COVID brought about changes in the way people work, shop, socialise and travel. Patterns of crime and policing have changed too, as a report by Shubhangi Agrawal, Tom Kirchmaier and Carmen Villa-Llera (Centre for Economic Performance, LSE) highlights.

The pandemic and its associated lockdowns have affected crime levels both in the short and long term. In a new report for the Centre for Economic Performance, we show marked changes in the patterns of crime recorded by police. Acquisitive crimes such as burglary and shoplifting fell — and have remained low — but the level of violent offences, which had been rising for several years before the pandemic, has remained high. But there is substantial variation across crime categories and geographical areas.

Acquisitive crimes (robbery, shoplifting, burglary, and theft)

During lockdown, people worked from home and non-essential shops were shut. As a natural consequence, burglary and shoplifting rates fell sharply. Interestingly, though, even after the lifting of lockdown restrictions those crimes remained at lower levels. Figure 1 depicts how acquisitive crimes developed over time, and how much lower they are now when compared to the pre-pandemic period. Months in which crimes are below zero mean that crimes were below expected levels after considering (controlling for) seasonal characteristics.

Figure 1: Changes in acquisitive crimes (de-seasonalised, thousands), 2017-22

The graphs relate to local crimes — those which appear in the Police UK database, and which are attributed to a particular location. Our data does not allow us to assess the impact on cyber-crime and online fraud, but the recent Crime Survey for England and Wales suggests a large increase in those two categories of cyber-crime and online fraud since the beginning of the pandemic. This appears to suggest that there is a shift from local acquisitive crimes towards online offences.

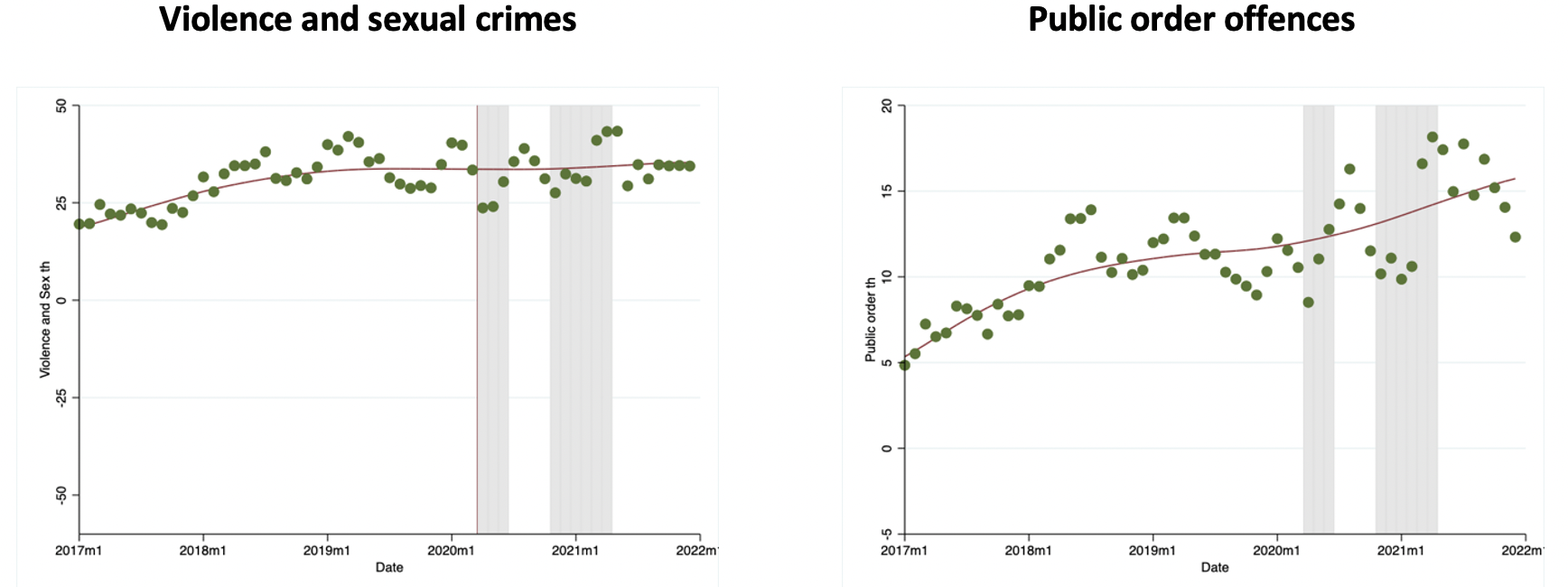

Figure 2: Violent and sexual offences / public order offences (de-seasonalised, thousands), 2017-22

Note: The plot shows monthly crimes in England and Wales as reported by Police UK after adjusting for monthly trends. We include only areas for which we have non-missing data since 2017.

However, the pandemic did not slow down violence. In fact, it has increased in the poorest areas of the country. Violence has been on the rise since 2014, and lockdown periods haven’t changed this. Lockdowns reduced overall crime rates, but violent crimes remain at high levels — and so make up a larger proportion of the crimes that police are now dealing with. Public order offences, which are crimes in which offenders cause public fear, alarm, or distress, were on the rise pre-pandemic, and the trend has since accelerated.

Spatial inequality

The pandemic has not decreased crimes uniformly, and disparities in crime outcomes correlate with economic indicators. To give an example, areas with a more secure labour market (measured by low claimant rates) have one fewer crime per 1,000 population in the violent offence categories than areas with high unemployment. The same is true for anti-social behaviour incidents. (Areas with a more secure labour market were also more resilient to the economic shock of the pandemic, and hence suffered much less economically from it.)

As a result, more than a third of the areas in the country recorded more crimes — and anti-social behaviour incidents — in 2021 than during the same period in 2019. Labour market indicators appear to be positive and significant predictors of higher crime in 2021 in all categories. Across all categories, areas with higher proportions of lone parent families, lower educational attainment, and a population with worse health on average are more likely to have more crimes in 2021 than in 2019.

Since crime rates tend to be higher in areas with high unemployment, policies to reduce unemployment would have a positive impact on reducing crime. The pandemic has highlighted increasing inequality in wages, education, and health. Crime is yet another area in which spatial differences are large, and resilient to events like pandemics.

This post is based on the CEP COVID-19 analysis COVID-19 and local crime rates in England and Wales – two years into the pandemic. It represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.