Employers in the US are grappling with whether and how to bring employees back to the office or other place of work. Using survey-based evidence, Jose Maria Barrero (Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México), Nick Bloom (Stanford/LSE) and Steven Davis (University of Chicago) find that four in ten Americans who currently work from home at least one day a week would seek another job if employers require a full return to business premises, and most workers would look favourably on a new job that offers the same pay with the option to work from home two or three days a week. High rates of quits and job openings in recent months appear to partly reflect a re-sorting of workers based on the scope for remote working.

Eighteen months after the pandemic began, employers are grappling with whether and how to bring employees back to the office or other place of work. They are taking a variety of approaches. Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan want bankers back in the office five days a week. Other firms, like Apple and Google, want employees onsite only part of the week. According to the Wall Street Journal, “Remote work is the new signing bonus” and “Workers have moved on” from restaurants and bars to jobs with higher pay and more flexible working arrangements. Anecdotal evidence suggests that desires for remote work are contributing to high quit rates and labour shortages in leisure, hospitality, and other parts of the economy.

To provide systematic evidence on these matters, we explore worker attitudes about returning to the office and the appeal of remote work in the June Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes (SWAA). We also draw on earlier waves of the SWAA – covering nearly 50,000 working-age Americans since May 2020 – to track the evolution of worker desires and employer plans for working from home in the post-pandemic economy.

In June, we put the following question to respondents who currently work from home at least one day per week:

How would you respond if your employer announced that all employees must return to the worksite 5+ days a week starting on 1 August 2021?

- I would comply and return to the worksite

- I would start looking for a job that lets me work from home at least one or two days a week, but return to the worksite if I don’t find one by August 1.

- I would quit my job on or before August 1, regardless of whether I got another job.

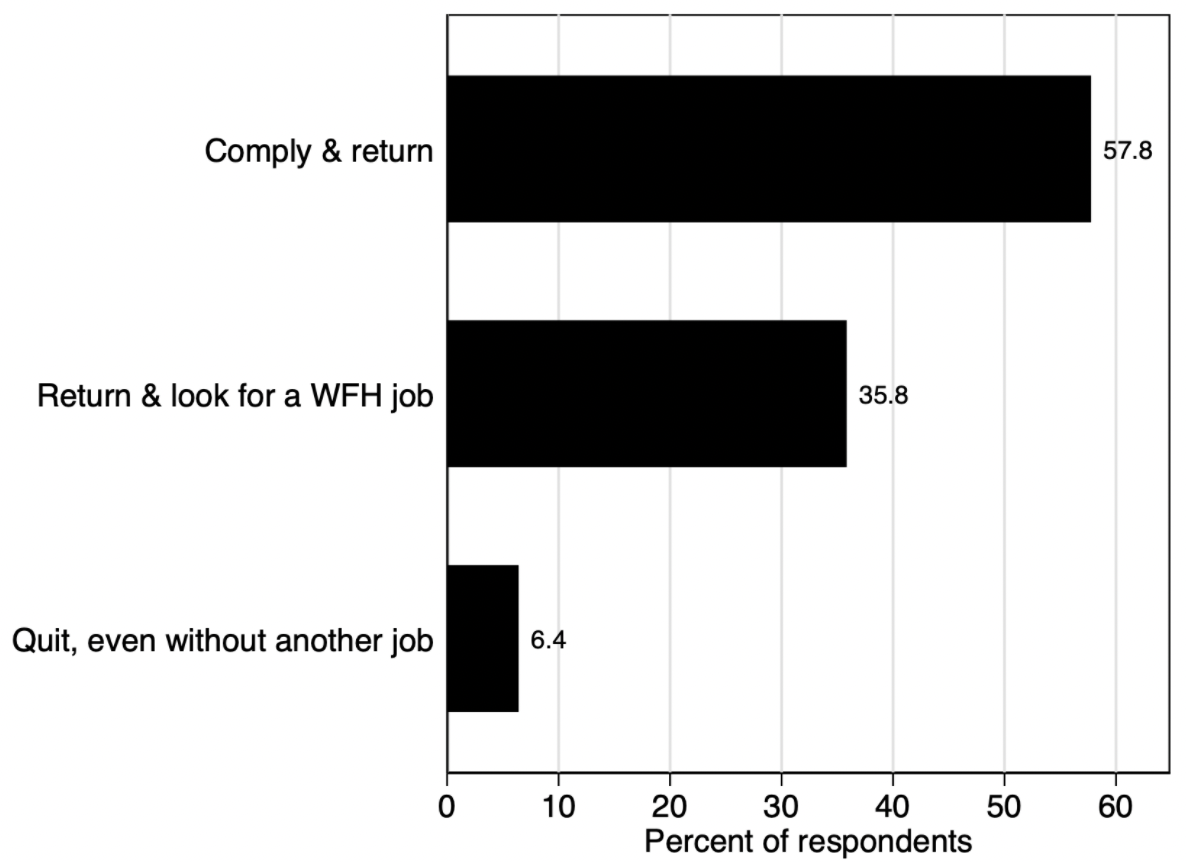

Figure 1: How would you respond if your employer announced that all employees must return to the worksite 5+ days a week starting on 1 August 2021?

Notes: Data are from the June 2021 Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes. We put the title question to survey participants who reported working from home one or more days in the survey week, were on temporary layoff awaiting recall, or were currently employed and paid but not working. 2,232 respondents met one of these criteria in a sample that contains 3,350 respondents who were employed or on temporary layoff in the survey week. We reweight raw responses to match population shares in the 2010 to 2019 CPS by {age x sex x education x earnings} cell.

Fifty-eight percent would comply with their employer’s directive and return full time to business premises. Thirty-six percent would comply but start looking for a job that allows some working from home, and 6% would quit rather than return to full-time in-person work on 1 August. For context, the latest numbers from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for May 2021 report a quit rate of 2.5%, which is the second highest rate since at least 2000. Figure 1 supports claims that high quit rates partly reflect the desire of many workers to continue working from home one or more days per week.

We also asked employed respondents in June about their receptivity to a new job that offers the option to work from home two to three days per week.

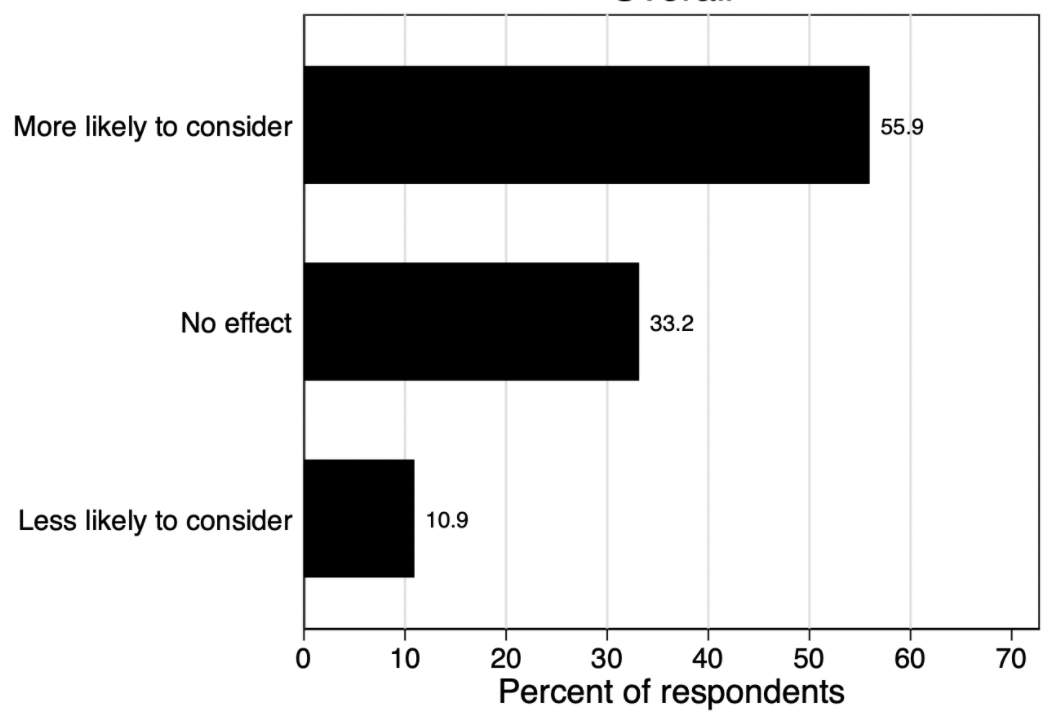

Figure 2: Suppose you got an offer for a new job with the same pay as your current job. Would you be more or less likely to take the new job if it let you work from home two to three days a week?

a) Overall

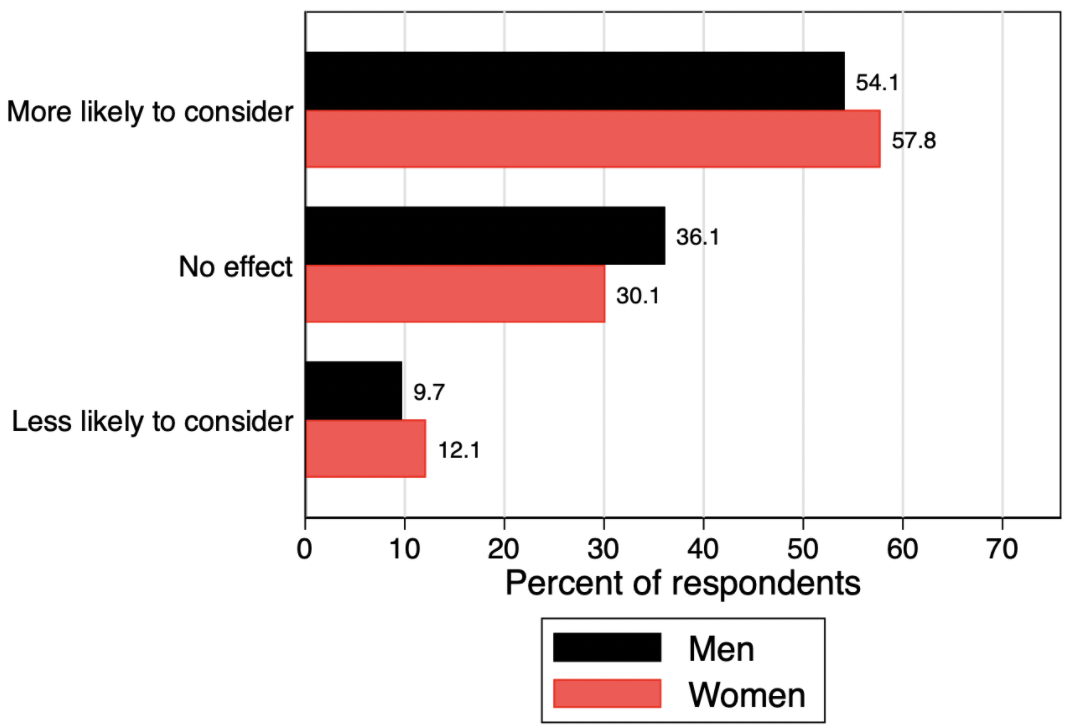

b) Men v women

c) Child status

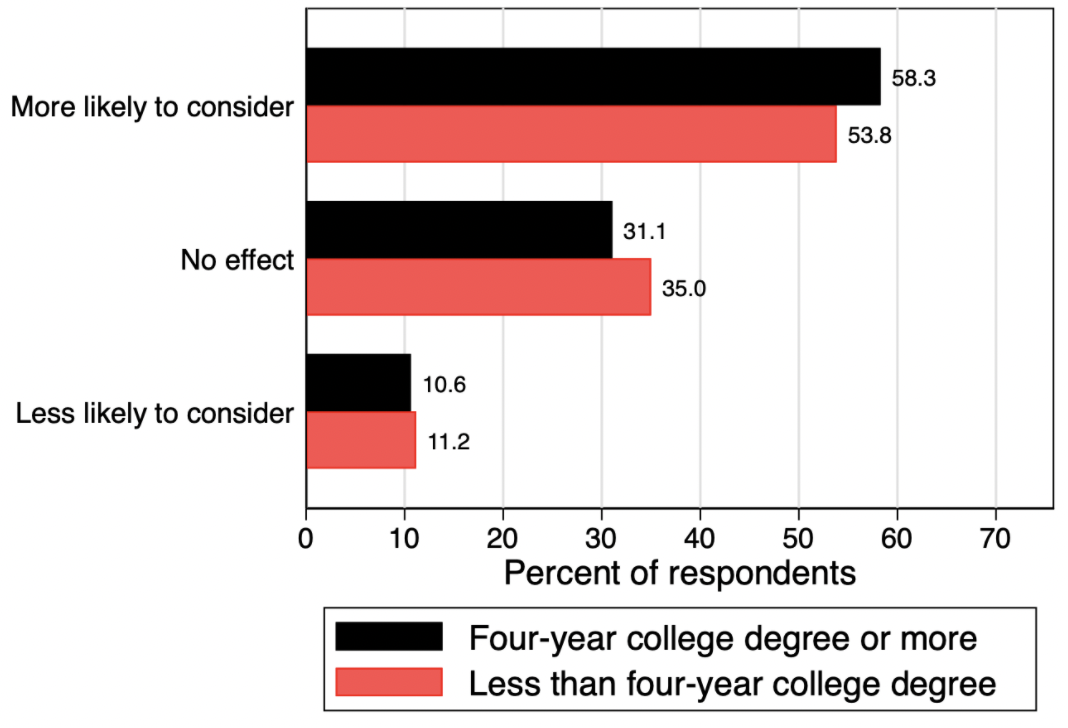

d) Education

Notes: Data are from the June 2021 Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes. Survey participants get the title question if they worked for pay in the survey week, or they were employed and paid but not working. We reweight raw responses to match population shares in the 2010 to 2019 CPS by {age x sex x education x earnings} cell.

As shown in Figure 2a, 56% of employees are more likely to consider a new job with a hybrid working arrangement. This proportion is slightly larger among women than men (Figure 2b) and among those with a four-year college degree. It is much larger, however, among respondents who live with children under 18 (64%) than among those who don’t (49%). Workers with children, thus, have the strongest preferences for hybrid working arrangements, presumably because it lets them more easily juggle work and childcare.

Many workers and employers have discovered that working from home works better than anticipated

Figures 1 and 2 say many employees prefer working from home at least part of the week, and they are willing to act on those preferences. But labour markets are two-sided. It’s not obvious whether and how fully employers will accommodate new-found employee desires to work from home. Media accounts suggest that many workers have the upper hand in recent months, and US labour markets look extremely tight by some measures. The JOLTS measure of the job openings rate is near historic highs.

Figure 3: Average days per week working from home after the pandemic ends

Notes: Data are from the May 2020 to June 2021 waves of the Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes, in which we ask the following type of question: “After COVID, in 2022 and later, how often would you like to have paid workdays at home?” In each survey month, we aggregate over the response categories to compute the average number of days per week that workers desire to work from home in the post-pandemic economy. We reweight the raw responses to match population shares in the 2010 to 2019 CPS by {age x sex x education x earnings} cell. We take the same approach for employer plans, using responses to “After COVID, in 2022 and later, how often is your employer planning for you to work full days at home?” The figure plots three-month centred moving averages of the monthly series, two-month averages at the sample endpoints.

Returning to the SWAA for systematic evidence, Figure 3 summarises the evolution of worker desires and employer plans for working from home after the pandemic ends. Both workers and employers have warmed to the idea of working from home since the onset of the pandemic. Throughout the period since May 2020, workers say they would like to continue working from home more than two days per week, on average, after the pandemic is over. In recent months, they say they would like to work from home almost half-time (2.4 days per week) in the post-pandemic economy. These statistics resonate with our findings in Figures 1 and 2 that many workers are willing to quit or seek a job with flexible working job before returning to full-time in-person work.

Employers plan for only about half as much working from home as workers want. As of June 2021, employers are telling their employees to plan for about 1.2 days per week of working from home in the post-pandemic economy. As Figure 3 shows, employer plans for the extent of working from home have risen 23% over the past year – from 1.0 days per week in July 2020 to 1.23 days in June 2021. Much of this upward drift took place during the first half of 2021, as the US economy reopened and labour markets tightened. While adverse selection concerns discouraged remote work before the pandemic, Figure 3 suggests much of the COVID-driven shift to working from home will persist long after the pandemic recedes. Moreover, these employer plans suggest firms are weighing the costs and benefits of working from home and settling on a middle ground.

Our results help in understanding the historically high level of quits and job openings experienced in the US economy in recent months. Labour market tightness, spatial mismatch, and skill mismatch may all contribute, but there’s another driving force as well. In particular, many workers and employers have discovered that working from home works better than anticipated. That’s led to new-found desires to continue working remotely after the pandemic ends. Some employers are willing and able to accommodate those desires, and some are not. As a result, many workers are re-sorting across employers and into jobs that better suit their preferences over working arrangements. As that process plays out, it will push up quit rates. It will also drive high job opening rates, as employers contend with the need for a higher-than-normal pace of replacement hires.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It first appeared at VOXeu.org in a slightly different form and is based on Why Working from Home Will Stick, a Centre for Economic Performance discussion paper, August 2021.

1 Comments