Intuitively, working from home would seem to help reduce carbon emissions. But, as Valentine Quinio (Centre for Cities) explains, people who move out of cities drive more — and those working in poorly insulated homes turn the heating on.

Finding a silver lining to the pandemic is not an easy task. In light of the short-term cuts to global carbon emissions, many have argued that the main benefits were environmental, and that there was a lesson to learn for a post-COVID world: that more remote working would de facto be better for the planet. But is it really the case?

At first glance, the idea makes sense: across the country, including in the largest urban areas, most commutes are made by car. And given that cars account for more than 60 per cent of transport emissions (itself the most polluting sector), more home working would automatically slash carbon emissions.

While the merits of this reasoning are hard to dispute, and it might well be true in some cases, the impact of home working on the environment should not be over-estimated. This is for two reasons.

The first might sound obvious but is worth remembering: not everyone can work from home. Estimates vary between places, from 20 per cent of jobs in Burnley to 40 per cent in Edinburgh. So when discussing the environmental benefits of remote working, the scope narrows down to a relatively small proportion of journeys. And car commuters are less likely to have a job which allows them to work from home than people who use public transport, which further limits the carbon savings potential.

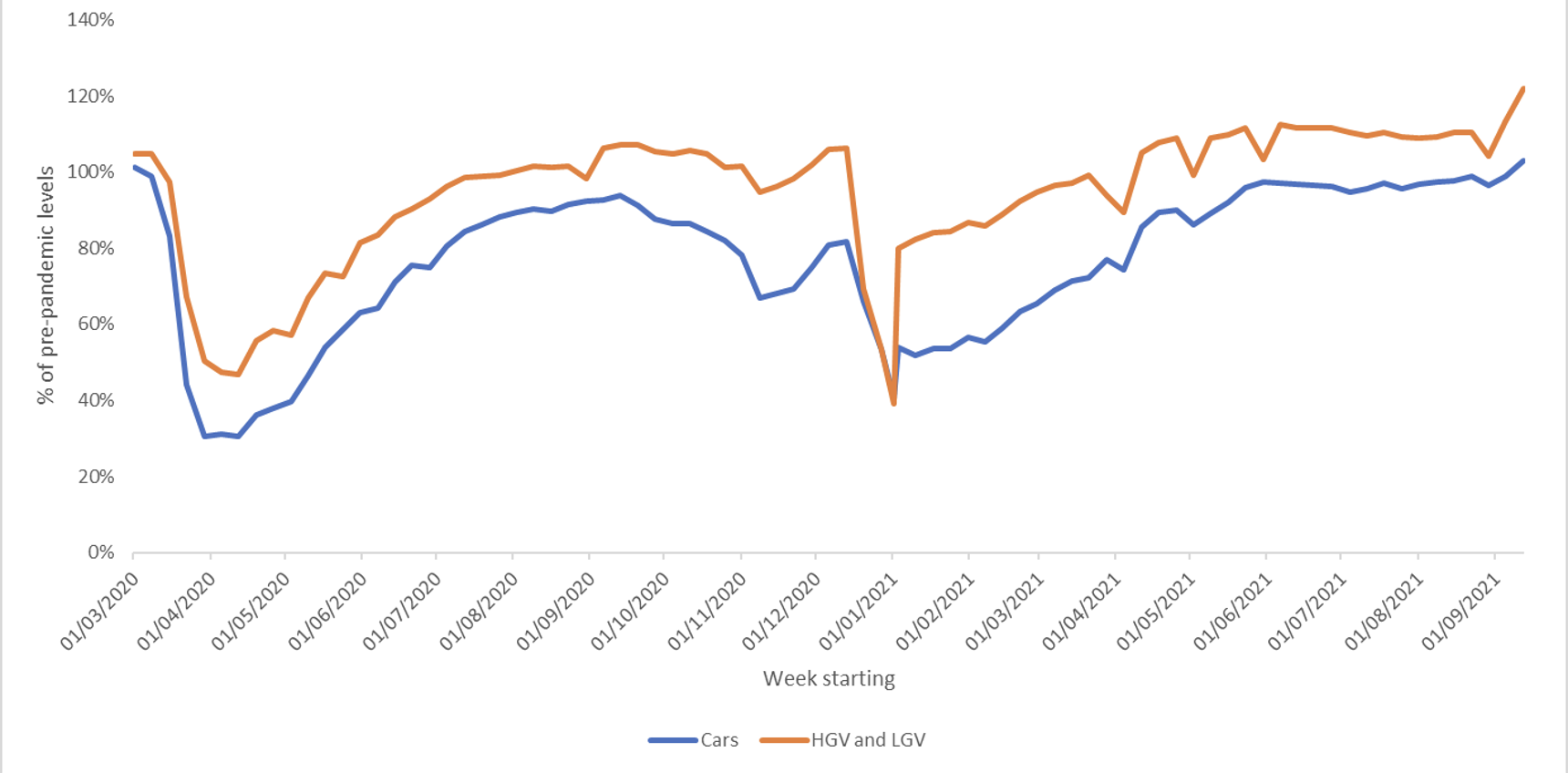

The second, related to the above, is that commutes represent less than 20 per cent of all trips and distance travelled by car, so they are not the largest contributor to carbon emissions. Shopping and leisure trips, on the other hand, account for more than 45 per cent of car trips, and these would not be removed from the equation even if more people worked from their living rooms. (Or if they were, they would be replaced by more delivery vans, with an equal (if not worse) impact on carbon footprints.) This likely explains why since March 2021, traffic levels (from both private cars and other vehicles) bounced back above their pre-pandemic levels despite the fact that many people were still working from home (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Motor vehicle usage 2020-2021

Source: DfT, 2021.

The question gets even more complex when the possible implications of more remote working are considered — for instance, in a scenario where a household moves further away from a city centre to a less dense area because they do not need to commute to the office every day. This has been the dominant narrative in the press since the pandemic started (although there is little evidence of the scale to which it has happened). In this scenario, provided the household used their car for their commute, then they might indeed save carbon on that journey. But they might end up using their car more for their leisure trips if the area they moved into offers fewer alternatives to driving, often a characteristic of low-density environments (either because distances are too long to be walked or cycled, or because there is no or little public transport). This would partly, if not fully, offset the carbon savings of remote working. And if they moved from an area where they did not need a car for most of their trips (in London, 45 per cent of commutes are made by public transport), then their carbon footprint would likely increase.

On top of this are the implications of remote working on energy usage. Staying at home all day necessarily means more lighting, heating and cooking which all generate carbon emissions. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated that in the UK during lockdowns, the average home electricity consumption rose by more than 15 per cent on weekdays. A number of studies have shown that, particularly in winter, remote working is less sustainable because heating individual homes is less efficient than heating offices. In the scenario where a household moves from a city centre flat to a suburban house, domestic emissions would go up: on average, detached houses emit twice as much carbon as flats.

All in all, the impact of remote working on carbon emissions is not clear cut and depends on several factors — from how far we travel to work, to the type of homes we live in. With that in mind, instead of discussing ways of reducing travel demand on commute journeys, we should broaden and reframe our approach to low-carbon transport. Policy should aim at discouraging car usage and facilitating public transport, for all trips and all purposes, including for commuters for whom working from home is not an option, and the car is too often the default choice.

Moving away from car dependency will be easier said than done in many places up and down the country. Cities, which concentrate nearly 60 per cent of all jobs (and most ‘office’ jobs which can be done from home) are the best equipped to face this transition, because of the benefits brought about by density. They now need to tap into these benefits and play their part.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

Hi

I agree with the notion of non commute travel. But I think there are missing piece for the puzzle. Yes the energy us at home went up but what happened to energy use at the workplace?? Also, heating will be turned on as we approach winter but we can’t ignore the fact that some households will have the heating on regardless if there is someone remote working there or not. So for heating it’s not as straight forward as is seems.

Many people like to discuss random points about reducing CO2 emissions etc etc, but in reality I’ve seen clearer sky and clearer air when most people worked from home during the pandemic. There must be a balance to find best practices to reduce emissions and one way is to make things and objects we engage with in our everyday life more smart and autonomous.