The economic impact of COVID has hit young people, and especially poorer young people, harder than others. Andrew Eyles (Centre for Economic Performance, LSE) assesses the extent of the shock and what it means for social mobility, which was already in decline.

In the wake of COVID, labour markets around the world have experienced a sustained period of economic turmoil. Output has fallen, jobs have been lost, and, even for those lucky enough to retain their jobs, the very nature of work has changed. The UK has been no different in this respect. But there is room for optimism. The latest data show that the labour market continues to rebound from the nadir reached as 2020 drew to a close.

The immediate and pressing policy issue is weighing the need for further restrictions to quell the spread of new variants against the risk of hampering a robust economic recovery. Nonetheless, longer term thinking is as crucial now as ever. A vast economic literature has documented how job loss early in someone’s career can have persistent effects that accumulate over the course of their working life into substantial losses in earnings. Those left behind as the economy recovers are at risk of permanently lower earnings should they fall into repeated spells of unemployment, or have to settle for jobs that are a poor match for their skill set.

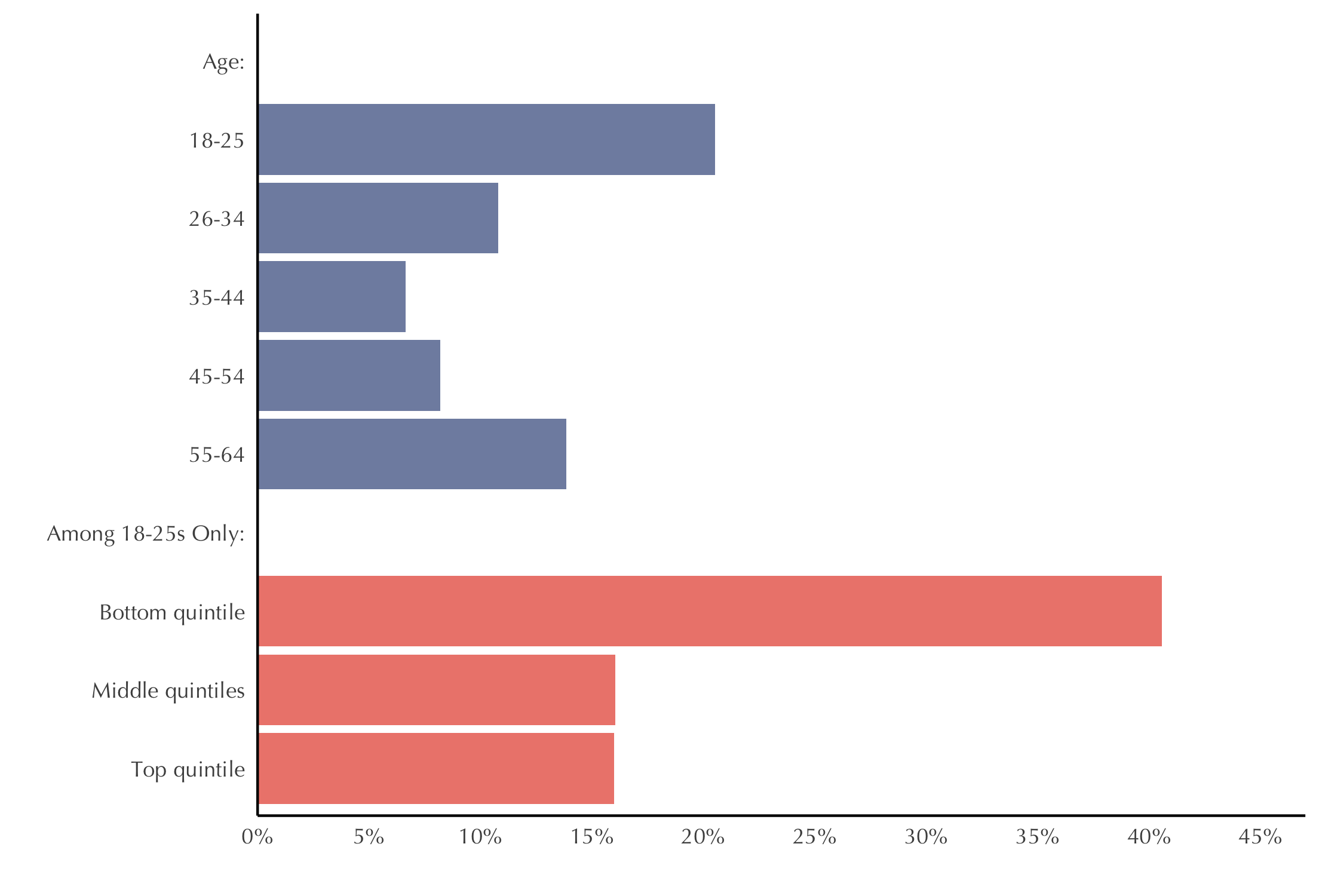

My recent research for the Economy 2030 inquiry highlights that this risk is more acute for some groups than for others. In particular, the young have been hard hit since March 2020. Of those aged 25 and under who reported having worked in January 2020, 16 percent reported being out of work a year later. This contrasts with just over 6% of workers aged over 25. Underlying this overall percentage is significant variation according to people’s circumstances prior to the pandemic. Young people who grew up in the poorest households are much more likely to have lost work since the pandemic began. Of those who grew up in the poorest 20 percent of households, 40 percent of those who had worked in January 2020 had become jobless between April 2020 and March 2021. This contrasts with 16 percent of those who grew up in the top 80 percent of the income distribution.

Figure 2: Young people from the poorest families were more than twice as likely as others to experience job loss in the pandemic

Proportion of respondents having recorded at least one transition into joblessness between January/February 2020 and March 2021, by age and family income quintile when growing up: age 18-to-64 (top panel), age 18-to-25 (bottom panel)

Notes: All estimates are for those aged 18-64 who reported being employed at baseline (January/ February 2020). Estimates are constructed using cross sectional survey weights also collected at baseline. Respondents aged under 25 are matched to the net household income quintile of their parents when the respondent was closest in age to 11.5. For joint matches, when respondents are matched at both age 11 and 12, the age 11 household income quintile is used.

Source: Analysis of Understanding Society COVID waves 1-8.

Understandably, the labour market fallout has had knock-on effects on other aspects of young people’s lives. Compared with pre-pandemic data, mental health among the young has deteriorated at a faster rate than that of their older counterparts. In line with the socioeconomic gradient in job loss, differences in financial security between those from more and less affluent family backgrounds have also widened.

While the choice of outcomes above (and the partitioning of outcomes by family background) may seem somewhat arbitrary, they are motivated by a common purpose – to draw out the social mobility implications of COVID. Social mobility can be measured in both relative and absolute terms. The former measures the strength of the relationship between one’s economic (or social class) origin and destination. The latter refers to whether someone’s ‘lot in life’ exceeds that of their parents.

The pandemic has the potential to affect both these measures. Declines in mental health among young workers can affect their future productivity and labour market participation. Financial distress can make it difficult for displaced workers to hold out for high-quality job matches. In each case, the earnings potential of young workers is depleted, making them less likely to reach the same level of prosperity as their parents’ generation. As these negative effects are most pronounced for those from less affluent backgrounds, both relative and absolute mobility may fall as a result of COVID.

The pandemic has struck against a backdrop of declining mobility in both absolute and relative terms. Even absolute upward mobility – once an iron-clad rule of life in the UK – appears to be under threat. Those who grew up under the shadow of the Great Recession now face a crisis of equal proportion at the onset of their careers. The potential for long-term economic scarring is substantial. An appropriate policy response, targeted at helping the most affected young workers, is key if COVID is to be a postscript, rather than a preface, to further declines in mobility.

The Economy 2030 inquiry is a collaboration between the Resolution Foundation (RF) and the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) at LSE. It aims to identify and respond to the economic challenges of the next decade. It is funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments