Further closures of schools, while necessary to contain the spread of COVID-19, are likely to exacerbate educational inequalities. Learning losses could have long-term consequences for the life chances of children from disadvantaged backgrounds, explain Andrew Eyles and Lee Elliot Major (LSE).

Closing schools is one of the most difficult decisions that governments have had to make in their efforts to halt the spread of COVID-19. This is a trade-off between the costs to health and education. While ministers have been forced into further closures as coronavirus cases peak once again, they should also be aware of unequal and long-term damage that learning losses could have on the nation’s children.

Initial lockdown

When the pandemic first peaked early in 2020, the UK became one of 45 countries in Europe and Central Asia to close its schools. By 20 March, only vulnerable children and the children of key workers received classroom-based instruction. For most pupils, school closures lasted for around 12 weeks.

The resultant learning losses have been disproportionately felt by poorer pupils. The home learning divide was due to variations in several factors, including: the effectiveness of school delivery of online teaching; the capacity of parents to home school their children; the availability of quiet study space and internet connectivity; and the ability to pay for private tutoring. Initial analyses of parental and child time use during lockdown highlighted a stark socio-economic divide in lost learning hours.

Our own analysis into COVID-19’s impact on education and economic inequalities was conducted with national household panel data from Understanding Society and our own bespoke survey. We find that nearly three-quarters of private school pupils benefitted from full school days during lockdown, nearly double the proportion of state school pupils (39%). Meanwhile parents in the highest fifth of incomes were over four times as likely to supplement their children’s learning with private tuition than parents in the lowest fifth of incomes (15.7% compared with 3.8%).

Parents are well aware of the differences in their ability to plug the gap caused by school closures. When we asked parents of school age children the extent to which they felt they had been able to make up for learning losses during the first lockdown, we find a strong divide by parental income (Figure 1). Of respondents in the top fifth of earners, 86% reported being able either to make up a little or a lot of the lost teaching hours. In contrast, only 29% of those in the bottom fifth of earners expressed the same beliefs.

Figure 1: Parents’ views of their ability to make up for learning losses during the first lockdown

Note: LSE-CEP Social Mobility Survey, September/October 2020 Parents of those in full time education, sample size = 1962

Persistent divides

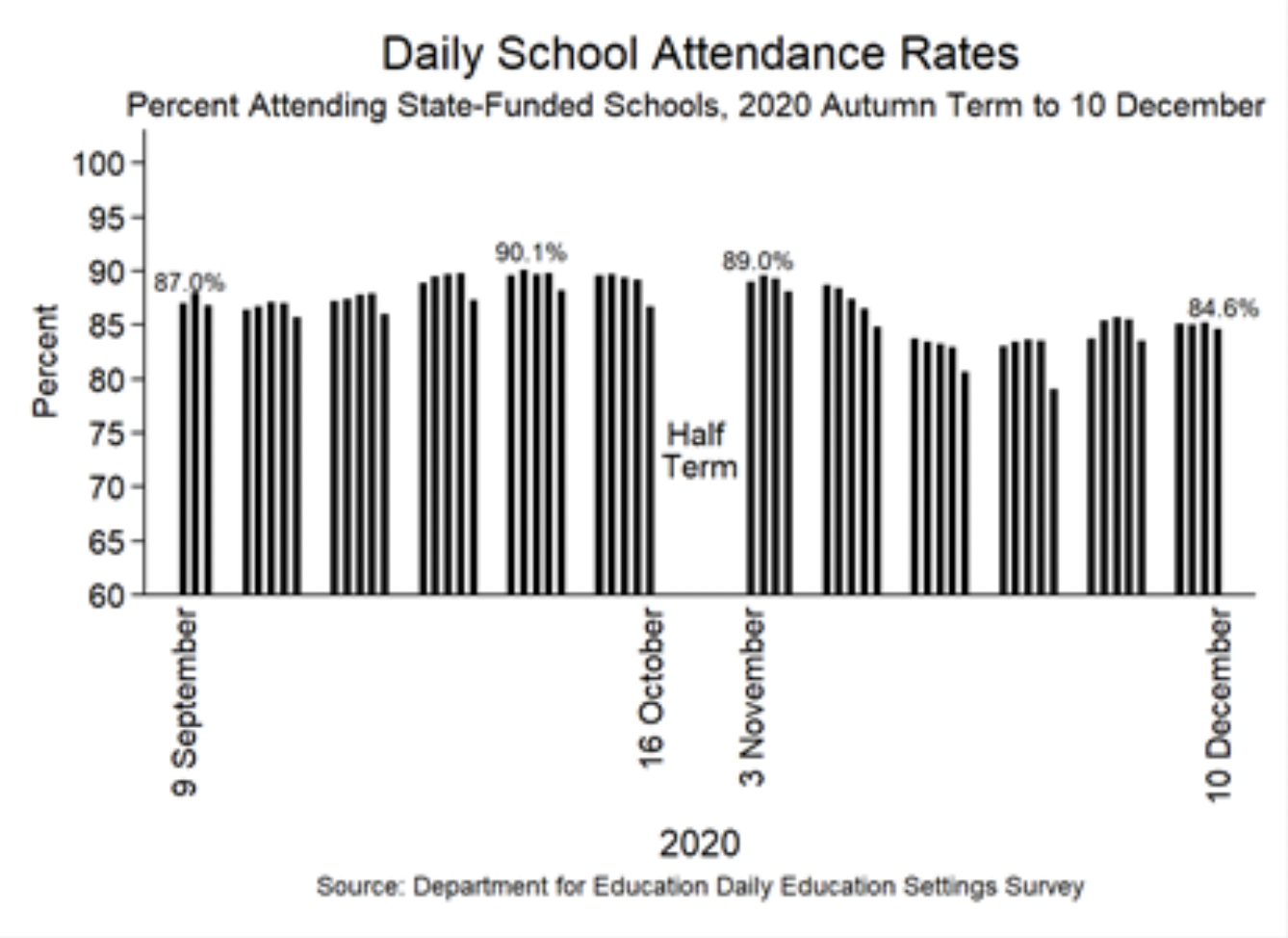

The majority of the nation’s schools opened their gates in September 2020. Despite the re-opening, school absences due to COVID-19 meant that learning still did not return to pre-lockdown levels. Data from the Department for Education show that average attendance at state schools in England hovered between 85% and 90% over the course of the autumn term before falling to 84.6% in the week prior to schools breaking up for Christmas (see Figure 2). Secondary schools saw lower attendance than primary schools, and attendance was particularly low in London and South East England.

In a similar fashion to learning losses during lockdown, the aggregate picture obscures considerable heterogeneity in the experiences of pupils from different backgrounds.

Figure 2: Department for Education statistics on attendance at English state schools

Figure 3: Statistical relationship between additional school absences and disadvantage

This is shown by looking at the statistical relationship between the average number of missed days over the course of the term and the proportion of pupils on free school meals (FSM), a standard measure of disadvantage (see Figure 3). Children in more disadvantaged areas have suffered from more school absences. At local authority level, each 10-percentage point increase in the proportion of pupils eligible for FSM is associated with an extra 1.4 to 1.8 days missed per pupil over the course of the autumn term. Authorities with the lowest proportions of FSM pupils experienced two missed days per pupil during the autumn, while authorities with the highest proportions of FSM pupils experienced 9.6 missed days.

Educational scarring

Emerging evidence shows that school closures have widened achievement gaps between poorer pupils and their more privileged peers. One study finds significant falls in test scores for a large sample of 11-year olds in Flemish schools in Belgium who returned to take tests in June 2020. Research suggests that pupils could experience a range of learning losses of between three and six months during the academic year, with disadvantaged pupils most likely to be falling behind. Even small falls in test scores can damage life chances if pupils fail to cross arbitrary grade thresholds needed to pursue further education.

Economists have shown that early investments in children’s skills raise the efficacy of future investments. Skills beget skills. The converse holds for skill deficits. Young children who have missed out on key parts of the curriculum are less likely to benefit from their lessons once they return to school. This is likely to have a detrimental effect on future levels of social mobility, particularly as the pandemic has worsened economic and educational inequalities at the same time. Parental job loss not only has large effects on educational attainment, it also has large intergenerational effects. One study shows that parental job loss during childhood is associated with lower earnings in adulthood, particularly for poorer families.

Implications for further school closures: what can be done?

The evidence of learning losses suffered during the pandemic so far suggests that the further school closures announced in January 2021 are likely to exacerbate educational inequalities. This may be why there was so much public support for keeping schools open. Of the parents who responded to our September questionnaire, 71% said that the long-term risks of not going back to school in the autumn term outweighed the benefits of limiting the spread of COVID-19.

The priority for social mobility was to avoid school closures for as long as possible, a position that nevertheless became unsustainable with the increasing spread of the new variant of the virus. With schools now closed across the UK for another extended period, the short-term priority should be to ensure high-quality online learning accessible to all pupils.

The Prime Minister’s announcement that ‘it’s not possible or fair’ for all exams to go ahead this summer in England leaves a huge education dilemma: how to create a fair way of allocating life-defining grades for over a million teenagers. We already knew that pupils in Wales and Scotland will not be sitting exams but will be assessed by their teachers. One review suggests that retaining exams with some important adjustments is still the best and fairest way to assess pupils. The exam regulator, Ofqual, has been charged with coming up with the ‘alternative arrangements’ in England. The suggestion is that this could be some combination of exams and teacher assessments.

The challenge with any assessment system is catering for differential learning loss. One option would be to create a one-off special flagging system alongside exam grades to identify pupils who have been most seriously affected by COVID-19. Universities, colleges and employers would take their extenuating circumstances into account when judging the grades. In addition, sustained learning losses may justify further reforms that go beyond simply changing exam protocols. With school closures likely to be extended to mid-February 2021, many pupils will have missed half of their classroom-based learning since March 2020 (a normal school year is composed of 39 weeks). A radical option in this direction would be to allow greater flexibility for pupils to repeat a whole school year.

Unless action is taken, reduced hours of learning, persistent absences from school and weakening economic conditions at home equate to bleak prospects for the young. Before the pandemic, they were already facing declining absolute social mobility. The legacy of the pandemic could be a long-term decline in relative social mobility – driven by the scarring effects of earning and learning losses.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It was first published on the Economics Observatory’s blog. The authors’ research with Stephen Machin is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) as part of the UK Research and Innovation’s rapid response to COVID-19. The authors gratefully acknowledge this funding under grant number ES/V010433/1.

1 Comments