenced the local resident household mix.

Figure 1. Map of London BIDs

Formation and goals

BIDs in the UK consist of a partnership of occupiers (or owners) of commercial property within their local authority, with powers to decide on a compulsory surtax, ring-fenced to pay for additional services and improvements in their locality. These services are supplementary to the local authorities’ expenditure in the area and range from increased security measures to business support and recreational events.

Groups first propose the formation of a BID to local businesses to gather their opinions, then organise a vote on whether to go ahead with the project. Approval requires a simple majority of both the total number and the rateable value of votes cast, meaning that the businesses that approve it must represent at least 50 per cent of the total value of commercial properties within the BID. Assuming this vote is positive, a management structure comprising representatives of relevant stakeholder constituencies is created, and a strategy developed. The BID operates for a five-year term, and its renewal is subject to another ballot.

In London, BIDs have a median annual budget (in 2010 prices) of £338,474, with Central London BIDs spending in the order of millions per year. Around 86 per cent of them charge a levy between 0.5-1.5 per cent of the rateable value of the commercial properties, with those charging higher rates having smaller budgets.

Prior research

Prior research has shown that BIDs are quite effective in reducing local crime. They spend an average of 36 per cent of their budget on neighbourhood crime and environmental quality. In Los Angeles, the reduction ranged between six and 10 per cent from 1990 to 2002, with a more noticeable decline in serious crime. In England and Wales, decreases around two per cent per quarter took place between 2012 and 2017, with stronger effects for shoplifting, anti-social behaviour and public order-related offences. Researchers noticed a displacement of criminal activity to commercial areas one to two kilometres away from the BID.

In New York City, BIDs had a lasting effect on commercial property values, which rose by almost 16 per cent, while for residential ones the impact was felt during the BID creating process but prices decreased again once they were formed. While these studies find that BIDs make a difference for local crime and commercial properties’ value, we investigate the effects on residential housing markets.

Our results

We present evidence of localised house price capitalisation of these “extra” public services that are privately provided, by constructing a two-decade long, geocoded dataset comprising both property transactions and housing planning applications for the Greater London Area.

We estimate that BID formation led to an increase of at least three per cent in house prices and these benefits spilled over to the surrounding areas up to 200 to 300 meters from district boundaries. These effects were driven by an increase in demand for BID-provided goods and services. We failed to find differential underlying trends in housing supply before and after BID openings.

Making use of available budget figures and BID levy rates, we calculate that for each £1 spent by a district, the public gained around £1.26, which is a measure of the societal value of these private expenditures. Since residents do not contribute directly towards BID funds, the increase in house prices may also be seen as a positive externality for incumbent households.

We also provide longer-run associations between neighbourhood exposure to BID and resident household profiles. Comparing the census-reported sociodemographic characteristics from 2001 to 2021 between blocks within BIDs and blocks outside BIDs, we show that BID neighbourhoods experienced a different trajectory in household characteristics. The most salient differences arise in ethnic composition and professional occupations. Blocks within BIDs present a higher persistence of white households and lower growth in minorities – even though white populations decreased and minority ones increased throughout London.

The share of managerial and administrative professionals among BID residents grew more. This adds to the consistent evidence on the amenity-driven demand for certain neighbourhoods and its effects on neighbourhood composition. Research by urban economists finds that rising amenity values in urban areas, like security and liveliness (leisure and recreational facilities), drive downtown appeal, particularly for higher-educated professionals.

Conclusion

Our findings raise important points regarding the role of BIDs for their neighbourhoods. Local BIDs may not only have effects on their investment targets but also result in broader economic consequences. Neighbourhoods within BIDs enjoy subsequent services and amenities, but also undergo gentrification, in line with other empirical findings on urban revitalisation.

- This blog post is based on The Value of Business Improvement Districts: Evidence from Neighborhoods in London.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock.

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.