Reviving Britain’s high streets after the pandemic is not just about supporting shops, says Ricky Burdett (LSE). It requires recognising the social value that they provide to the surrounding neighbourhood as places that sustain complex, inner-city living.

There has been talk of the death of the city in the COVID era. This is highly exaggerated. Very few cities have completely collapsed, and many are coming back relatively swiftly. Indeed, early in the pandemic, some commentators thought that particularly dense cities would suffer more because they were conducive to the spreading of the virus. In fact, that has not been the case.

The Asian cities of Hong Kong, Seoul, Singapore and Taipei are some of the densest in the world, but they dealt with the disease better than sprawling cities due to more efficient systems of control and distribution of services. Their previous experience with SARS also made an important difference in how the pandemic was tackled and how the public responded.

Peripheral areas and local neighbourhoods – like Chiswick, Peckham or Camden in London – have shown a degree of local resilience and vibrancy

Singapore stands out as a centrally managed city-state where planning is highly integrated at all levels. Despite the control exercised by Whitehall, England has a far more fragmented political system where some powers are delegated to local authorities. The tensions between central and local government became visible during the pandemic, exposing some of the underlying social and spatial inequalities in urban areas that were hardest hit.

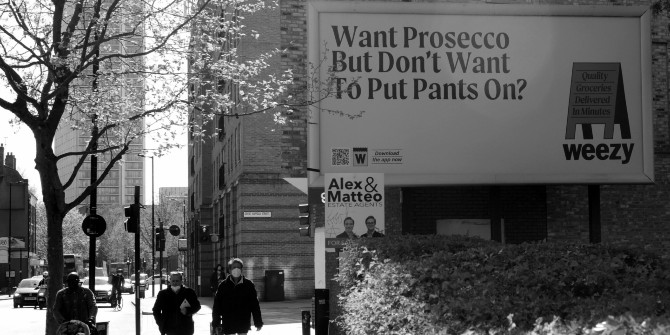

Globally, there have been dramatic changes in behavioural patterns in the ways cities have been affected by COVID. Economic and retail activity in Central Business Districts has been negatively impacted. But peripheral areas and local neighbourhoods – like Chiswick, Peckham or Camden in London – have shown a degree of local resilience and vibrancy. These patterns offer lessons for the way we consider the well-being of the high street. Cities are complex and fragile organisms, with very diverse characteristics between cities and within them. Cities are not uniform entities and any policy response should be appropriately nuanced.

In any discussion about the social and economic well-being of a high street, the physical environment is key. The quality of the public realm dignifies and civilises the urban environment and promotes a degree of civic pride and engagement. Several studies have shown that the high street not only contributes economic value but also social value to surrounding communities.

In this respect, it’s important to consider the wider neighbourhood and not just the high street on its own. The quality of the environment along a high street and in its immediate vicinity contributes to its potential for social cohesion. A landscaped pocket park or well-designed bench can foster community interaction. Giving priority to the ‘urban commons’ has become a popular platform of many city administrations, including Barcelona (with the Barcelona en Comú initiative).

Creating liveable neighbourhoods with high-quality public realm and affordable housing is critical to the economic well-being of the high street. A stable residential population is a perquisite to sustain the local economy. Many European cities are planned around relatively dense local neighbourhoods that support a mix of uses, with an active retail street frontage and workplaces and housing above.

The success of a high street is dependent on mixing uses, activities and people and taking advantage of their urban location and connectivity. The demise of some businesses and retail has been accelerated by online shopping and COVID, leaving some buildings empty or under-occupied. In some respects, this offers an opportunity to adapt buildings to new uses which can make the most of public transport and services nearby. Defunct department stores, for example, are successfully being turned into co-working spaces or leisure venues even though over-prescriptive planning regulations sometimes constrain imaginative solutions.

A landscaped pocket park or well-designed bench can foster community interaction

Urban intensification – bringing more activities closer together – has environmental as well as social and economic benefits. Paris, Milan and Singapore, for example, have invested in planning policies that optimise public transport and walkability, reducing private car dependency. Quality of urban life in inner city areas has improved as noise, congestion and pollution have abated.

COVID has heightened the risks associated with travelling in public transport, and return to normality will take time and adjustment. Nonetheless, the future well-being of the high street or any mixed-use inner city neighbourhood will not be secured – as some have suggested – by providing free parking and reversing the trend towards sustainable mobility.

Britain’s high streets are part of a complex ecosystem that requires multi-level intervention rather than simplistic solutions and knee-jerk reactions. They are an intrinsic part of the social and economic fabric of our cities.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It is based on Ricky Burdett’s contribution to a Housing, Communities and Local Government select committee session on supporting our high streets after COVID-19 on 10 June 2021.