During the lockdown, Germans of all income levels stayed at home. But what happened once it was lifted? Amanda Driscoll (Florida State University), Jay Krehbiel (West Virginia University) and Michael Nelson (The Pennsylvania State University) discuss a study that finds people on lower incomes are much more likely to be exposed to the risk of catching COVID-19.

With lockdowns and stay-at-home orders expired (or expiring) around the world, who is staying home and who is going out? This is a question with important implications, because citizens who are forced to venture out into the world for work face significant health risks, dodged by others who can stay at home in self-isolation. We set out to address this question by considering one of the most powerful predictors of individuals’ experience of the pandemic: socioeconomic status.

Socioeconomic status has dramatically shaped the options for responding to the coronavirus crisis. While lockdowns forced most people to stay at home regardless of income, significant differences in behaviour arose as governments eased restrictions. White-collar workers who transitioned to working remotely could often continue to do so, and relied on grocery delivery and related services to ease the burden of sheltering in place. In contrast, blue-collar and service industry workers, whose work is impossible to complete remotely, have been forced to make a difficult choice between going to work and risking infection. Both anecdotal and systematic evidence suggests that this divergence in the demands of everyday life has contributed to the class-based disparities in infection and death rates found around the world.

To evaluate this shift in individuals’ behaviour after the end of lockdowns, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of 4,400 Germans in late April and early May as part of a study funded by the National Science Foundation. In March, along with much of Europe, Germany implemented significant restrictions on citizens’ daily life, including the closure of restaurants and bans on gatherings of more than two people. While the German government’s response has been widely praised for limiting the severity of the pandemic, outbreaks in lower income districts since the easing of restrictions on 3 May have highlighted how the experience of lower wage workers has the potential to differ significantly from that of wealthier Germans.

While we are not the first to examine the connection between class and movement during the pandemic, our survey has two critical advantages. First, we asked respondents to estimate how many hours they spent outside their home both before the onset of the coronavirus crisis and during the week they completed the survey. This provides us with individual-level data on both movement and the key political and socioeconomic attributes expected to help explain variation in respondents’ time outside the house.

Second, our survey was in the field both before and after the expiration of the German government’s restrictions on 3 May. About 20% of our respondents were surveyed while the federal order was in place, with the remaining 80% having completed the survey after the restrictions were lifted. When respondents took our survey was effectively random, so this split in our data means we can make comparisons between these two groups to see how the German government’s lockdown restrictions affected the relationship between socioeconomic status and staying at home.

To evaluate the effect of the lockdown policy, we first calculated the difference between the number of hours spent outside the home per week prior to the pandemic, and that number for the week in which the respondent took the survey. Unsurprisingly, the majority of respondents reported either little change or a decrease in the number of hours spent outside their homes since the pandemic began, with the average respondent saying they spent nearly 20 fewer hours away from home compared to a typical week before the pandemic.

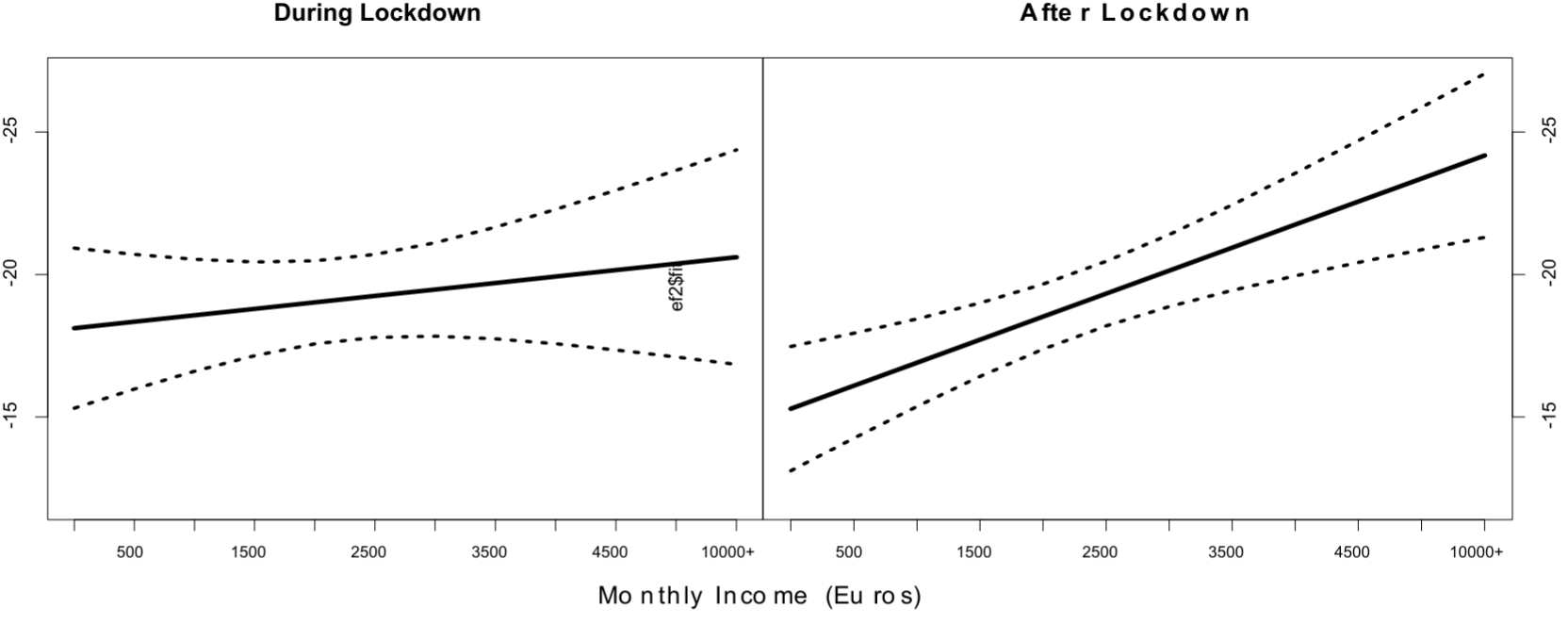

But what happens when we account for respondents’ income and whether the national restrictions were still in place at the time they took the survey? To see this, we plotted the change in hours spent outside compared to income for those responding before and after the German federal government’s restrictions expired. This revealed two trends.

Figure 1: Change in number of hours per week outside the home since the onset of COVID-19

Dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals.

Dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals.

First, income did not predict time spent outside the home while the restrictions were in force. Rather, the government’s order appears to have been effective at ensuring Germans of all income classes stayed home. This buy-in across society, which may in part have been a result of Germany’s generous social safety net programmes, likely contributed to Germany’s success in limiting the virus’s spread in the early months of the pandemic.

A different pattern emerges when we consider those who were interviewed after the restrictions expired on 3 May. Income emerges as a statistical predictor of time spent outside the home, with lower income respondents spending more time outside their homes. In contrast, those with higher incomes spent even less time outside than they had under the restrictions. Notably, this relationship remains even after accounting for other potential explanations like age, gender, partisanship, which state respondents live in and whether they live in an urban or rural area.

This divergence in behaviour is most noticeable when comparing the two ends of the socioeconomic ladder. Compared to the highest earners (over 10,000 EUR per month), low income respondents (less than 500 EUR per month) spent over nine hours more, on average, outside their homes after the German government lifted restrictions. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that many of the highest profile recent outbreaks in Germany have been linked to low wage workers in the agricultural sector, particularly meat packing plants.

We think these findings can help us understand how socioeconomic status interacts with governments’ policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Restrictions like lockdowns and stay-at-home orders may be able to mitigate differences based on wealth, although we suspect this may only be true insofar as lower income workers are supported by the state in exchange for their compliance.

It is when these orders are lifted, however, that the discrepancy between the haves and have-nots comes to the fore, often with serious consequences. The reinstatement of lockdowns in places like the German city of Gütersloh and the Australian city of Melbourne were the result of outbreaks originating among low wage workers who had little option but to return to work, despite the risk of infection. As such outbreaks continue to be the new front in the fight against COVID-19, we’ll likely see socioeconomic factors play a greater and greater role in determining how societies and communities experience this pandemic differently.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. SES-2027653, SES-2027664 & SES-2027671. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation, nor LSE.