Governments around the world are wondering how to expediently put money in the hands of the millions of firms struggling in the health crisis. Look no further: just pay your bills on time. If governments paid all receipts due to their contractors within 45 days, some $4.65 trillion in fresh liquidity would enter the private sector. To put this amount into perspective, it is of the same order of magnitude that G20 countries have so far committed ($6.3 trillion) for fiscal support measures to alleviate the effects of the pandemic.

Speed is not characteristic of the public sector, especially when it comes to paying bills. Data from the World Bank’s Contracting with the Government indicator show that procuring entities take on average 14 weeks (about 100 days) to process the final payment for public works contracts. We calculate the size of the accounts payables for countries that delay their payments on completed public procurement projects beyond 45 days. The figure is a staggering $4.65 trillion, suggesting that governments are missing an obvious liquidity channel at their disposal. True, much of this delay is with different ministries and agencies, as well as with municipal governments. Someone – be it the prime minister or the head of the crisis response taskforce – needs to give the go-ahead so money is dispatched on time.

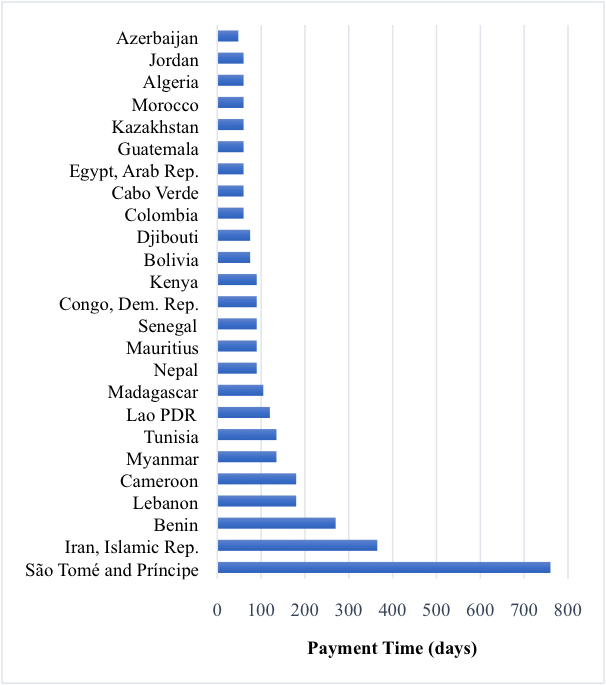

Delays vary broadly across countries, from 48 days in Azerbaijan to 760 days in São Tomé and Príncipe (Figure 1). For example, in Angola, it takes on average 180 days for a business to receive final payment from the government. In Guinea, it takes on average 365 days. Only about 28% of countries pay contractors within 45 days from the completion of works. Many companies, their contractors, and employees are struggling without work during the lockdown while waiting for the government to release payments for the work they have already done.

Figure 1. Delays in processing final payments

Source: World Bank’s Doing Business database

Yet fresh money is of the essence to support companies facing government-mandated lockdowns and collapsed demand. Recent analysis shows that the survival time of small firms in Southern Europe and emerging markets during the pandemic ranges between 8 weeks (for retailers) and 19 weeks (for chemicals and plastics manufacturing companies). Without an inflow of fresh money to cover their fixed costs, most companies will have to shut down within 2 to 5 months from the start of the COVID crisis.

Paying the private sector on time for work already done is not just about having cash on hand. It also prevents companies from taking up further debt in order to survive. The evidence is clear: the faster the government pays its dues, the fewer firms needing a loan. Our earlier blog discusses several other options for firm financing that do not involve piling debt burdens.

Governments should start paying outstanding invoices on time to provide companies with the money they need to survive the health crisis and the recovery period that will follow. This step is needed now, with the private sector facing an unprecedented crisis. Moreover, timely payment of bills to businesses should be standard practice that all procuring entities follow, through the recovery phase and beyond. Paying companies within a reasonable amount of time for work they have delivered should not be an emergency measure. It should be the norm.

Erica Bosio and Simeon Djankov will take part in the LSE online event “Government Assistance to Struggling Businesses in the COVID-19 Crisis”, Tuesday 19 May 2020, 3:00pm to 4:30pm. For more information and to sign up, click here.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Pepi Stojanovski on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Erica Bosio is a researcher at the World Bank Group, where her work focuses on public procurement. Previously, she worked in the arbitration and litigation department of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton in Milan. She holds a Master of Laws from Georgetown University and a degree in law from the University of Turin (Italy).

Erica Bosio is a researcher at the World Bank Group, where her work focuses on public procurement. Previously, she worked in the arbitration and litigation department of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton in Milan. She holds a Master of Laws from Georgetown University and a degree in law from the University of Turin (Italy).

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at LSE and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank. He is the founder of the World Bank’s Doing Business project. He is author of Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account (2014) and principal author of the World Development Report 2002. He is also co-editor of The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism (2014).

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at LSE and a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank. He is the founder of the World Bank’s Doing Business project. He is author of Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account (2014) and principal author of the World Development Report 2002. He is also co-editor of The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism (2014).

Emilia Galiano is an economist at the World Bank, where she focuses on private sector development in the context of public procurement. Previously she worked in the microfinance sector and then started her career at the World Bank as a knowledge professional. She holds an M.A. in international development from Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and an M.A. in international relations and diplomacy from Bologna University (Italy).

Emilia Galiano is an economist at the World Bank, where she focuses on private sector development in the context of public procurement. Previously she worked in the microfinance sector and then started her career at the World Bank as a knowledge professional. She holds an M.A. in international development from Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and an M.A. in international relations and diplomacy from Bologna University (Italy).

Nathalie Reyes is an analyst in the growth analytics unit at the World Bank. Her work focuses on public procurement, business regulations, and private sector development. Prior to joining the World Bank, Nathalie worked in the Inter-American Development Bank and Universidad Javeriana in Bogota, Colombia. She holds a Master’s degree in development economics and public policy from Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and a degree in economics from the Universidad Militar Nueva Granada.

Nathalie Reyes is an analyst in the growth analytics unit at the World Bank. Her work focuses on public procurement, business regulations, and private sector development. Prior to joining the World Bank, Nathalie worked in the Inter-American Development Bank and Universidad Javeriana in Bogota, Colombia. She holds a Master’s degree in development economics and public policy from Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and a degree in economics from the Universidad Militar Nueva Granada.