People are keen to find out about the latest scientific work on the pandemic – but they do not always understand that research is a slow process and the findings can only be provisional. Zubeyde Demircioğlu (Istanbul Medeniyet University) says public frustration will lead to a distrust and a surge in conspiracy theories unless scientists are clear that, at this early stage, much remains uncertain.

In uncertain times like pandemics, people want to access information quickly so they can interpret the confusing situation around them. Access to information is no longer a significant problem with the development of communication technologies, but its accuracy and reliability is. COVID-19 has spawned both a pandemic and an “infodemic” of hoaxes, conspiracy theories, misunderstandings, and politicised scientific debates.

The World Health Organization (WHO) explains that “infodemics” are caused by an excessive amount of information surrounding a problem, making it difficult to identify a solution. This mixture of misinformation, disinformation, and rumours around coronavirus has exploded online. Despite the efforts of Facebook, Twitter and Google to combat dubious information, it seems impossible to prevent misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories completely. Aside from deliberate disinformation spreading widely across social media, the persistent scientific uncertainty—as the best information (and the scientific consensus) changes from day to day—has also diminished trust in science.

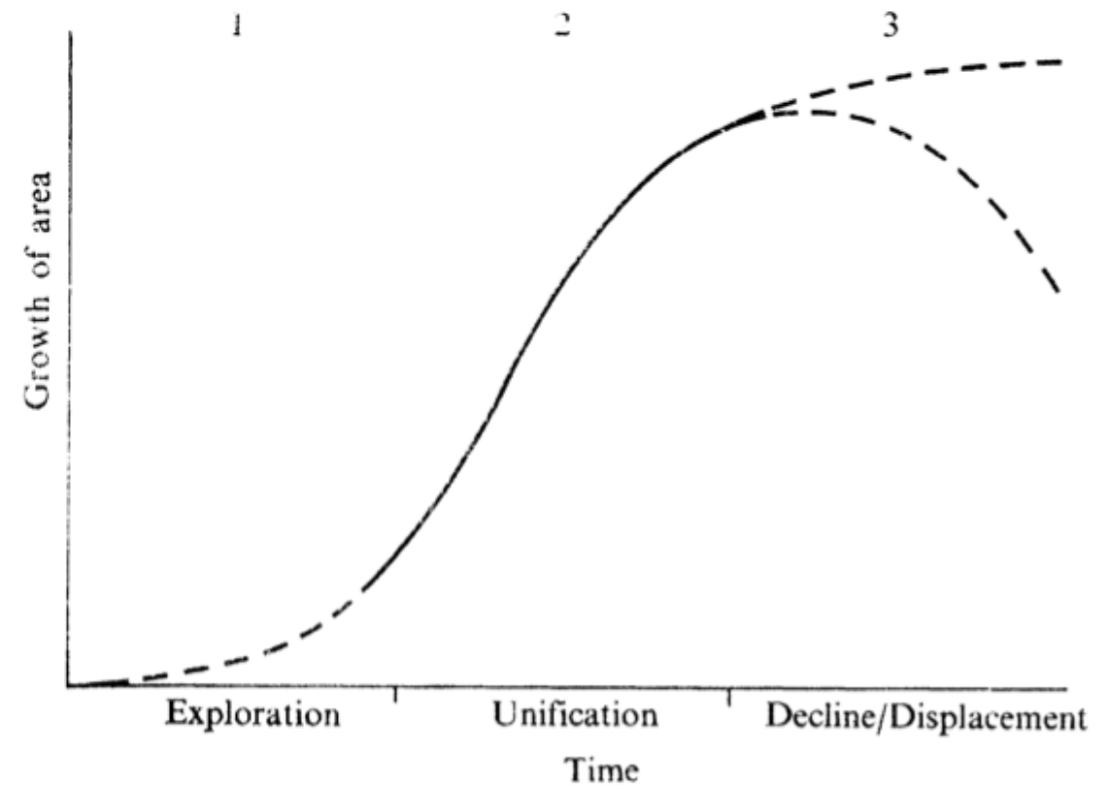

One of the issues that determine uncertainty and risk perception in laypeople is conflicting scientific data. Looking again at a model by M J Mulkay et al. (1975) can shed light on why this is currently so frustrating. His model, which attempts to explain the growth of scientific research areas, identifies three main stages in the growth of a research area: exploration, unification, and decline/displacement. These stages are shown in Figure 1, representing an idealised growth curve.

During the exploration stage, scientists are unlikely to have a clear conception of the research area to which they contribute. That conception only occurs after a considerable degree of scientific consensus has been achieved. Therefore, it is only possible to determine the growth of the exploration stage retrospectively.

Figure 1: Stage in the growth of research area [Mulkay, M. J., Gilbert, G. N., & Woolgar, S. (1975). Problem Areas and Research Networks in Science. Sociology, 9(2), p. 192.]

In the exploratory stage, there is little communication between those contributing, so the variables and the techniques tend to be obvious and discoveries and results can multiply. This is approximately what happened in the pandemic. Research on the coronavirus, which erupted suddenly with little scientific data available, is still in the discovery phase, so it is likely to be making many and various predictions.

Then, by explaining the initial results – widely dispersed among journals – the researchers make contact with each other and gradually enable the creation of a scientific consensus. This process can be seen as a negotiation between researchers. In many cases, as a result of negotiation, it is possible to agree on problems, variables, and techniques. Ordinarily, scientific knowledge is disseminated within the research community through formal publications in scientific journals, discussions at conferences, and collaborations in the laboratory. However, during the pandemic, scientific debates that typically play out over months are expected to conclude in the space of days, in public view. In addition, the control mechanisms in scientific publications have weakened with the impetus to produce scientific knowledge fast, and the reliability of the publications has become controversial.

Mulkay et al. (1975: 197) argue that one factor that will hasten the growth rate of research activities is an external audience that finds the new results valuable. It would be fair to say that this has accelerated much faster for the pandemic, where a critical audience constantly follows the latest scientific developments.

Another issue is sharing scientific knowledge. During the normal scientific study period, scientists who are used to interacting with only their peers are amassing followers on social media. Consequently, there have been transformations in both the debate platform and scientific language.

Establishing scientific consensus is a cumulative process, and not unproblematic. It also causes conflicts among members of the scientific community, and these have already arisen during the pandemic. As the problems become more clearly defined, researchers will focus on narrower, more specific topics, and the problem area will expand. This phase of COVID-19 has not yet begun.

The public demands immediate, absolute information – but science moves more slowly. If the public cannot evaluate scientific warnings correctly, conspiracy theories will take their place. Scientists should be as clear as possible when they communicate to the public; the uncertainties and weaknesses of studies should be clearly explained. Similarly, people and journalists should recognise that scientific studies, especially in a fast-moving situation like this, are provisional.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments