Lukas Fiala

China’s recent diplomatic activism in the Southwest Pacific – signing a bilateral security agreement with the Solomon Islands followed by an ambitious 10-day tour across the region by Foreign Minister Wang Yi – has raised more than a few eyebrows across Western capitals. Unsurprisingly, many have been weighing in on what the drivers behind China’s engagement may be, discussing Beijing’s desire to project power within the second island chain, China’s emergence as a more interventionist power propping up friendly governments, or the willingness to protect Chinese assets and citizens in the region.

While we should certainly acknowledge all these as potential drivers of China’s engagement, another important but neglected reason is the evolving nature of Chinese statecraft towards using ‘security’ as a tool to consolidate diplomatic relationships and build alternative diplomatic arrangements to US-led institutions. Indeed, if the leaked draft of the China-Solomon Islands agreement on security cooperation – which was not authenticated – is anything to go by, then China has embraced this opportunity to present itself as an active security provider by enabling Honiara to request Chinese police or military forces to assist in maintaining domestic stability and security.

From Africa to the Southern Pacific, security has thus become a key tool to consolidate China’s diplomatic footprint

While significant in and of itself, the bilateral agreement should be interpreted within China’s broader plan for the Southwest Pacific. The key objective of Wang Yi’s tour was to convince regional states to sign up to a sweeping development agenda spanning economic, public health, cultural and security cooperation. Though the whole deal was rejected at the second China-Pacific Islands Foreign Minister’s meeting in Fiji last week, it demonstrates China’s willingness to become a key security actor in the Southwest Pacific across different domains. The proposed deal reportedly proposes China to train regional police forces as well as hold a first China-Pacific Islands Countries ministerial dialogue on law enforcement capacity and police cooperation – the first of its kind. Cybersecurity and rules for data governance are also mentioned, thus going well beyond an interpretation of Chinese interests as solely concerned with establishing a basing facility.

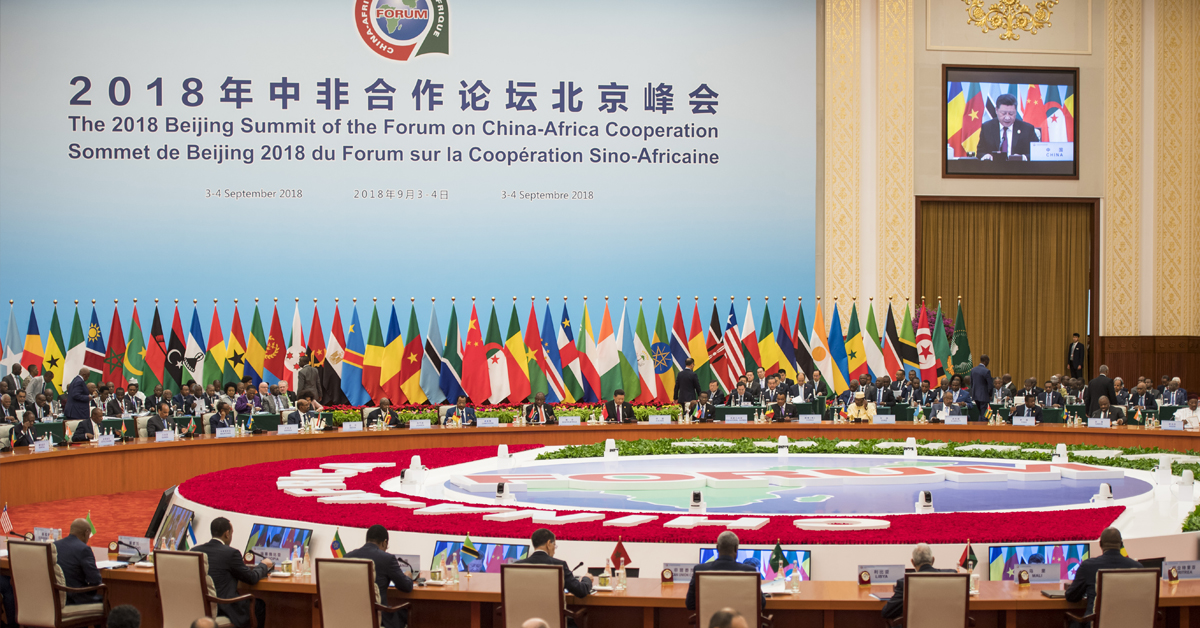

These broad ambitions reflect how China has become increasingly willing to formalise security arrangements with foreign counterparts to consolidate existing diplomatic relationships while also building alternative arrangements for diplomatic exchange. Chinese diplomats may have thought of their previous successes in Africa in this regard, where security cooperation has emerged as a key pillar of the China-Africa relationship that was dominated by economic issues until about 10 years ago. Wang Yi suggested as much when addressing counterparts in the Pacific, stating ‘We support not just South Pacific island countries, but also developing countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America.’

Initiatives such as the China-Africa Defence and Security Forum (2018), the China-Africa Peace and Security Forum (2019) and the China-Africa Security and Law Enforcement Forum not only remind of China’s aforementioned proposal in the context of cooperating with the Pacific Islands, but also reflect China’s willingness to establish non-Western, alternative institutional arrangements to discuss security-related topics with counterparts across the Global South. From Africa to the Southern Pacific, security has thus become a key tool to consolidate China’s diplomatic footprint.

Lei Yu

The realist theory of international relations concludes the security footprint of a state will be extended to where its interest exists and there is no exception to China in this regard.

What are the Chinese interests in the Pacific Islands? First of all, there are around 50,000 Chinese nationals living there, mainly from Fujian and Guangdong. Most of them are in possession of small businesses and are vulnerable to local riots. Some of them had been looted in the riots over the last decades. Danny Philip, former Solomon Islands prime minister, claimed that the Australian security forces deployed in Honiara to quell last November’s riots were instructed not to protect the local China town. This has led to increasing pressure from the overseas Chinese, around 60 million across the world, on the Chinese authorities to provide them with protection for their lives and properties.

China is in need of political support from developing states, including the Pacific Islands states, to block the US-headed West from interfering with its domestic affairs

Second, China has rapidly grown as one of the most significant economic players in the Pacific Islands and has shown a strong capacity to grow even further. Statistics released by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce shows that two-way trade skyrocketed to $8.2 billion in 2018 from $880 million in 2005 and China’s FDI reached $4.5 billion in the same year, up from 900 million in 2013. China views the Pacific Islands as a significant component of its “Belt and Road” initiative, which is an umbrella initiative, involving a massive amount of infrastructure construction and investment projects. China had signed BRI cooperation documents with 10 of the 14 Pacific Islands countries by 2021. The official Chinese data reveal Chinese investment in infrastructure projects has become the lion’s share of its investment in the region. Moreover, China displays strong interests in local fisheries and aquaculture with scores of Chinese enterprises having invested in the fisheries industry across the region.

Finally, the South Pacific has long been an arena for China and Taiwan to compete for diplomatic recognition and is the newest battleground in China-US geopolitics. The Chinese foreign policy elites view Taiwan as an “inseparable” part of China and accuse the United States of abetting Taiwan’s split to contain China. China is in need of political support from developing states, including the Pacific Islands states, to block the US-headed West from interfering with its domestic affairs, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, human right, etc.

To conclude, China’s efforts to increase its security footprint in the Pacific Islands is primarily driven by its own interests there, as other states have done in that region and elsewhere. China’s efforts reflect its sense of vulnerability in terms of protecting its overseas interests. However, it remains to be seen if this will develop into a part of China’s grand strategy. It is equally noteworthy the Pacific Islands welcome and embrace China’s presence as reflected by the comments made by Frank Bainimarama, Prime Minister of Fiji, and other political elites: China’s increasing presence is ‘a great leverage over the traditional powers’.

Asha Sundaramurthy

The visit of the Chinese Foreign Minister Wang to the Pacific Islands demonstrates a concerted move from Beijing to scale up the attention given to the region. A closer look into China’s driving interests can shed light on the potential shape of the future sub-regional order and illustrate the prospective value chain of a much-neglected regional market.

There are geostrategic drivers to Chinese interests in a region that was previously under the influence of the USA and its allies. The location of the Pacific Islands between Australia, Japan and the USA is of interest to China; with reports of Beijing trying to set up military bases in Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. China has also established security agreements in Tonga, and Solomon Islands by providing defence, police, and military training. In the recent visit by Minister Wang, Fiji also expressed interests to deepen its bilateral engagement while Samoa strengthened bilateral funds into infrastructure. There are also reports of China attempting to hone its Beidou navigation system by creating satellite centres in the region.

There are geostrategic drivers to Chinese interests in a region that was previously under the influence of the USA and its allies

China’s expanding global economic footprint has fostered interest in the Pacific Island states to participate in the global growth, with Tonga calling for the BRI to be extended to the region. Though the islands have small populations, and markets, Beijing has developed commercial interests stemming from the region’s large EEZs. There is also an abundance of maritime resources such as energy resources, fisheries, and critical minerals that makes this region a lucrative strategic investment.

China is arguably the largest aid donor in the region. Through several decades of Beijing’s chequebook diplomacy, there are only four Pacific Island states that recognise Taiwan today. While there are reports that China’s aid diplomacy is not as strong as it used to be, the reliance of these small territories to external aid from bigger powers is inescapable. The diversification of aid flows to emerging powers in recent decades have provided a degree of strategic autonomy to these island nations. These aid flows open the access to new technology, markets, commerce, and opportunities, however, opens the converse effects of excessive of external influence, which are over-exploitation of resources, excessive debt dependence and a destruction of ecology that can be detrimental to these island states. The island nations are also careful to ensure that the region does not become the site of great power contestation.

Though unclear if that is the cause, the plans of a region-wide security agreement between China and the South Pacific region have recently been shelved. Nevertheless, Beijing has responded with a statement reiterating its commitment to increasing its strategic partnership in the region through its draft of a Five Year plan that covers a wide array of sectors from politico-security, defence, climate change, capacity-building, health, and multilateral cooperation. China is very much a strong participant in the sub-regional order and the consequent competitiveness of aid donors has benefitted the region significantly, particularly for the small economies of the islands.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

The blog image, “People’s Armed Police squad 2“, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

A good write up. Maybe a follow up of the second base being eyed in the region by China will further buttress the thoughts expressed. AUKUS has its task cut out now and how would you predict the future ripostes by the pact to Chinese (mis)adventures in the region? Who is in a better position to shape opinions in the region?