Global welfare has taken a turn for the worse in the age of COVID, with both health and income levels under threat. Francisco Ferreira (LSE), Olivier Sterck (University of Oxford), Daniel Gerszon Mahler, and Benoit Decerf (World Bank) estimate the worldwide mortality and poverty generated by the pandemic and compare these two sources of welfare losses by expressing them in a common metric: years of human life. For most poor and middle-income countries, greater economic deprivation has been a more important source of loss in well-being than premature death.

Since its outbreak at the end of 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought massive losses in well-being all over the world, mainly through its health and economic consequences. But which of these two types of consequences constitutes the largest welfare loss? Does the answer to this question vary systematically across countries? How large were the aggregate welfare losses, and how were they distributed across countries? Clearly, we cannot come close to bringing definite answers to these questions given that the pandemic is still ongoing and given that the available data is still scarce. However, in a recent paper, we begin to probe these questions.

We focus on the immediate and most extreme outcomes along the health and income dimensions: death and destitution. We estimate the worldwide mortality and poverty generated by the pandemic up to December 2020 and compare these two sources of welfare losses by expressing them in a common metric: years of human life.

Mortality is measured by the number of years of life lost due to COVID-induced deaths. Destitution is measured by the number of additional years spent in poverty due to the pandemic. The “lost years” can be compared to the “poverty-years” using a single normative parameter: how many poverty-years generate the same welfare loss as one lost year. Concretely, one can think of this parameter as some aggregation of the answers people might give to the following hypothetical question: “If you could make this bargain, how many years would you be willing to spend in poverty during the rest of your life in order to add one additional year at the end of your life?”

We compute our estimates for a given country as follows. For the number of lost years, we rely on the number of COVID-induced deaths officially reported in the country. We infer the age distribution of these deaths, and, for each death, the number of lost years is taken to be the country’s remaining life-expectancy at the age of death. We get our estimates of the number of lost years by summing over all COVID-induced deaths. For the number of additional poverty-years, we rely on the country’s income distribution before the pandemic and on the shock to 2020’s gross domestic product (GDP) that could be attributed to the pandemic. We assign (part of) the GDP shock to individual incomes in order to assess how many additional individuals could have their 2020 incomes fall below the poverty line because of this shock. Focusing on the immediate consequences, we assume that these individuals stay poor only for one year: 2020. Hence, the number of poverty-years corresponds to the estimated number of additional poor. Our estimates are crude, but hopefully provide a sensible order of magnitude.

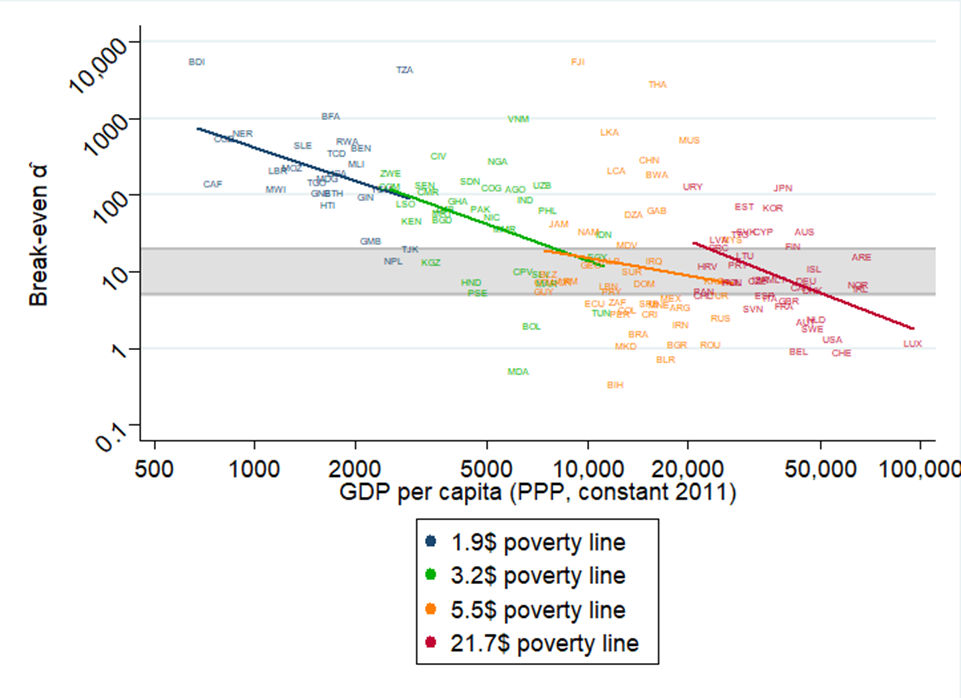

Our first finding is that the mortality burden of the pandemic, relative to the poverty burden, is much higher for higher income countries. The mortality burden increases sharply with GDP per capita. One key factor explaining this gradient is that COVID mortality increases markedly with age, and richer countries have much older population pyramids. The poverty burden, on the contrary, declines with per capita national incomes when a constant absolute poverty line is used (i.e., the $1.90 a day international poverty line), or is uncorrelated with national incomes when a more relative approach is taken to poverty lines. Even when taking a relative definition for poverty, we estimate that for each lost year there have been between 100 and 1000 poverty-years in most low-income countries, whereas there have only been between 1 and 10 poverty-years in many high-income countries, as illustrated in Figure 1. If one believes that a lost year brings the same welfare loss as five poverty-years, poverty was by far the major source of welfare losses in 2020 in many low-income countries.

Figure 1. Break-even alpha (=ratio of estimated number of poverty-years per lost-year) as a function of GDP

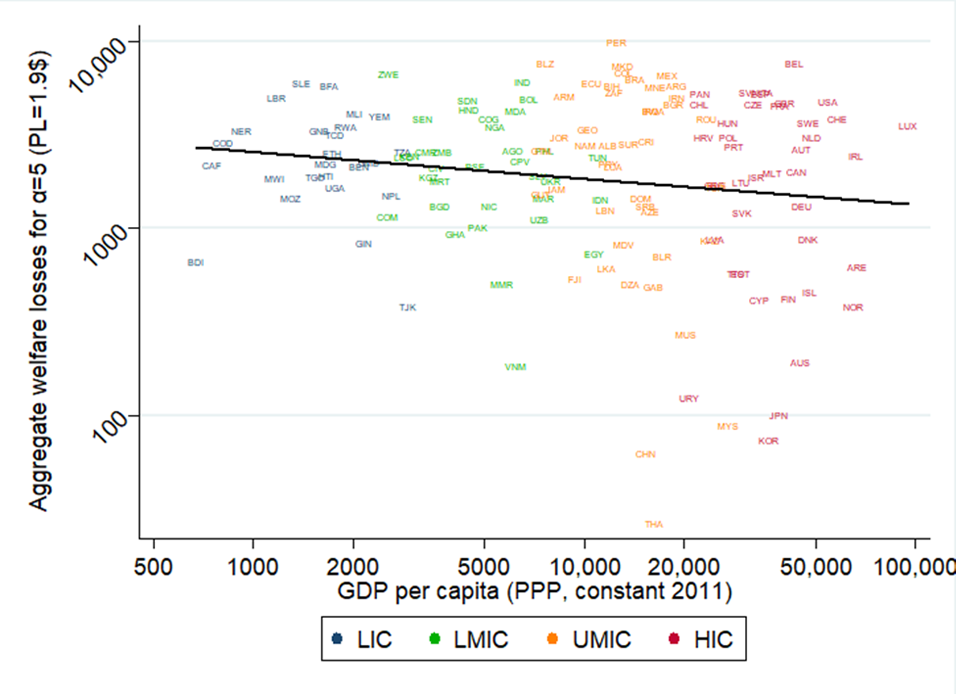

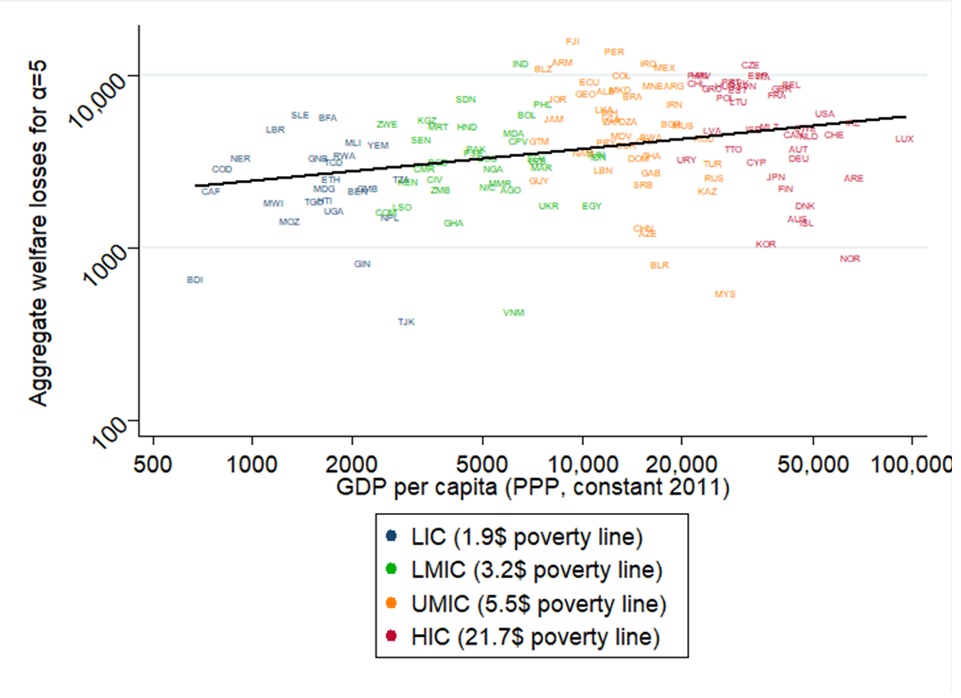

The second finding is that the distribution of aggregate welfare losses – combining mortality and poverty losses expressed in terms of life-years – depends both on the choice of poverty line(s) and on the relative weights placed on mortality and poverty. With a constant absolute poverty line and a relatively low welfare weight on mortality, poorer countries are found to bear a greater welfare loss from the pandemic. When poverty lines are set differently for poor, middle and high-income countries and/or a greater welfare weight is placed on mortality, upper-middle and rich countries suffer the most. Figure 2 illustrates this by contrasting the two definitions of poverty, when assuming that a lost-year brings the same welfare loss as five poverty-years.

Figure 2. Aggregated welfare losses expressed in number of additional poverty-years per 100,000 people (1 lost-year is assumed as bad as 5 poverty-years) as a function of GDP.

Clearly, there is substantial variation in the estimated consequences at any level of GDP. In particular, the relatively small mortality consequences registered by some rich societies with very old populations, like Japan and the Republic of Korea, reveal that public policy responses do make a difference: demography is not destiny.

There are obviously many limitations to our analysis. Our estimates are crude and based on partial and imperfect data. We consider only the pandemic’s immediate mortality and poverty consequences ignoring, for example the likely important and long-lasting negative consequences of the large changes in the provision of schooling during the last year. Perhaps most importantly, the pandemic is still ongoing and the unequal access to vaccines between countries looks set to reduce both the mortality and poverty burdens much more markedly in rich than in poor countries during 2021.

Despite these important limitations, our analysis does suggest that the poverty consequences of the pandemic should be given as much importance in the global policy conversation as its mortality consequences. For most poor and middle-income countries, greater economic deprivation has been a more important source of loss in well-being than premature mortality. Ignoring the large welfare costs of destitution would lead us to the wrong conclusions about the distribution of the burden of the pandemic across countries, exaggerating the share of suffering visited on richer countries to the detriment of poorer ones.

This post first appeared at the World Bank blog, and is based on Death and Destitution: The Global Distribution of Welfare Losses from the COVID-19 Pandemic, LSE Public Policy Review. It represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments