US workers have reportedly been switching to more attractive jobs since the pandemic. But labour market churn has remained fairly low in Germany, say Christof Röttger (IAB) and Enzo Weber (IAB and University of Regensburg).

The COVID crisis has been an extremely fast recession. Rapid declines during lockdowns were followed by steep recoveries. Industries affected by the restrictions suddenly had to ramp up business again when lockdown was lifted. For example, hospitality shed a lot of jobs during the crisis, and many firms report difficulties in filling new positions.

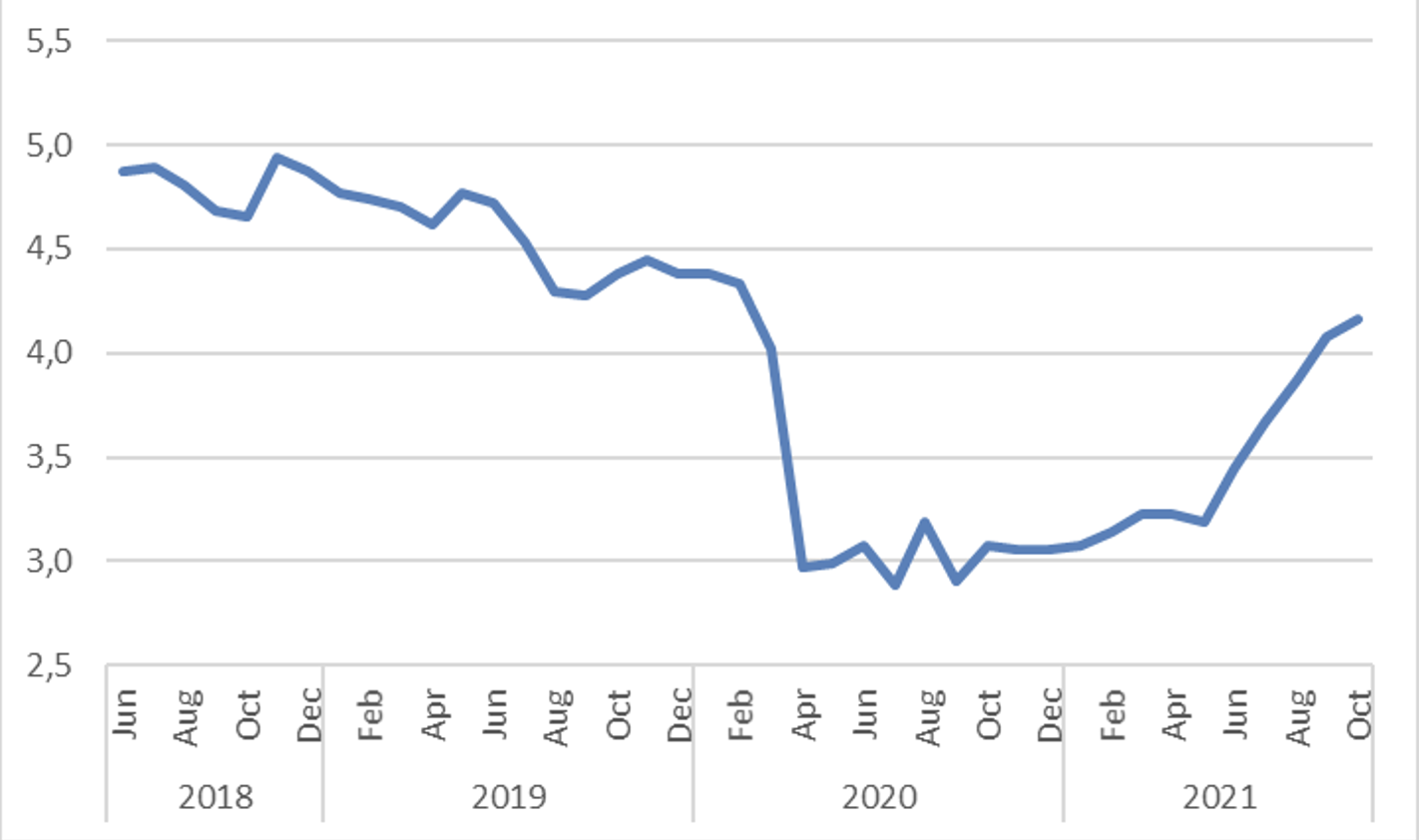

In Germany, the IAB’s labour shortage index shows that difficulties in filling vacancies have increased significantly recently. Hiring difficulties have almost returned to pre-crisis levels (on a scale of 0 to 10).

Figure 1: IAB Labour shortage index

Source: IAB

Where have workers made redundant during the crisis gone? Have they returned to the same industry? There is evidence that job applications moved from industries hit hard by the crisis to other industries. We analysed the question using data from the German Federal Employment Agency on employment and unemployment registrations. Specifically, we examined the extent to which people moved into new occupations after they became unemployed.

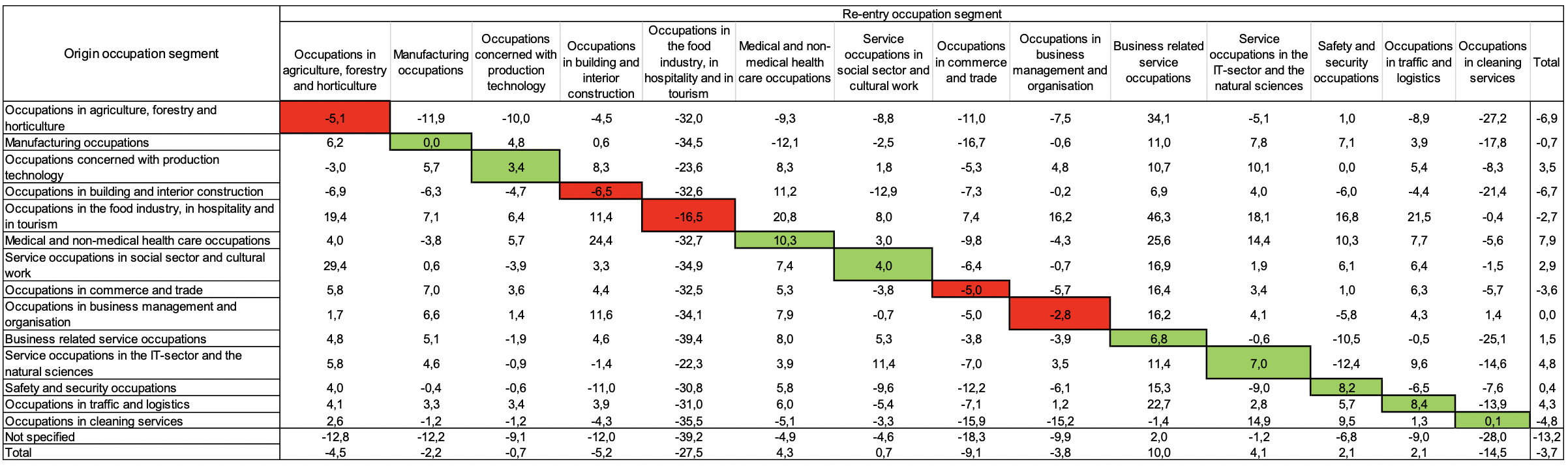

Table 1 shows the percentage change in unemployed people who were previously employed in a particular sector and who took up a job in a different one during the crisis period (Q2 2020 – Q1 2021) compared to the pre-crisis period (Q2 2019 – Q1 2020). For example, the number of people returning to jobs in the food industry, hospitality and tourism decreased by 16.5 per cent during the crisis.

Instead, these individuals increasingly moved into business-related service jobs, transport and logistics (e.g. delivery services), and health (e.g. testing centres), among others. Accordingly – and because more people were available – the number of unemployed people who had been working in the food industry, hospitality and tourism who returned to jobs at all also fell only slightly, by 2.7 per cent. The number of returnees also fell in some other sectors, such as commerce and trade, but at a comparatively moderate rate. Significantly more returnees were recorded in health jobs. In these, the number of unemployed people recruited also increased (last row in Table 1), as well as in IT and scientific and business-related service jobs.

When the unemployed got new jobs, they were slightly more likely to return to their previous occupation during the crisis period. The overall share of returnees was 55 per cent before the crisis and 56 per cent during it.

Table 1: Outflow of unemployed people with last job in occupation of origin, by occupational segment, Q2 2020 – Q1 2021 compared with Q2 2019 – Q1 2020, in per cent

Source: Federal Agency of Employment statistics, own calculations

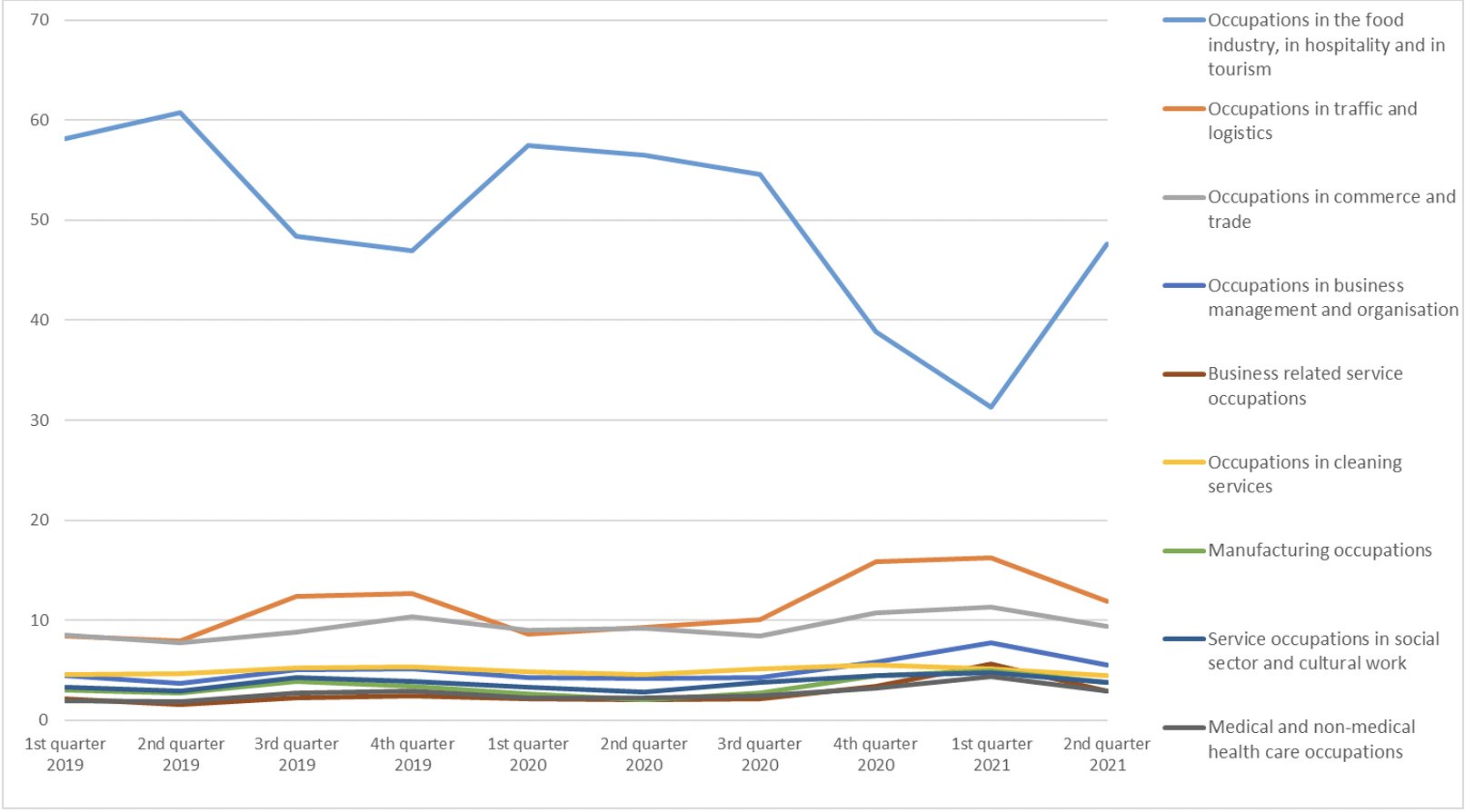

Figure 2 shows new hires by segment over time for unemployed people who had previously worked in the food industry, hospitality and tourism. Before COVID, about half of them returned to the same job segment after unemployment, and that did not change significantly in spring 2020. This is probably because Q2 2020 includes both the April lockdown month and a recovery of a month and a half. In the longer second lockdown, however, the share of returnees fell by more than 20 percentage points. Instead, more people moved into traffic and logistics, commerce and trade (e.g. supermarkets), jobs in business management and organisation, business-related service jobs, and health.

Figure 2: New hires of unemployed people who were last employed in food and hospitality jobs by occupational segment, in per cent

Source: Statistics of the Federal Agency of Employment, own calculations

In the case of jobs with few specific requirements, such as hospitality, occupational flexibility is particularly high. Bosses do not have to rely on a small pool of workers with suitable qualifications to fill vacancies, or the same people as before the crisis. Some post-COVID shortages are likely to return to normal over time. But looming labour shortages due to Germany’s ageing population mean raising potentials is essential.

On the one hand, long-term unemployment is still significantly higher than before the crisis – a result of the hiring weakness seen in many countries. In order to stop this persisting beyond COVID, individual wage cost subsidies could be temporarily extended in critical cases. In addition, especially in hospitality and other parts of the private sector, the number of mini-jobs (part-time jobs earning up to 450 euros per week, which are exempt from tax and social security) has fallen significantly. Here, it would be useful to introduce a social security bonus that supports the creation of full-time rather than mini-jobs in order to extend working hours. This would help the hotel and restaurant industry in particular to recruit staff. These measures will be all the more important if the fourth COVID wave leads to further restrictions. However, the strongest lever is migration. An open immigration policy, as well as efforts to limit the high level of emigration through improved (labour market) integration, are invaluable.

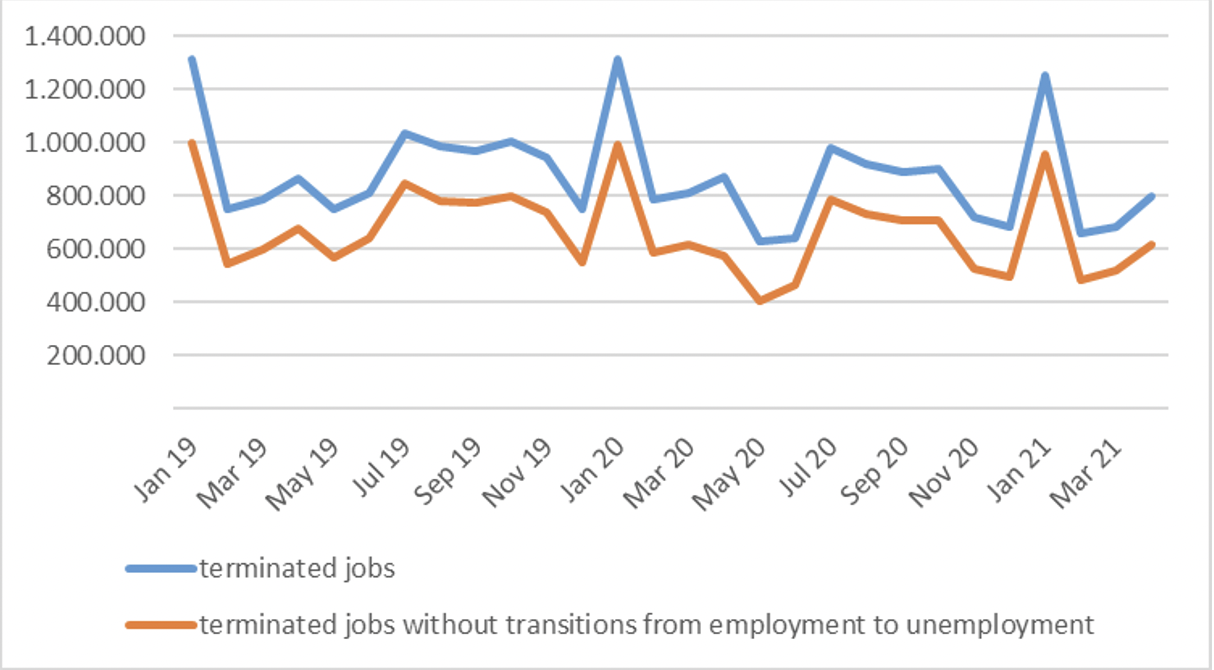

In the US, there are reports of employees leaving their jobs since COVID in favour of more convenient jobs. But this “big quit” has yet not been observed in Germany.

Figure 3: Terminated jobs (subject to social insurance contributions)

Source: Federal Employment Agency statistics, own calculations

It is likely that employees regard changing jobs in economically uncertain times as risky or less profitable, and therefore tend to behave conservatively. Search intensity in the labour market did not increase during the crisis. It can also be assumed that the extensive use of part-time furlough (Kurzarbeit) indicated a preference for keeping jobs and thus limited movement in the labour market. In any case, a substantial part of the COVID effect on the labour market was caused by fewer new jobs rather than more redundancies. As Table 1 shows, the number of new hires in in the food industry, hospitality and tourism is much lower than before the crisis. For sectors affected by the crisis, this means that a focus on bringing back workers who left is definitely not enough. All in all, the German labour market has not experienced a significant reshuffle due to COVID.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. They thank Katrin Schmidt and Marie-Luise Mohn for support.

2 Comments