More flexible business regulation encourages both the development of startups and the inflow of foreign investment, write Simeon Djankov (LSE), Dorina Georgieva and Hibret Maemir (World Bank).

Fiscal crises such as the one spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic motivate regulatory reform, which in turn can speed up the economic recovery. Past evidence suggests that this acceleration takes place through two main channels: new local entrepreneurship and increased foreign direct investment (FDI).

Entrepreneurship is critical for the continued dynamism of the modern economy, as forcefully argued by Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter in deriving his theory of creative destruction. Startups make economies grow faster – as a source of innovation and new jobs. The business environment needs to be conducive to growth for new businesses to be born in the first place, to get a “birth certificate” (formal registration with the authorities) and subsequently expand.

When faced with costly regulations, startups lose the freedom to innovate and grow their business efficiently, often opting to stay informal. Friedrich Hayek, one of LSE’s many Nobel Prize winners in economics, is best-known for promoting such freedom. Informal firms are less productive and can erode formal firms’ market share and societal resources available to boost productivity, which slows down economic growth.

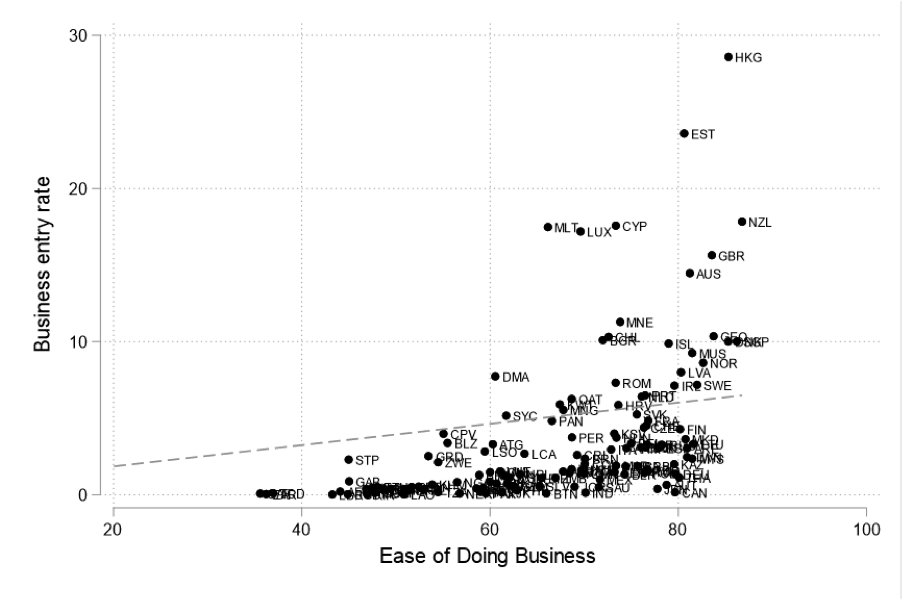

The global analysis illustrates that countries with easier business regulatory processes tend to inspire more new business creation (Figure 1). This finding mirrors a recent study using panel data for 10 years across more than 180 economies which finds that an improvement of 10 points in the overall measure for business regulations is linked to an increase of 50 new businesses per 100,000 adults. To put this estimate in perspective, hypothetically it would mean an additional 26,000 new businesses in the United Kingdom each year.

A hypothetical improvement in business regulations from lowest quartile to highest quartile of countries globally is associated with a 0.8 percentage point increase in annual per capita growth. Again, to put this estimate into perspective, it hypothetically implies an additional £18bn of GDP growth in the United Kingdom in 2019, a sizable effect. Conversely, costly regulations hamper the creation of new firms, especially in industries that should have high entry.

Figure 1: Economies with a more conducive business environment have more startups

Source: World Bank’s Doing Business and Entrepreneurship databases. Note: The relationship is significant at the 1% level. The sample includes 135 economies.

Over the last 15 years, governments around the world have implemented more than 3,800 business regulatory reforms in an effort to facilitate new businesses. This reform dynamism ought to accelerate after the health crisis is over. Along with the more traditional tools of eliminating minimum capital requirement, reducing time and cost for business incorporation or property transfer procedures, new digital solutions are emerging that further ease the entry of “recovery entrepreneurs” and property registration for new real estate owners.

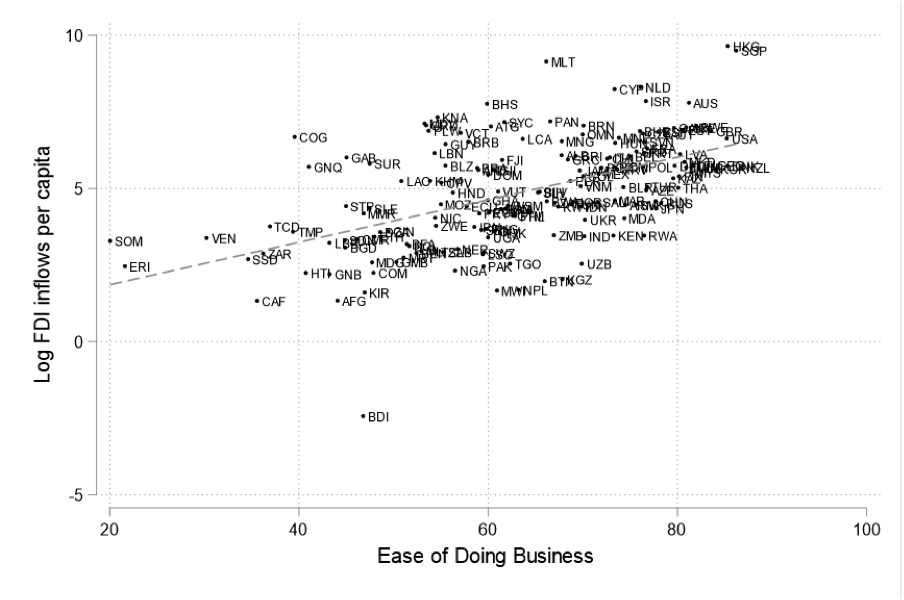

Improving the business regulatory environment brings benefits to domestic firms but also influences foreign investors to stay or enter a market (figure 2).

Figure 2: Economies with a better business environment attract more FDI

Source: World Bank’s Doing Business and World Development Indicators databases. Note: The relationship is significant at the 1% level. The sample includes 170 economies.

Using the latest data on FDI inflows, we find suggestive evidence that the size of FDI inflows per capita is larger in economies with more flexible business regulations. This finding is supported by previous literature too. This association is important – in particular – for emerging markets and developing economies which suffered unseen capital outflows since the beginning of the pandemic crisis. The task of rebuilding investors’ confidence is more challenging than ever. FDI is a critical source of external finance, creating jobs and raising productivity (through new capital and technologies) thereby improving household incomes and lifting people out of poverty.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It first appeared at the LSE Business Review blog.