The inequalities arising from homeschooling during lockdown will exacerbate existing inequalities in education, write Jake Anders (UCL), Lindsey Macmillan (UCL), Patrick Sturgis (LSE), and Gill Wyness (UCL). Their study uncovers deep divisions along the lines of gender and class when it comes to supporting children’s education during the COVID–19 lockdown.

The past few weeks have been challenging for parents across the country working hard to support their children to continue to learn during the COVID–19 lockdown. One of the reasons for the big push to get kids back to school is the concern over inequalities driven by differences in home learning. Using new data from a high-quality random sample collected using the Kantar Public Voice Survey, we examine the extent of inequalities in homeschooling during lockdown from the end of April to the beginning of June. They find stark differences between graduate and non-graduate parents in the time spent homeschooling. We also find parents differ in their perceptions of how well they are able to support their children’s learning, and in how the burden of homeschooling is divided between mothers and fathers.

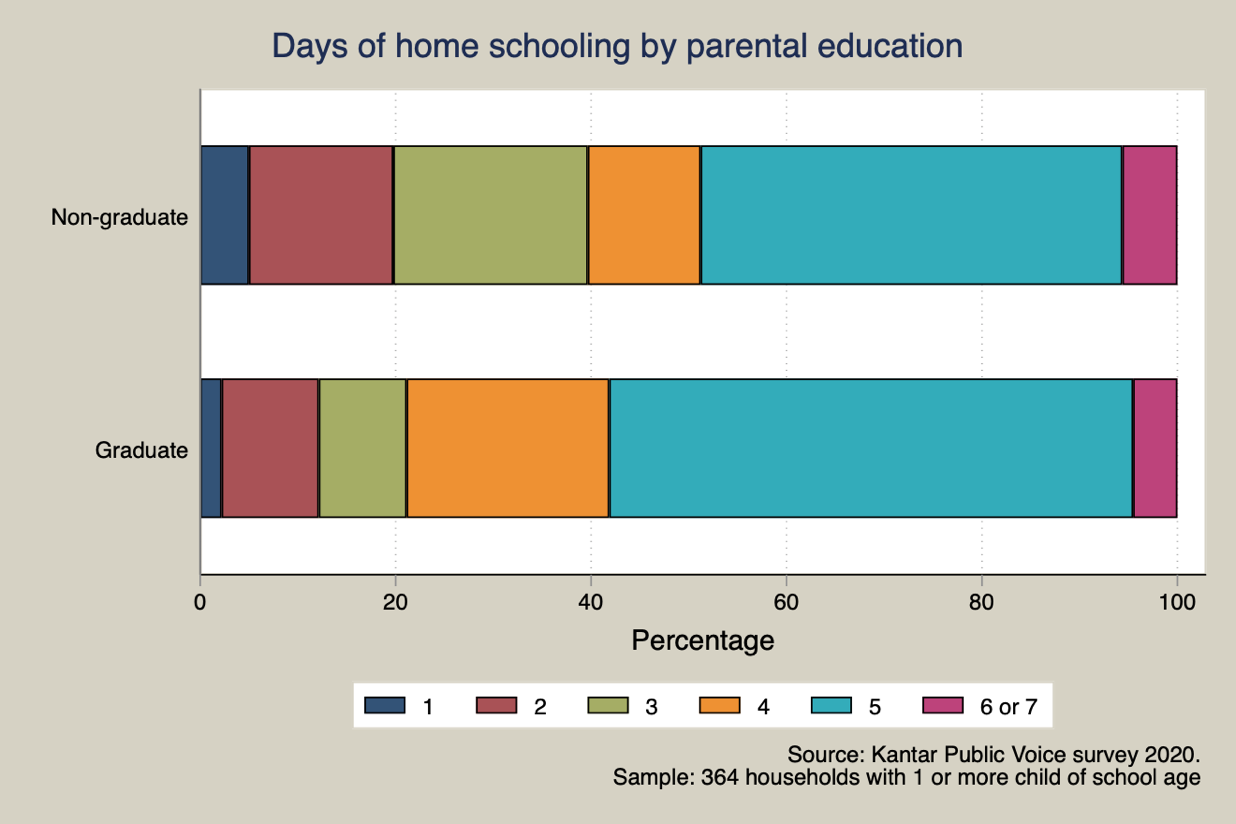

Differences in days spent homeschooling

While very similar proportions (around 75 per cent) of graduate and non-graduate parents report doing any homeschooling, graduate parents report homeschooling their children on more days per week compared to non-graduate parents. While almost 80 per cent of graduate parents home school their children at least 4 days a week, only 60 per cent of non-graduates are homeschooling this often. This is consistent with other surveys covering the same period that have found inequalities in the amount of time spent homeschooling by parental income.

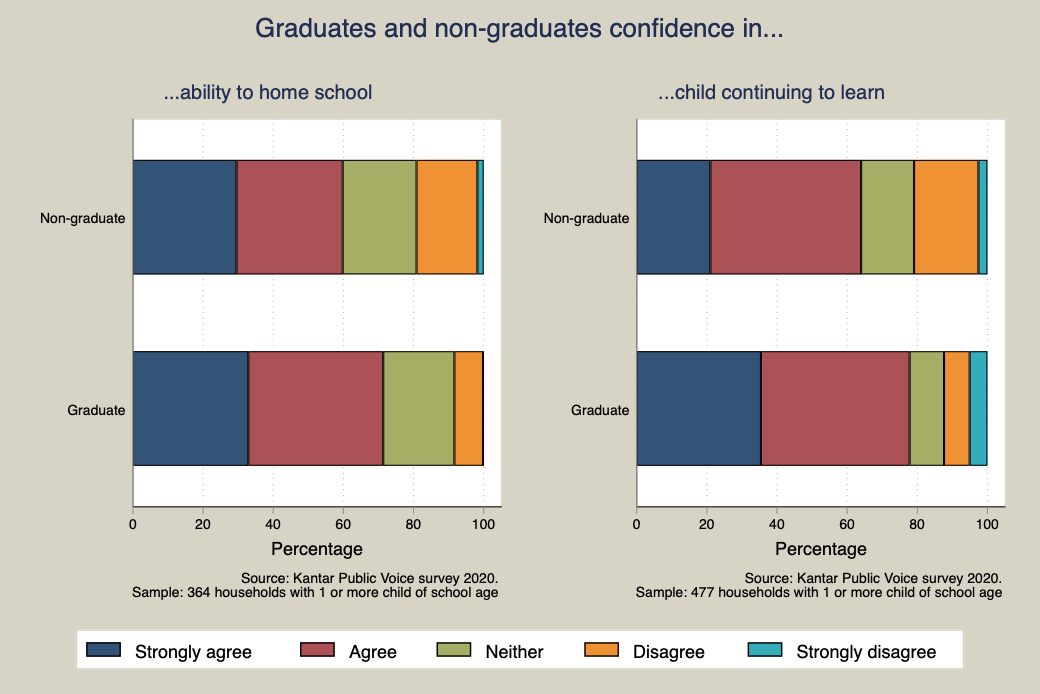

Differences in perception of ability to home school

These differences in time spent homeschooling could be driven, in part, by graduate parents being more confident in their ability to home school. For example, in our survey, graduate parents were more likely (70 per cent) to agree with the statement ‘I am confident in my household’s abilities to home school my child’ compared to non-graduates (60 per cent). Similarly, graduate parents report more confidence that their child’s learning is continuing. This confidence gap in the ability to home school is concerning, as studies show that children who have parents with anxiety about maths tend to perform worse in mathematics.

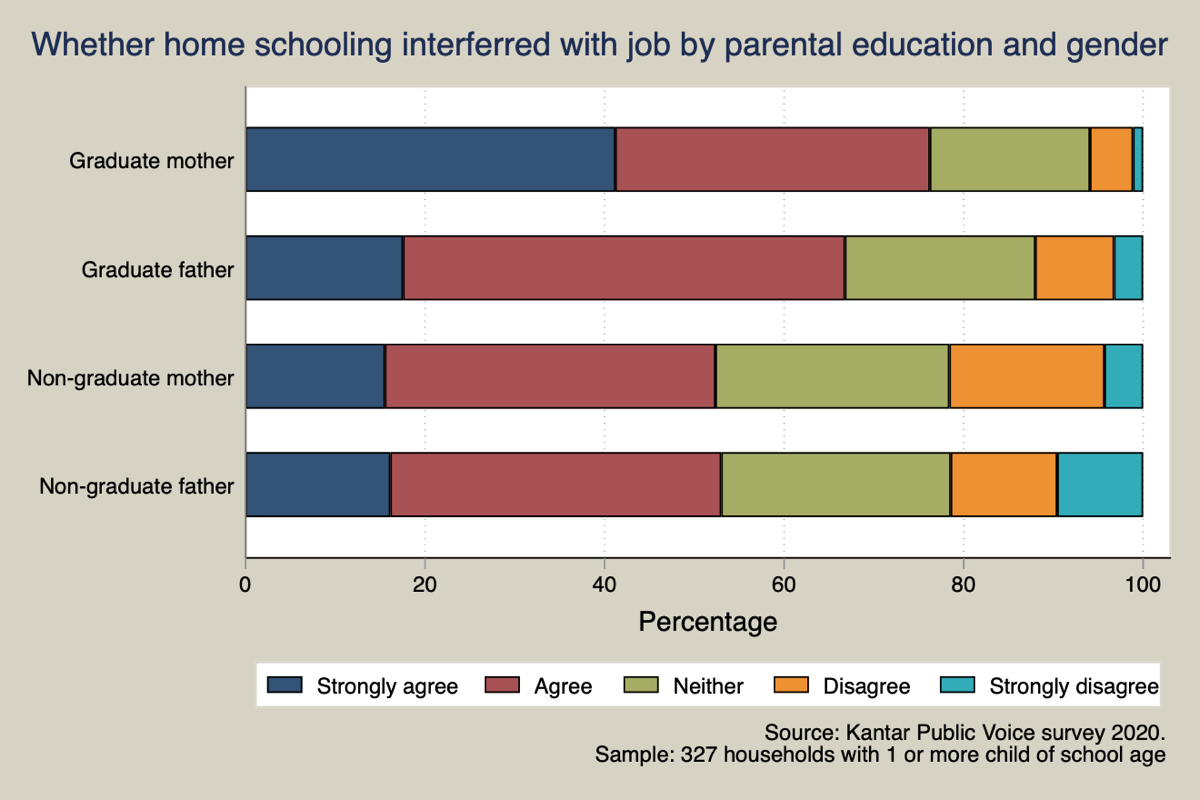

Differences in perceptions of interfering with their job

These differences in time spent on homeschooling seem to have a consequential effect on whether parents’ feel able to do their paid jobs. Graduates are substantially more likely to agree that homeschooling is interfering with their job, a difference that is particularly pronounced for mothers, with nearly 80 per cent of graduate mothers agreeing that homeschooling has interfered with their job, compared to 67 per cent of graduate fathers, and 50 per cent of all non-graduates.

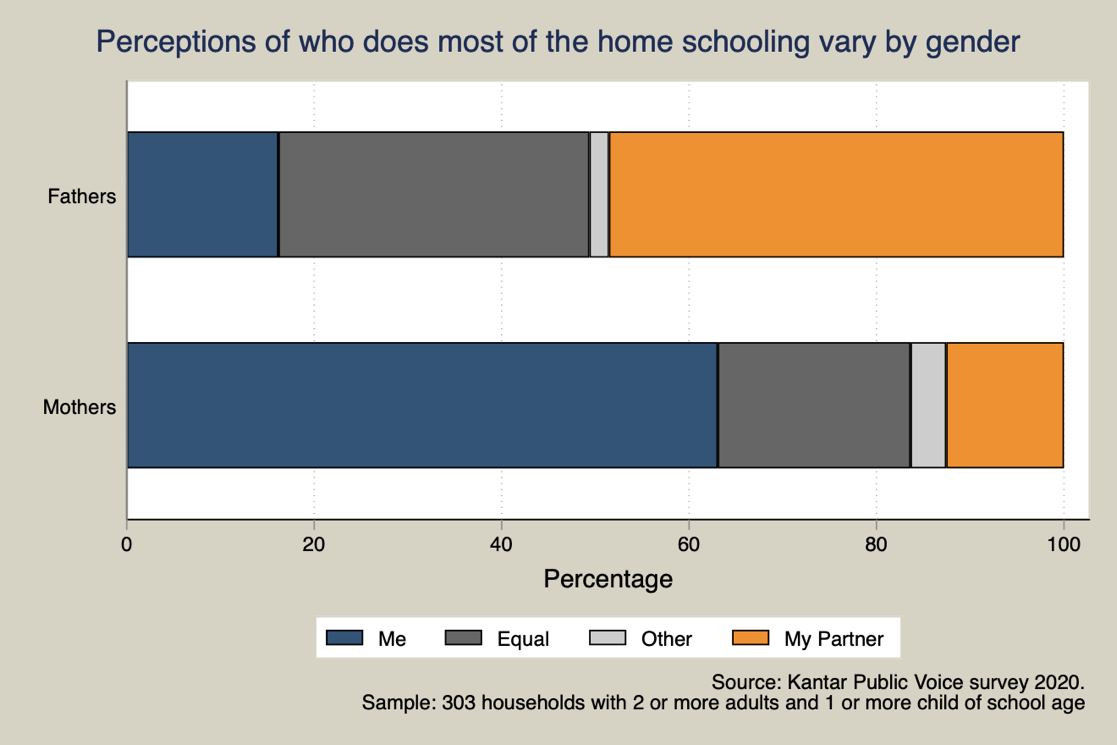

Differences in perception of who is doing the most homeschooling

This inequality between mothers and fathers can also be seen when we consider who is doing the most to support their child with schoolwork during lockdown. Around half (49 per cent) of fathers say that their partner does most of the homeschooling, with the other half split between those who say that they take on the lion’s share (16 per cent), and those reporting that this responsibility is shared equally (33 per cent). This contrasts with mothers, of whom almost two-thirds (63 per cent) say they devote most time to this task, one fifth (21 per cent) reporting an equal split, and just 13 per cent saying that their partners are doing the majority of home-schooling. These patterns are, again, particularly pronounced for graduate mothers. Similar differences in perceptions between mothers and fathers have also been found in the US, where 45 per cent of fathers said they did most of the homeschooling – but just 3 per cent of mothers reported that their partner was making the largest contribution.

Support for children and working mothers

Taken together this new evidence from a high-quality random sample of parents suggests that inequalities arising from homeschooling during lockdown will exacerbate existing inequalities in education. We know that children of graduate parents already have higher levels of cognitive and socio-emotional skills on school entry. These inequalities are only likely to widen if children from less advantaged backgrounds are spending less time on home-schooling during lockdown. Non-graduate parents are also less confident in their ability to home school their children and this may be detrimental to the quality of the support they are able to provide.

Our survey also reveals gender disparities in the impact of homeschooling, with graduate mothers particularly likely to report that homeschooling is interfering with their jobs. But parents perceptions do not align on who is sharing the greater burden; while half of fathers say they are doing at least an equal share, a clear majority of mothers think that this level of paternal input is exaggerated.

Catch up strategies when schools re-open should be mindful that returning children will have been exposed to different levels of homeschooling. Similarly, employers should be mindful that the burden of homeschooling during lockdown is more likely to have affected mothers compared to other employees, and factor this into future pay reviews and promotions.

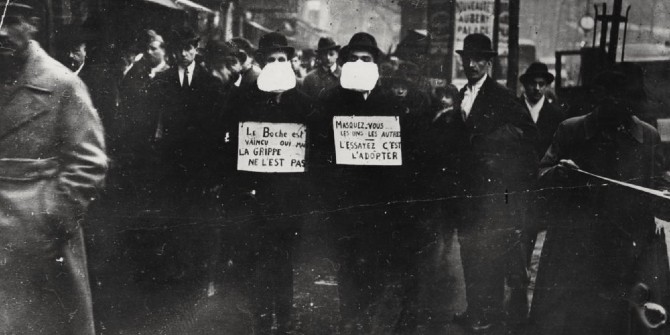

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog or LSE. Image: Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license.

3 Comments