In November, the Hull Daily Mail reported on a peak in local infections, restrictions on gatherings and school closures – but the year was 1918. In recent weeks, BBC Look North has been offering a rather more critical local perspective. Andrew Jackson (Bishop Grosseteste University) on the invaluable insight that local media offer during a pandemic.

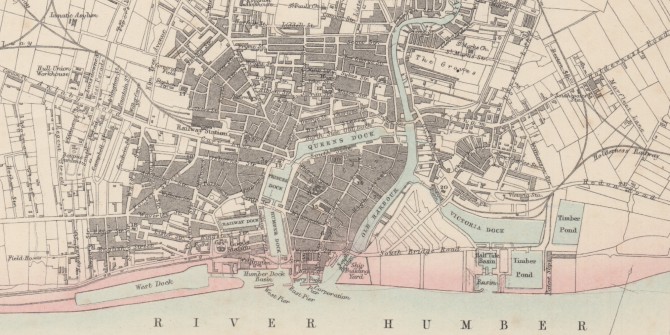

In mid-November, COVID-19 moved east. On Friday 13th, BBC Look North broadcast live from outside Hull Royal Infirmary, where the city had just finished the week in the ‘top spot’ in the country, with a rate of 743 COVID-19 infections per 100,000. North-East Lincolnshire, meanwhile, which includes Grimsby, had just taken second place at 587. Across the wider region, all local authority districts were recording infection levels higher that of England as a whole (196). 150 patients had been admitted to the Infirmary with COVID. “It is relentless”, said an NHS Trust medical director. “We are putting in a reserve plan that which will take us up to 800 if we need to, and I hope we never get to that point,” added the CEO for Hull Hospitals.

In November 1918, the provincial media coverage was similarly engaged with the latest data. The Hull Daily Mail was tracking the impact of the ‘Spanish Flu’, with the publication running a regular ‘influenza’ column. Readers were kept informed through ‘league’ tables of death statistics. On 7 November, the paper recorded that weekly influenza fatalities had peaked at 220. The newspaper also featured notices on the tightening up or loosening of various public health measures: personal hygiene recommendations, the cancellation of events and gatherings, the closure of schools and other buildings, or other municipal action such as the rationing of fuel and food essentials.

Throughout the 2020 pandemic, the provincial media has raised its profile and proven its worth. It has been especially welcome as a critical companion and counter to national or metropolitan viewpoints. National policy has been variously amplified, interrogated, or challenged, informed by the provincial media’s sensitivity towards its home patches and the communities, families and individuals represented. Objective reporting is customarily blended with the subjective and the emotive. A despairing viewer, ‘Jane’, wrote in to Look North: “I am fed up with people moaning about this virus. I lost my dad on 24 April from coronavirus-related pneumonia, and I have now lost my husband from the same thing. People are not taking it seriously and not wearing a mask … There’s a vaccine to come, but it’s come too late.” Columns from 1918 contain tragic tales as well: losses across generations of a family, the death of a veteran of the trenches, and public inquests on suicides among those affected.

In the week ending 13 November 2020, and in the one that followed, the programme covered the second wave in ever greater detail and broadcast speculative reasons for the upsurge. Was it, and not exclusively: complacency and weariness; confusion over complex and changing directives; a pre-lockdown spate of gatherings, together with a final rush to the coast; the opening of non-essential retail; lack of enforcement; desperation to travel to, and retain, jobs and livelihoods; transmission along the Humber estuary and eastern coastal strip corridor; or the ill-preparedness of the community, a legacy of Hull’s thankful escape from experiencing a severe outbreak during the spring wave?

Look North placed particular focus on official data, public policy measures and their timing, and corresponding public attitudes and behaviour. The programme lent further weight to representations from the Leader of the City Council and local MPs to the prime minister and Westminster, questioning the viability and credibility of central government’s insistence that schools remain open. Where, the programme asked, were the special measures and supports granted to Liverpool and Nottingham at moments during the tiered phase when their infection levels were far lower than Hull’s? The narrative of Hull as ‘the forgotten city’ was spun anew. Should Christmas be cancelled, Look North asked viewers at one point? Respondents favouring this course of action found themselves in the majority as rates of infection grew.

The Hull Daily Mail in 1918-19, like the provincial media today, at different times endorsed, communicated and augmented the state policy message. Local mortality rates were considerably in excess of those of 2020. In 1918, the final months of the First World War were preoccupying Britons. There were also censorship rules and practices that focused on topics likely to test the morale of the population further. Understanding of virology, and how to respond to a pandemic in medical or public health terms, was far weaker. Hull’s Mail gave the ‘Spanish Flu’ more attention than many other comparable publications, but the scale of the coverage was far less extensive than it is today, and it is more difficult to identify a sense of the regional media posing questions or critiquing measures, or the views and feelings of individuals and communities.

Critical opinion in the media or among readers in 1918 tends to be implicit, or can only be discerned indirectly. There are occasional comments of a more explicit nature on the effectiveness of the policy steps being taken by the state and how well public behaviour was attuning, or not, but these are relatively rare. Among the more vehement came in the words of a correspondent to the Mail on 29 November: ‘It is time that the public were taught that by spitting on the floors and by personal uncleanliness, they are the worst enemies of a well-ordered and healthy community, and, at the same time, the most powerful mediums of the spreading of diseases’.

Still, the press had plenty to cover. During the 1918-19 pandemic lockdowns were largely left to the discretion of district-level officials, primarily through the Medical Officers of Health – the Regional Directors of Health of their day. The actions and orders of the local MoH were closely followed in the provincial press. This level of delegation, however, would diminish. The second wave of the pandemic contributed to the formation of a Ministry of Health, and, in so doing, opened up a clearer way forwards towards the creation of a National Health Service.

For historians of the ‘Spanish Flu’, COVID-19, or both, the provincial media is an essential reference point for exploring the contemporary impact of pandemics. It is a source that gives a sense of the day-to-day, capturing the interplay between data reporting, policy intervention and public reaction. A deeper enquiry into the underlying geographical, structural and cultural factors will no doubt follow, as it did after 1918-19.

Should the response to COVID-19 have been more (or less) local? Should ‘moles’ have been ‘whacked’ for far longer at the district level, as in 1918-19? How did different communities feel as policy and authority shifted to and between the centre and the provinces? Which urban centres found their voices heard, and which places were left forgotten? How did the views in Hull compare to those in Leicester, Oldham, Gateshead or indeed Brighton?

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.