Who breaks lockdown rules, ask Patrick Sturgis, Jonathan Jackson and Jouni Kuha (LSE)? In this blog, they discuss lockdown compliance and lockdown scepticism on the basis of evidence from a new random sample survey.

Interest in the question of who breaks lockdown rules has intensified since Dominic Cummings’ controversial trips to and around Durham in early April. Concern has been expressed widely that Mr Cummings’ highly visible breaking of the rules that he, and others at the top of government, imposed on others, may erode public compliance with social distancing and the track and trace system that will be key to controlling the virus until a vaccine is found.

Opinion polling has consistently shown the British public to be highly supportive of lockdown. Indeed, despite the prominence afforded to anti-lockdown protests in the media and the high profile of some of its leading advocates, the position may actually be one of the most fringe ever seen in British society, with just 5% opposing the extension of lockdown in mid-April. Comparative polling by Ipsos-MORI also found the UK to be amongst the most pro-lockdown countries internationally, with the strong national consensus seemingly unaffected by the partisan polarisation that has characterised public opinion on lockdown in the US.

Yet, though the position in the UK may not exactly mirror the polarised nature of the COVID-19 response in the US, there are reasons to believe that resistance to lockdown may be more widespread and ideologically patterned than a simple binary support/oppose question can reveal. While people may support the lockdown policy overall, they may nevertheless be quite sceptical about its net benefits.

Additionally, there are indications that lockdown scepticism is becoming increasingly entwined with the Leave/Remain divide that dominates most aspects of British politics. Many pro-Brexit Tory MPs are increasingly critical of the high costs of lockdown on individual freedoms and the economy and have been pushing, both publicly and privately, for easing of the restrictions. Meanwhile, political scientist Ben Ansell has found that the behaviour of people living in Remain-voting areas suggests they are complying more with social distancing rules compared to people in Leave-voting areas, even when accounting for differences in social and economic composition between areas.

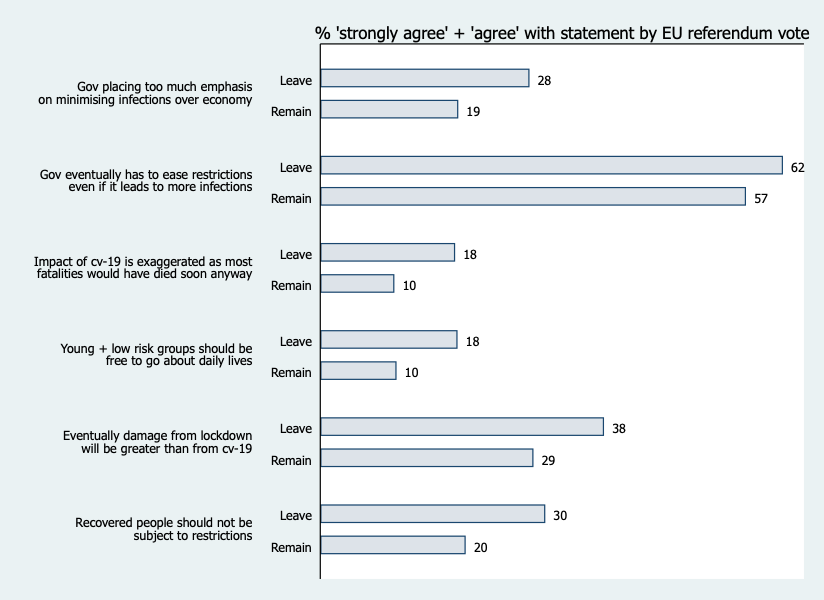

To get a better understanding of the factors underpinning lockdown scepticism and compliance, we ran a survey on the Kantar Public Voice probability panel, with 1840 interviews carried out online and on the phone[1] between 1st May and 1st June. To measure lockdown scepticism we asked respondents to state their level of agreement with six statements relating to different aspects of lockdown. These six statements, shown below, cover the balance between minimising infections vs damage to the economy, the concentration of fatalities amongst high-risk groups, and the non-COVID related impacts on health, well-being, and individual freedom:

- The government is placing too much emphasis on minimising infections from the coronavirus and not enough on keeping the economy going.

- The government will eventually have to ease restrictions on our daily lives, even if that leads to more people catching the coronavirus.

- The impact of the coronavirus is being exaggerated because most of the people dying would have died within a year or two anyway.

- Young people and other groups at low risk of serious illness from the coronavirus should be free to go about their normal daily lives.

- Eventually, the damage to people’s lives from the lockdown will be greater than the health problems and fatalities caused by the coronavirus.

- If you can prove you have recovered from the coronavirus, you should not be subject to restrictions on what you can do.

The figure below shows the percentage of the public who agree with each statement by whether people voted Leave or Remain in 2016. While only minorities agree with five of the six statements, these items reveal substantially more scepticism about the net benefits of lockdown than a binary support ‘yes/no’ question. We can also see that, on all six items, Leave voters are more sceptical about the benefits of lockdown than Remain voters, though this may, of course, be due to other demographic and attitudinal differences between these groups.  To check this, we combined the six items into a ‘lockdown scepticism’ scale, and included a range of other potentially relevant predictors of lockdown scepticism in a regression model predicting an individual’s degree of lockdown scepticism. The figure below shows the results of this analysis graphically. The ‘effect’ of each variable (listed on the vertical axis) on lockdown scepticism is shown as a blue circle, with circles further to the right of the chart indicating more lockdown scepticism. The uncertainty due to sampling variability, the ‘margin of error’, is indicated by the lines emanating right and left of the circle. If the margin of error crosses the red line that runs vertically from zero on the horizontal axis, we conclude that there is no significant effect of the variable on lockdown scepticism.

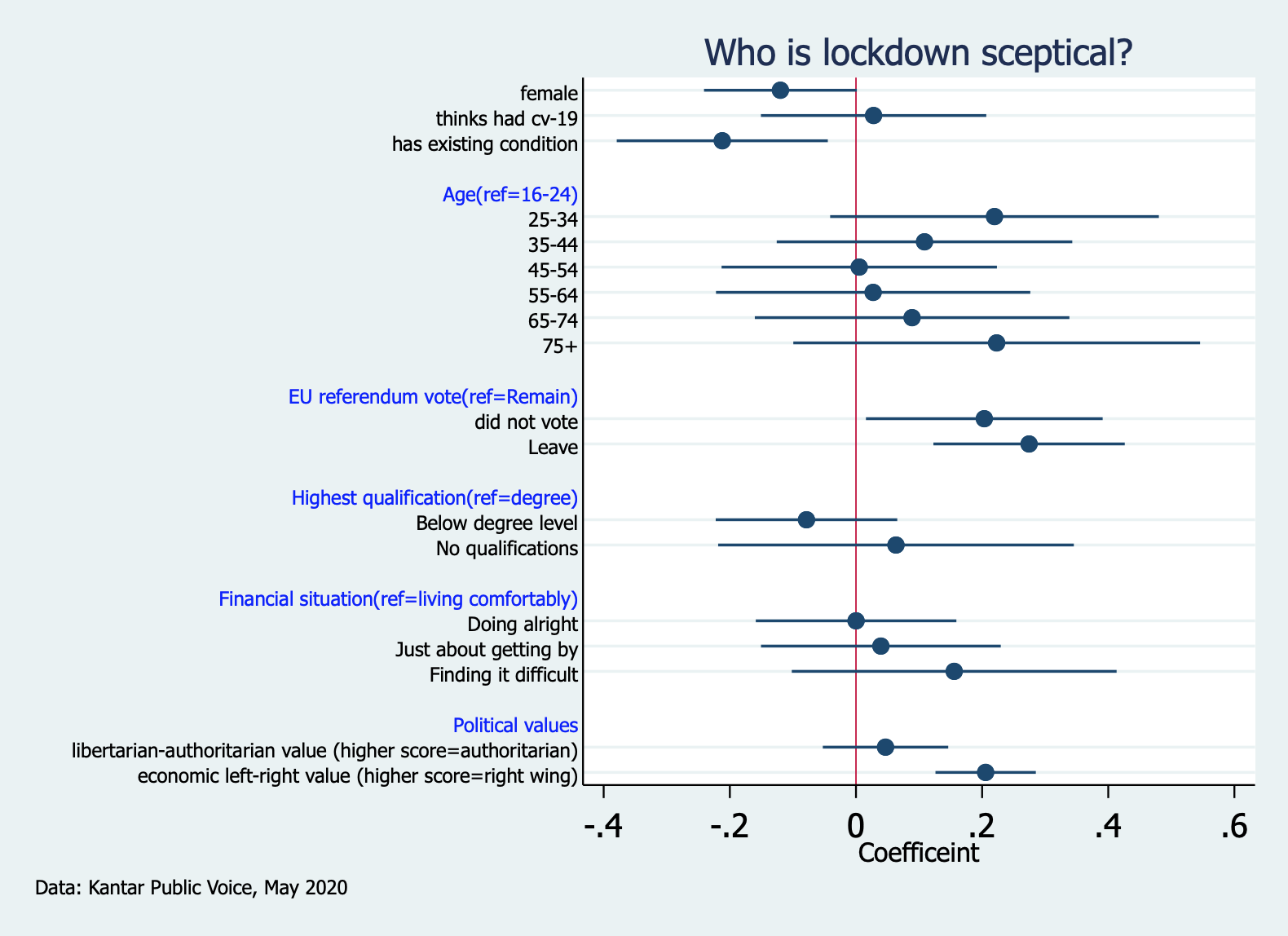

To check this, we combined the six items into a ‘lockdown scepticism’ scale, and included a range of other potentially relevant predictors of lockdown scepticism in a regression model predicting an individual’s degree of lockdown scepticism. The figure below shows the results of this analysis graphically. The ‘effect’ of each variable (listed on the vertical axis) on lockdown scepticism is shown as a blue circle, with circles further to the right of the chart indicating more lockdown scepticism. The uncertainty due to sampling variability, the ‘margin of error’, is indicated by the lines emanating right and left of the circle. If the margin of error crosses the red line that runs vertically from zero on the horizontal axis, we conclude that there is no significant effect of the variable on lockdown scepticism.

Women and people with an existing condition are less sceptical of lockdown but there is no difference in lockdown scepticism by age, education, or perceived financial situation. Likewise, people who think they have already had coronavirus are no more lockdown sceptical than those who have not.

However, the Brexit divide is still apparent, even controlling for these other characteristics, with Leavers and those who did not vote in the referendum significantly more lockdown sceptic than Remainers. In terms of core political values, there is no difference in lockdown scepticism by where people fall on the libertarian-authoritarian dimension but people who are more right-wing economically are more sceptical of lockdown. This suggests, unsurprisingly perhaps, that a key driver of lockdown scepticism is concern about the substantial damage to jobs and businesses and the unprecedented state intervention to support the economy.

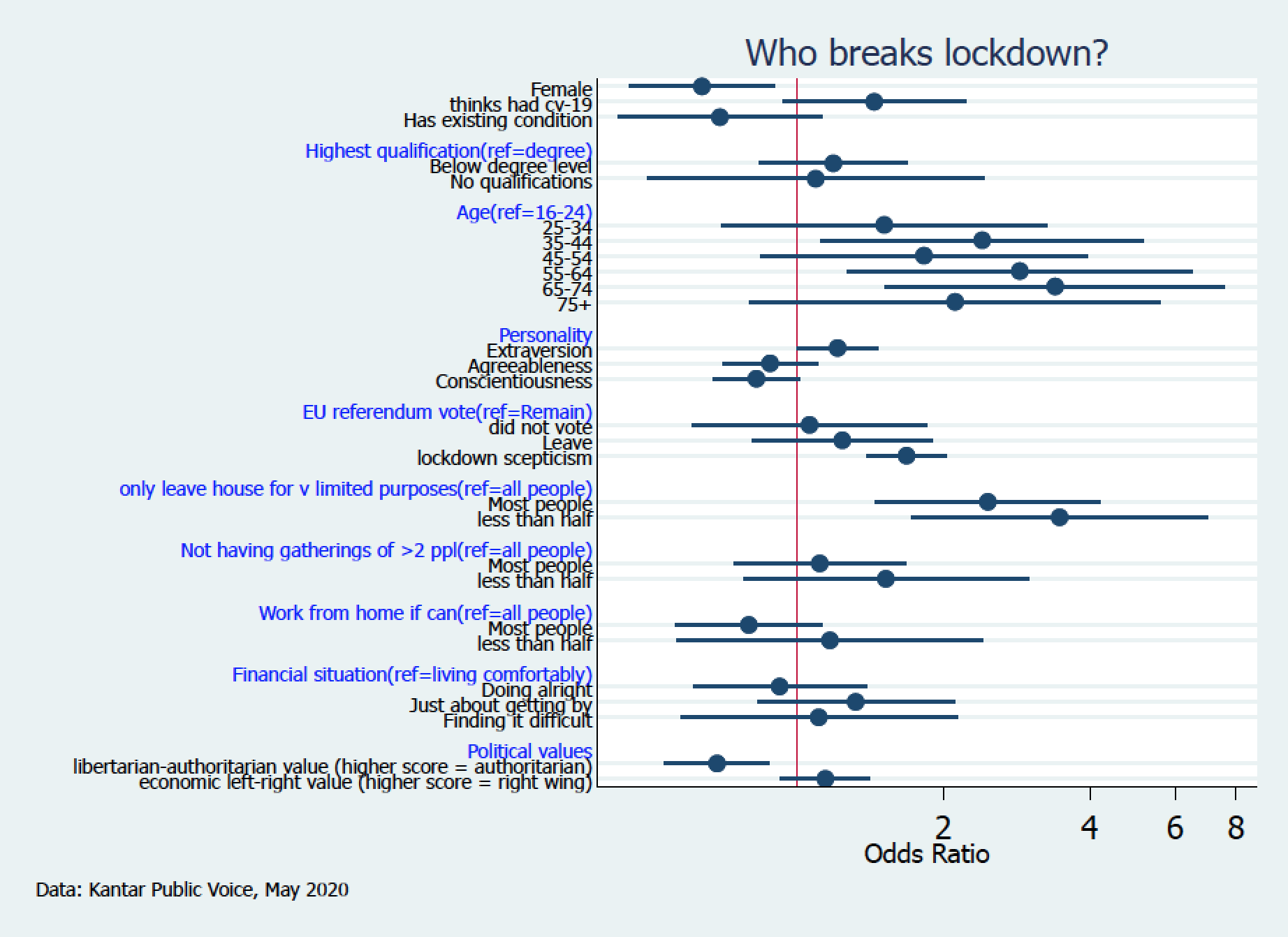

Next, we turn to a consideration of actual compliance with the rules of lockdown. We first asked respondents to tell us what proportion of the public (‘nearly all’, ‘most people’, or ‘less than half of people’) are complying with three key pillars of lockdown: only leaving the house for very limited purposes; not having gatherings of more than two people; and working from home if you can. We then asked respondents to rate the extent to which they themselves have been complying with lockdown. This showed that nearly a third (29 per cent) of the public reported not sticking to the lockdown guidelines completely, although less than 1 per cent reported sticking to the guidelines ‘not very much’, or ‘not at all’. We fitted a second regression model, this time predicting the probability that someone reported breaking lockdown guidelines, with the results presented graphically below.

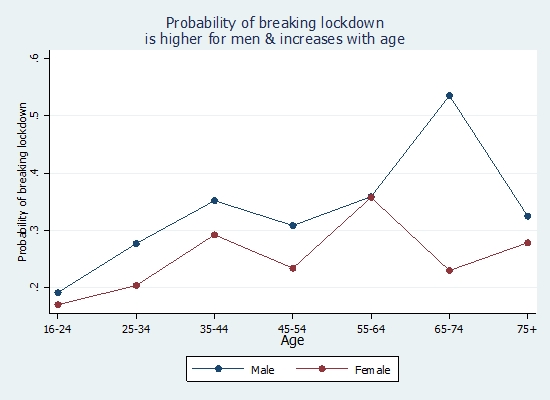

Women were less likely to report breaking lockdown, as were people in younger age categories. This somewhat counterintuitive finding about the age gradient can be seen more clearly in the figure below, which plots the probability of breaking lockdown by age and sex. Men are more likely to break lockdown in all age groups with the group least likely to comply being men aged 64-75, of whom more than half report having not stuck to the guidelines completely. While other studies have found that young men have lower levels of compliance and are most likely to be fined by the police, we find that it is older men who are the least compliant.

There is no significant difference in the probability of lockdown violation according to educational level, whether people have an existing medical condition, people’s financial situation, or by whether people think they have already had COVID-19. In terms of personality, extroverts are more likely to break lockdown, while people high on conscientiousness and agreeableness are less likely to do so, though the effects for conscientiousness and agreeableness are not statistically significant.

For political values, we find a different pattern for lockdown violation than for lockdown scepticism. There is no difference in lockdown compliance according to the economic left-right dimension but people who are higher on the authoritarian dimension are less likely to break lockdown, likely a result of the high value placed on obedience and respect for authority in the authoritarian worldview.

Social norms also seem to play an important role – people who think that others are not complying with lockdown are more likely to break lockdown themselves, although this only seems to matter if people think that others are leaving their homes for more than very limited purposes. People who think that others are not sticking to this rule are substantially more likely to report breaking lockdown themselves. This suggests that Dominic Cummings’ highly visible breaking of the ‘stay at home’ rule may well serve to reduce public compliance in the future.

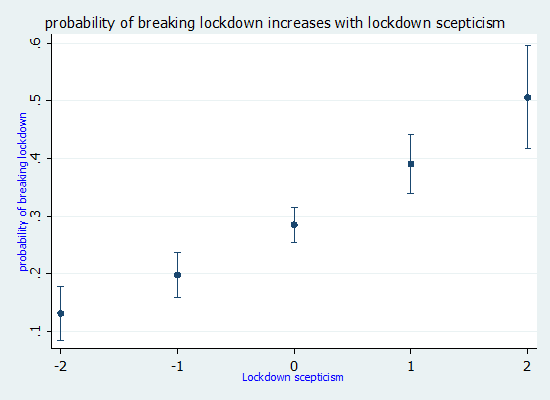

Finally, we find no difference in lockdown compliance according to people’s EU referendum vote, although there is a strong relationship between lockdown scepticism and violation of the lockdown guidelines, which can be seen in the figure below. Over 50% of people who score highest on lockdown scepticism report having broken lockdown compared to around 13% of those with the lowest levels of scepticism.

So, while we find no direct effect of EU referendum vote on breaking lockdown, there may be an indirect effect of the Brexit divide through the channel of lockdown scepticism, an idea that we intend to pursue in future research. In any event, it seems that, alongside high overall support for lockdown, there is a strong streak of scepticism at large in public opinion about its net benefits. It would not be surprising if this scepticism were to deepen as fatigue with lockdown and its wider consequences is felt ever more keenly in the weeks and months ahead.

[1] 95% of interviews were online self-completion and 5% were carried out by phone.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog or LSE. Photo © Nick Mutton (cc-by-sa/2.0).

I complied with the lockdown rules, but I do not supported them. The evidence is clear-cut that they make little to no difference. You can see that not resorting to them in Japan, Belarus, Taiwan, Iceland and Sweden did not lead to huge rates of death. You can also see from Belgium, Spain, France, UK, Italy and America that imposing them did not prevent deaths. The fact that some countries had lockdowns and low death rates does not prove their effectiveness because countries that did not follow them also have low rates of death. I am now completely apolitical and shocked that people are still trying to explain “lockdown scepticism” in political terms rather than looking at the reality that there is no evidence they actually worked. That is more significant than the politics of who was saying what.

There is overwhelming evidence that lockdown works – where are you getting your information from?. For example Sweden had the highest infection rates in Europe, and adopted some lock down measures in the end.

I don’t understand the age category results which have for each group greater scepticism and more breaching of the rules.