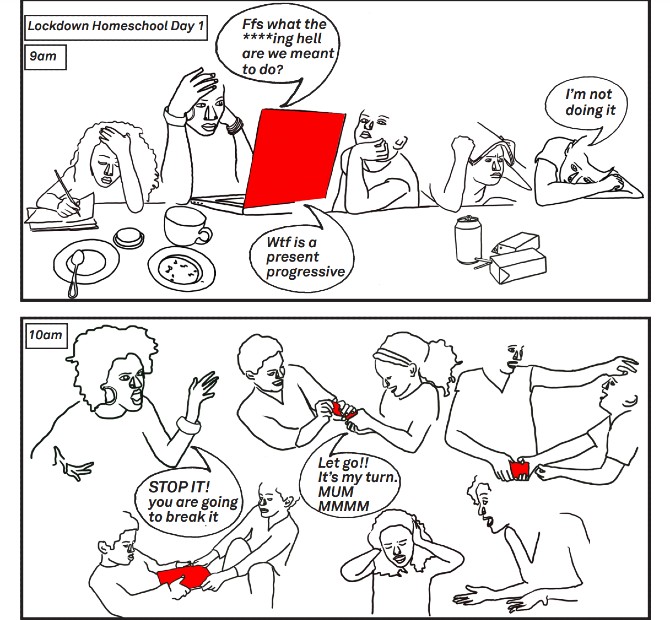

The working-class experience of lockdown has been routinely sidelined. Lisa Mckenzie (Durham University) collected 38 lockdown diaries describing the isolation, fear and loneliness of this period, which will be illustrated and published in a cartoon-strip format to make them accessible to everyone.

The pandemic has challenged the university system. That is an understatement. Our courses are mostly taught remotely. Lecturers, support staff and the whole university system have showed incredible resilience and commitment in how they have tried to make the learning and teaching experience work well under unprecedented and often impossible conditions. Personally, I have found this very challenging: headaches, fatigue, lost emails, over-stressed and frightened students – but on reflection, there has been something very special and profound about teaching sociology through such an insecure and frightening period. I can honestly say my students, despite the obvious challenges, have thrived in thinking sociologically. The university and the discipline have left the building and interloped into their lives and their homes, and the results have been, in my experience, a far deeper and connected experience of the discipline.

As an active researcher who brings together my teaching and my research practice – I see them both as integral parts of what a university should be, and its responsibility to a good society relies on that symbiosis – I can see that the research process has been put under great strain. While the country and most of the world have been in lockdowns, and health services at breaking point, while publics and societies have been grieving for lives lost, changed and ended, the need for those of us who research communities, inequality, and social, cultural and economic mobilisation has never been so important. Yet the pandemic has meant that methodologies to find out the impact, especially on the poorest and marginalised communities, have almost been halted.

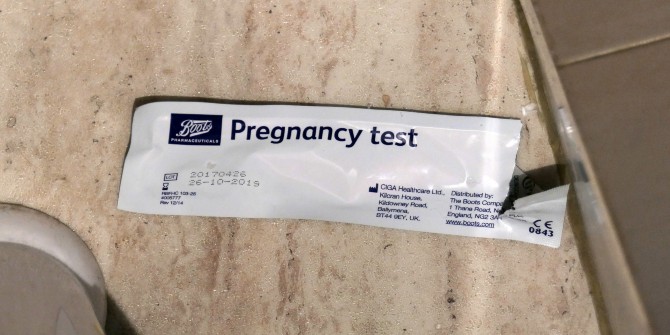

I learned – as did all of us who worked on the Great British Class Survey project at the LSE back in 2013, led by Mike Savage – that people who live and survive at the bottom of society with the fewest resources are the most difficult for wealthy and institutionally middle-class places and people, like academics and university research centres, to reach. When the Great British Class Study was launched, less than 1% of the bottom category in the schema self-selected to take part in the research. My job was to go out and find the missing proletariat and the working class. This is what I do – I’m an ethnographer and go into communities. I spend time there, I gain trust, I engage working-class people with the research process rather than research them. My research diaries are full of maps, doodles, pictures and poems written by respondents. Over the years I have been sent videos, photos, short stories, and newspaper articles by respondents engaged in the various pieces of research I have been involved in – artefacts of working class life.

So in March 2020, as lockdowns began, I had one eye on how these strange times would be understood, unravelled, and told in the near and far future. I thought about whose voices would come through, which experiences would be listened to, and consequently who would be the winners and who would be the losers, as there always are when social, cultural and economic tectonic plates start to shift. As a working-class academic, woman and ethnographer, I knew whose voices and stories would have power and agency, and whose stories would be narrated about them – by politicians, media bubbles, and of course academic researchers.

I drew on my experience of working in marginalised communities and my academic training and practice as an ethnographer to think through the ethical, and practical challenges of ensuring that working-class people’s stories and experiences would be told by them, not about them. I asked working-class people who I had worked with on other projects, and recruited others over social media to take part in a short project to document their everyday lives in the first few weeks of lockdown in the UK. Of course, I had my own concerns about the welfare of my participants. My research always has and always will have the welfare of marginalised communities and people front and centre. I am well practiced in asking myself whether I am the right person to do this research. I also know that I have no right to ask marginalised communities for anything they may not want to give – and absolutely no right to ‘speak about’ them. These questions led me to devise a research methodology fusing together ethnography and diary writing.

I recruited 38 individual working-class diary writers. Some of them wrote for four weeks, while mothers who were home-schooling did 5-7 days. I was sent pictures, images, traditional diaries, doodles, and short video diaries. They add up to an enormous amount of rich data from those first weeks of lockdown. I was totally unprepared for the level and depth of emotion contained in this material, but also the emotion they would provoke in me. I was not a distant observer. I was facing many of the same challenges as my diary writers: isolation, fear, and loneliness.

It has taken me almost a year to analyse the data. My fear was that the academic process of dissemination would, as it always does, diminish the living, breathing quality of these experiences. Both Pierre Bourdieu and Paolo Freire have challenged the ways in which the academic process silences, closes down and cleans up the stories of the working class into acceptable chunks of academic data packages that rarely challenge the status quo. Consequently, the power of those lived experiences are dulled and spoken through the mouths of the middle-class research process, meaning truth is never spoken to power.

Bourdieu argues in An Outline of Theory and Practice that our research practice must be flexible and reflexive: the ideological tools researchers and academics use should not be imposed on our subjects to such an extent that methodology and ideology alienate them from their own testimony. He sees this rendering of ‘rules and models’ as an act of bad faith by the sociologist. Paolo Freire’s manifesto, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, is an important book for any educator or researcher who aims to use their research or teaching for political change, and to argue that marginalised people’s experiences should never be forced or integrated into oppressive structures, but instead those structures must be changed to allow those voices to have room to be heard.

I want ‘Soraya’ to be in five dimensions as she recounts those first days of home-schooling with two smartphones and a laptop as a 36-year-old mum of four, living on a council estate in Nottingham. Her own education was substandard and she left school with no qualifications. I want to show her frustration at not understanding the briefs sent by the teachers, how she felt inadequate and scared as she did when she was at school – which left her and her children all sat under the kitchen table, crying and holding each other as they all felt the weight of failure.

Or ‘Anna’, who watched her elderly neighbour die of COVID from her window, knowing the supermarket delivery he had awaited for two weeks came the day before he died, worrying about the food going off in the fridge and thinking what a shame he never got to eat it after waiting so long.

I am taking a risk. These voices which came to me over the internet when we were all locked in our homes will initially be published and disseminated in a way that has been part of many truly radical movements, from Black Power to the early international labour and solidarity movements – the graphic novel, art and cartoon strips. It is a working-class art form which is accessible to everyone, regardless of their formal education. The humour, resilience, resistance, pain and the unfair experiences, judgments and structural inequalities that working-class communities live with daily and through every generation will not be washed away in academic prose, or through the partisan snobbery of the peer review sieving process. This research will be published on DIY principles and in working-class solidarity. The team working with me are all working-class creatives and artists with a commitment that our voices will not be spoken over. The project will produce a beautiful hardback book published by Itchy Monkey Press, and the project will hopefully continue to devise and create other working-class methodologies, fusing our skills with those of the academy. I hope we will all be welcomed.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments