This was published by the China Global South Project on 15 October 2021. China Foresight is affiliated with the China Global South Project and regularly provides opinion pieces for the weekly IDEAS China Global South newsletter. Click here to subscribe to the newsletter.

With environment and climate change concerns at the centre of attention ahead of the upcoming COP26 in Glasgow, Beijing is increasingly seeking to portray China as a leader in combatting climate change and environmental degradation.

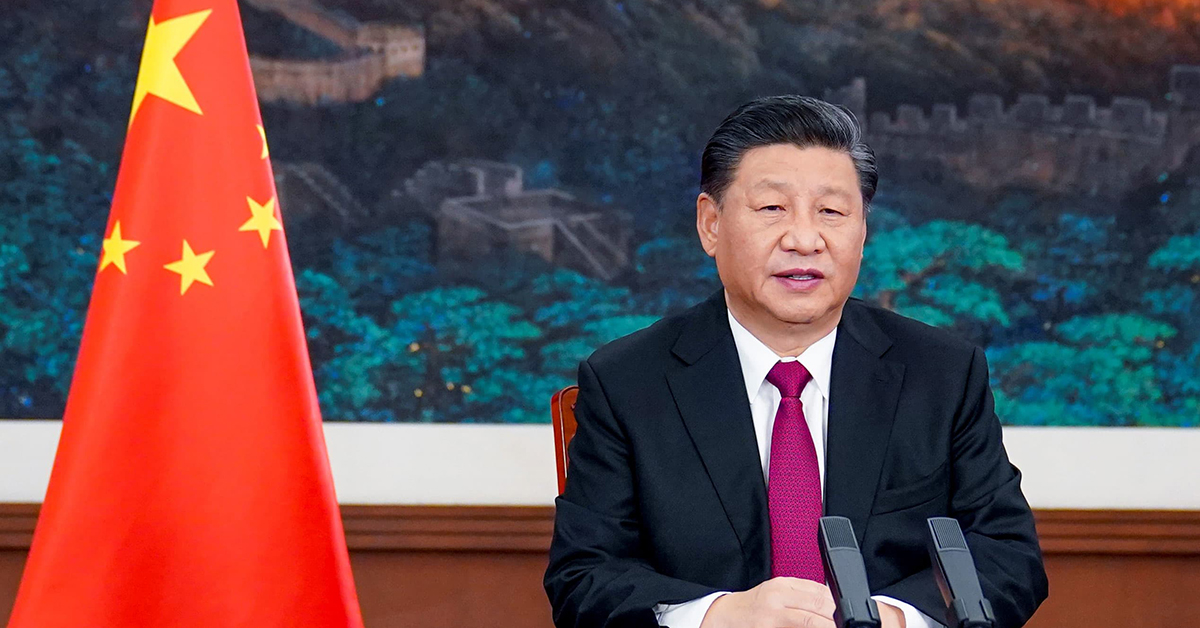

This week, at the COP15 Biodiversity Conference, Xi Jinping announced the creation of a $233 million biodiversity fund, with the objective of protecting biodiversity in developing countries. This signifies progress in the direction of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework, drafted earlier this year. It’s also another sign that China is increasingly mindful of its environmental relationship with the developing world, following the announcement that it would halt all overseas coal financing last month. Both policies are significant in part because they were announced by Xi Jinping himself, reflecting the importance that top leaders assign to the topic.

Xi’s comments at COP15 give a taste of what’s to come at COP26. He emphasized the need for a fairer global environmental governance system, which practices ‘true multilateralism’ that is both balanced and equitable. Climate change and biodiversity loss are evidently felt most urgently across the Global South, where vulnerability to disappearing ecosystems, natural disasters, and irrigation issues affect the livelihood of millions. Yet it is also the Global South that will drive a massive increase in energy demand over the coming decades. The themes of justice and equity (and differentiated responsibilities) are likely to pervade China’s positioning at COP26.

At the centre of all of this is of course Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, whose infrastructure roll-out has already affected biodiversity across the Global South. While it is difficult to precisely detail all the impact on biodiversity a global initiative such as the BRI will have, the initiative has centred on regions such as Southeast Asia and Central Asia that are most urgently affected by the accelerating extinction of numerous species.

In Indonesia, for instance, a Chinese-funded hydropower project on the Batang Toru River has drawn extensive criticism for endangering local wildlife. The deforestation necessary to put the project on the map pushed the already endangered Tapanuli orangutan population to the brink of collapse. Over the last three generations, the population of Tapanuli orangutans dropped by 83%.

Questions remain as to how effective the Kunming declaration and fund can be at delivering the structural change needed to transform China’s transnational supply chains, infrastructure expansion, and embedded financial interests which contribute to the destruction of Earth’s natural habitats. Even when sized up against the Chinese government’s unique capacity to implement far-reaching changes across various sectors, demonstrated by regulatory changes over the past few months, entrenched domestic interest groups and structural imbalances in China’s economy will certainly represent a hurdle to swift action on economic policies that further environmental priorities.

Li Lun, the Director of Global Policy and Advocacy at WWF International, said ‘the Kunming Declaration is a show of political will and adds much-needed momentum by clearly signalling the direction of travel to address biodiversity loss [but] its impacts will lie in how it is put into action. It is still critical for governments to turn these words into reality.

Climate change mitigation is of course not solely China’s responsibility. Indeed, as we have written previously, China is often called out to offset responsibility on part of the European and US private sector, especially on topics such as coal finance. But as the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, Beijing certainly has a key role to play. And China’s recent energy crisis indicates that a rapid transition to clean energy and net-zero will not be plain sailing.

After two decades of going out to access markets across the Global South, Chinese leaders and policymakers are confronted with the growing environmental consequences that infrastructure building and resource extraction bring about.

With global reach comes responsibility for the global commons. China has shown it can go out – it is high time for Beijing to demonstrate that China can also go green.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

The blog image, “Greenhouse Gases from Factory, Factory in China“, is licensed under CC BY 2.0.