Several COVID-19 vaccines are now licensed, and the success of a rollout often depends on people’s willingness to accept any of them. Health workers are in a unique position to influence the public. Jan Priebe (German Institute for Global and Area Studies), Henning Silber, Christoph Beuthner, Steffen Pötzschke, Bernd Weiß, and Jessica Daikeler (GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences) show how their recommendations change when they are given different types of information about vaccines.

The success of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns depends on the fast and widespread uptake of the vaccines among the general public. With different types of vaccines now readily available in almost all European countries, the policy focus is shifting toward demand-side constraints. Vaccine hesitancy is a particular issue. To increase vaccination rates, governments rely on information campaigns that deploy various individuals (health experts, celebrities, religious leaders), channels (media, health centres, religious institutions), and topics (the risks of the virus and the safety of the vaccines).

Whether these campaigns are effective will depend on issues of access and trust. For instance, while some people might not be reached through conventional media outreach campaigns, others might distrust the government and therefore disregard them. In this context, health workers such as nurses, paramedics, doctors, and health administrators are important actors. They have direct access to patients, relevant experience, and are often considered highly trustworthy. In this way they are in a position to provide informal advice that can influence their patients, friends, family and the wider public.

Yet little is known about the type of vaccine recommendations that health workers give. Informal advice might differ from public recommendations, for a number of reasons. First, health workers are a highly selective population that (i) has an intrinsic interest in health topics, (ii) received more extensive training on the benefits and risks of vaccines, and (iii) is at high risk of catching COVID due to their work on the frontline. Second, health workers – like anyone else – are exposed to multiple sources of information when forming their own opinions. As such, they can be affected by misinformation, selective information processing, and the public debate in general.

To better understand health workers’ attitudes toward different types of COVID vaccines and how their views are affected by the public debate on the merits and risks of a particular vaccine, we carried out an information treatment experiment within a German online survey conducted between April and May 2021. Participants were recruited using advertisements on the social network sites Facebook and Instagram. We asked 2,359 health workers to rate whether they would recommend any of six COVID vaccines (Pfizer/BioNTech, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, AstraZeneca, Sinopharm, and Sputnik V). Answers could be provided on a seven-point response scale from “unlikely” to “very likely”.

The information treatment consisted of a control group and four different treatment groups. Health workers were randomised into one of the following five groups:

Group 1: Misinformation and conspiracy theories. Subjects received information which highlighted arguments typically used by advocates of conspiracy theories. Examples included: COVID vaccinations can cause cancer; COVID vaccines were not sufficiently tested.

Group 2: Scientific AstraZeneca (AZ) debate. Subjects were exposed to the arguments and debate that led to German regulators halting vaccinations with AstraZeneca, with the European Medicine Agency (EMA) later reiterating the safety of the vaccine.

Group 3: Own health. Subjects received scientific information about the possible negative consequences of a COVID infection. It was highlighted that vaccinations could reduce the likelihood that the subject suffered severe disease.

Group 4: Public health. Subjects were informed about the rapid spread of COVID in Germany. The aggressive transmission and the possible severe consequences for other people’s health were highlighted.

Group 5: Control group. Subjects received no additional information before being asked about their vaccine recommendations.

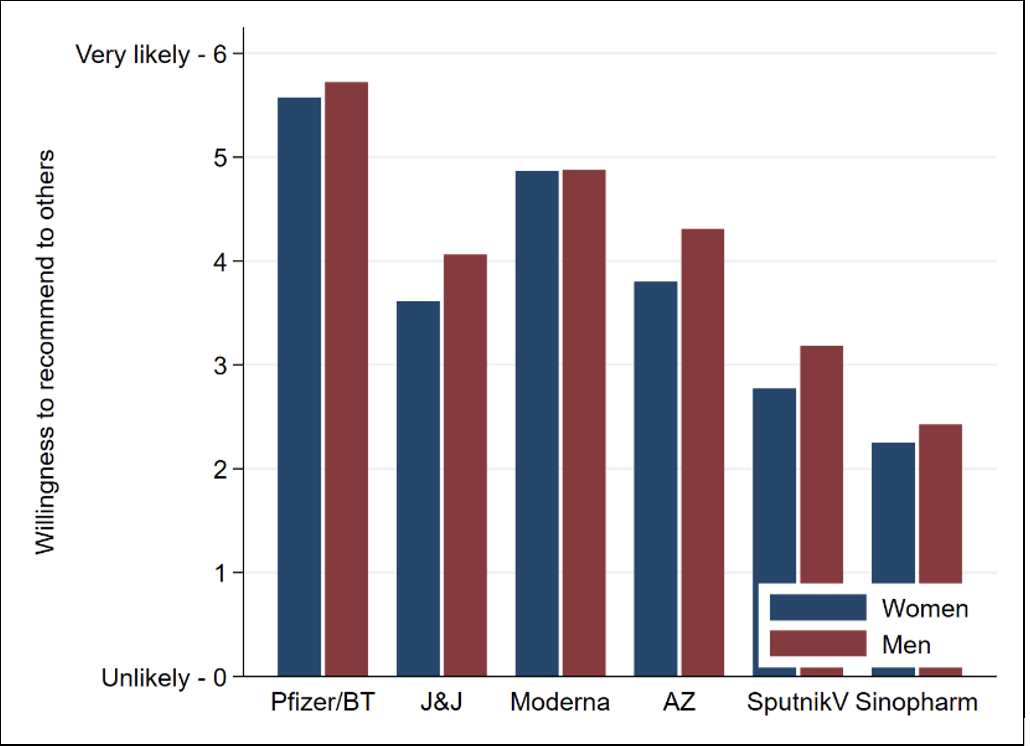

Figure 1 shows the likelihood that health workers in the control group (i.e., in the absence of our information treatments) would recommend any of the six vaccines. Among both men and women, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine was strongly recommended by almost all health workers, and the likelihood of recommending Moderna was also high. The willingness to recommend Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca was at a medium level. Finally, Sputnik V and Sinopharm were least likely to be recommended. Men were slightly more likely to recommend five out of six vaccines. This effect was particularly visible for AstraZeneca, possibly due to the ongoing public debate in Germany that emphasises rare side effects of the vaccine among young women.

Figure 1. Willingness to recommend vaccines to others (control group only)

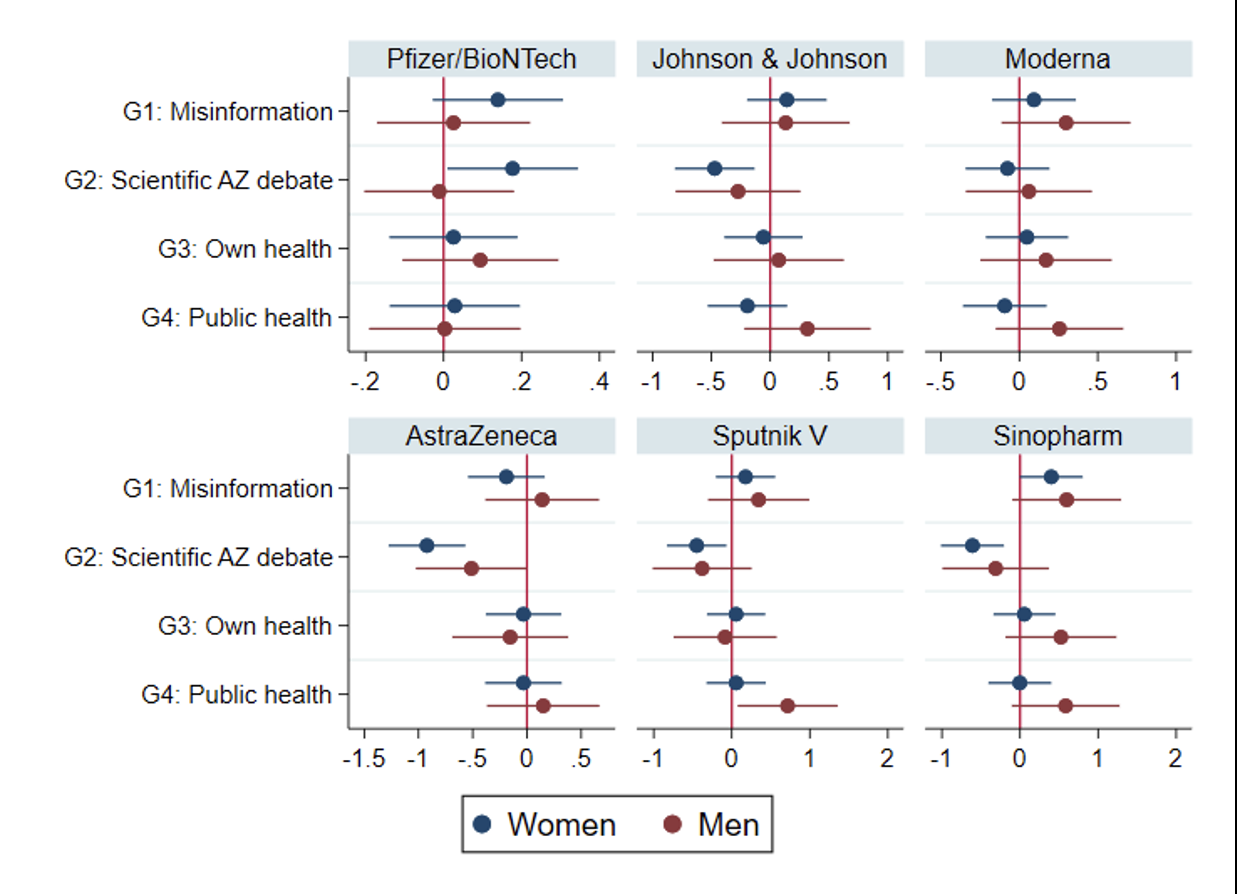

We next investigated how the different types of information given would affect the participants’ recommendations (see Figure 2). Health workers proved to be highly responsive to the AstraZeneca information treatment (Group 2). Both men and women became substantially less willing to recommend AstraZeneca to others. Second, there were strong gender-specific spill-over effects in the AstraZeneca information treatment group. Providing female health workers with objective information on the AstraZeneca debate did not only make it less likely they would recommend it, but affected the other vaccines that were less established in Germany at the time of the survey (Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, Sputnik V, Sinopharm). Moreover, female health workers developed a stronger preference for the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. Among male health workers, we did not observe any type of spillover effects on other vaccines. Importantly, health workers did not react to any of the other information treatments.

While these findings suggest that health workers are resistant to conspiracy theories, they highlight the limits of vaccination campaigns that appeal to people’s concern for their own and other people’s health.

Figure 2. Impact of information treatments on the willingness to recommend vaccines to others

Note: The figure shows how the different information treatments affected the vaccine recommendations of health workers. The effect of each of the treatments is compared to the control group. The bars show 95% confidence intervals (CI). If the dot and the CI are left of the vertical red line, the treatment had a negative effect on the vaccine recommendations, and if the dot and the CI are right of the line, the treatment had a positive effect on a vaccine recommendation.

The results of our study indicate that health workers are largely unaffected by misinformation and conspiracy theories. Nonetheless, the debate surrounding the AstraZeneca vaccine seems to affect their vaccine recommendations considerably. The scientific and policy discourse on AstraZeneca did not only reduce people’s willingness to get its vaccines, but might have spillover effects on other, less established vaccines such as those manufactured by Johnson & Johnson and Moderna. Given that the fast and efficient rollout of the campaign depends on people accepting different types of vaccine, the AstraZeneca controversy might have limited the government’s options. Clearly, if people are less open to other vaccines, it will slow down the vaccination campaign.

The results are part of a research project that investigates the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the life and work of health workers in Germany.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments