Fast-changing events mean policies quickly become obsolete. But there are often high exit costs – and these are not just financial. Jintao Zhu (LSE) recommends how governments can incorporate exit costs into policymaking.

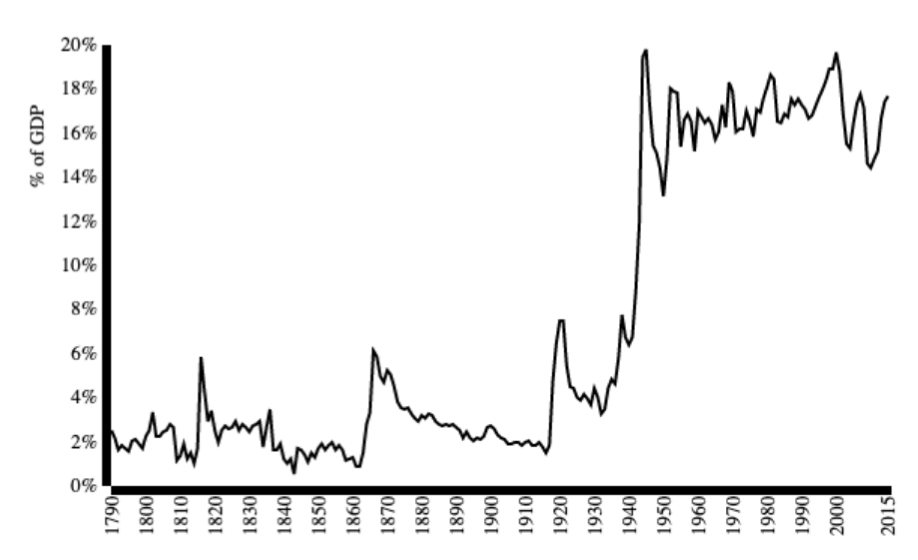

In 1940, the US government collected $7 billion in tax revenue. By 1945, the figure had soared to $45 billion. The drastic increase is not surprising, as the second world war brought the urgent need for much larger national spending. What is surprising is that the tax spike never came back down after the war ceased. As Figure 1 shows, the US never abandoned its wartime tax policy.

Figure 1: US government revenue, 1790-2015

(Galka, 2016)

We live in an uncertain and unpredictable era, confronted by crises that require swift responses. Decisions need to be made before events fully develop. We do not have the luxury of full information or sufficient evidence. For example, governments had to decide whether they should close borders or ban public gatherings before the true infection rate and health risks of COVID-19 were fully known. These rushed policies may fail to address the challenge, or even exacerbate the crisis. And because of the speed of change, existing policies soon become obsolete or insufficient to protect individual welfare and social justice. For instance, personal data usage and privacy have become a much bigger concern in the digital age. The prevalence of working from home during the pandemic brings new challenges to work-life balance and work ethics. Policies today have a shorter lifespan because they may no longer be useful when circumstances change. (Of course, there are many long-term policies, but they complement rather than substitute for short-term policies.) This means we need to incorporate exit costs into policymaking.

I define exit cost as the cost of abolishing an established policy. If the exit cost is high, policymakers will suffer from severe pain when they need to abandon the policy. In the worse scenario, the cost is so high that policymakers have to keep the policy and bear the long-term detrimental effects of an outdated scheme.

Exit cost has three components. Firstly, there is the direct expenditure of revoking the policy, which usually involves financial and human resources. For example, when China abandoned its one-child policy, it needed to amend relevant regulations, inform related organisations and educate the public about the benefits of having multiple children.

There is also an indirect cost. When the policy is popular, there is resistance to changing it. In his study of the resource curse, Terry Lynn Karl argues it is almost impossible for the oil-rich Middle East governments to stop giving transfers when the oil price collapses. The halt of the popular generous transfer policy can lead to massive repressions and protests, creating political and social instability. Such a heavy political exit cost is almost unaffordable for the government.

Lastly, there is the “legacy cost” – the lasting influence of an abolished policy. Some of these legacy costs are relatively obvious. A disastrous policy will damage citizens’ trust towards the government even if the policy is revoked early. It becomes more difficult to persuade parents to give birth to more children after they have become deeply convinced of the benefits of having only one child. Policies can even alter certain social norms or cultural values. Michael Sandel argues that pecuniary incentives crowd out moral motives in the long run. If governments pay people to cut emissions, they will exclusively link emission cutting with monetary rewards. After the government stops providing monetary rewards, people will not only stop cutting emissions but also lose the guilt and sense of social responsibility which had encouraged people to make some (sub-optimal) efforts to cut emissions before the financial incentive was introduced.

How can we incorporate exit costs into policymaking?

1. Make exit cost “a variable in the function”

When we evaluate a potential policy, as well as establishing the conventional costs and benefits, we should leave space for exit costs. Policymakers should do their best to estimate the possibility and damage of exiting the policy. The calculated value should be added to the cost side of the equation, before comparing it with the potential benefits.

2. Always have an exit plan

Policymakers should understand the conditions that justify the implementation of a particular policy. They should research the circumstances in which the policy becomes obsolete, how to exit the policy smoothly, as well as the potential alternative plans. For instance, when should a country end a full-scale lockdown? How can the lockdown be lifted smoothly, so that people do not start gathering in large numbers and push up the infection rate again? What are the replacement policies for the lockdown? Answers to these questions ensure well-prepared and responsive policy transitions when the circumstance changes.

3. Minimise exit costs where possible

Policymakers should consider using materials or methodologies that are unlikely to incur a huge exit cost and use structures that can be dismantled when tackling temporary projects. The London Olympics dismantled 55,000 temporary seats after the event as part of the post-Games regeneration plan. Policies such as grants or tax cuts that are “addictive” should have pre-established ‘expiry dates’. Strong institutions should ensure policies are ended in a legal and justified way, so as to reduce mass resistance to policy withdrawal.

4. Be sceptical about implementing policies with a high exit cost

Policymakers should think twice about imposing policies that could incur a severe exit cost. For example, they should avoid policies that promise citizens long-term transfers without an expiry date, or that play on patriotic fervour that could degenerate into radical populism. For policies that have a high exit cost but must be implemented, policymakers should be far-sighted and ensure the policy does not rapidly become outdated. For example, new and expensive public infrastructure should be compatible with current and likely future environmental demands.

Governments must contemplate the exit cost before implementing a new policy, especially in this uncertain and dynamic world. We need adaptable government that is ready to adjust its policies responsibly.

Offline reference

Sandel, M. (2013). What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments