Pupils in India are back in classrooms, but teachers face enormous problems with discipline, attendance, concentration and loss of learning. Daya Sajeevan, Sreehari Ravindranath and Ravichandra Krishna (Dream a Dream) talked to teachers in Karnataka about their students’ behaviour post-lockdown.

“My students have become extremely aggressive and disrespectful. The other day I asked a student of mine to button up his shirt but he completely ignored me and opened up one more button right in front of me,” says Sindhu,* a high school English teacher from Bangalore, Karnataka.

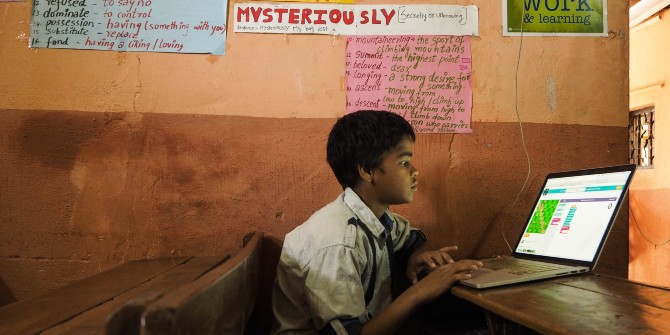

COVID has had enormous ramifications for schoolchildren in India. Many children and young people have had to deal with social isolation, the deaths of immediate family members and caregivers, and loss of family income. Cumulatively, these experiences have led to social, mental and emotional stress. Yet as schools have reopened after two years of closures, teachers are under renewed pressure to ‘cover the syllabus’ and ‘conduct unit tests.’ Dream A Dream conducted a qualitative study in February 2022 with 26 middle school and high school teachers from four low-income private schools in Bengaluru, Karnataka. The aim was to understand changes in student behaviour from the perspective of teachers. On average, respondents had over 12 years of teaching experience. Twenty of them were female and six male.

One unanimous concern among teachers was excessive aggressive behaviour among middle school and high school students, particularly boys. While outbursts of anger are commonplace in adolescents, after lockdowns the frequency and intensity of the outbursts have increased. Asked about the pre-pandemic situation, half the respondents said aggressive outbursts were a rare event among their students, 11 percent of them said they were a once-a-week occurrence, and 15 percent reported it used to happen twice a week. “Before the pandemic, I did not face a lot of behaviour issues in class. Only 2-3 percent of my students used to create issues and disturb others.”

But the post-lockdown situation is staggering: 76 percent of the teachers responded that aggressive outbursts happen every day in their classrooms, sometimes every two hours. “Before they used to listen to us, but now when we ask the simplest of things, they get provoked and start shouting at us.” ‘Students gang up to create nicknames for us and use foul language, which is very disturbing. Now we don’t use corporal punishment to discipline the students but we also don’t know how to handle this differently.” Other reported problems include bullying, physical fights, and verbal abuse.

Before the pandemic, most schoolchildren in India had lessons for at least seven hours a day, with each lasting about 30-45 minutes. The general expectation of the students during these classes was to be seated and pay attention to the teacher, which was rarely a challenge before the lockdown.

Students are now finding it difficult to sit still

“Now my middle school students ask for six or seven bathroom breaks in one class.” Having attended no physical or online classes — in some cases, for two years — students are now finding it difficult to sit still for 40 minutes. Their ability to concentrate and complete a task has also declined. “What took them only 10 minutes to complete before lockdown, is taking them 30 minutes now. To read one page takes them about 15 minutes,” says Janani,* a high school teacher.

Respondents also reported that students are unable to follow instructions or respond to factual questions during classes, which has become a challenge for teachers.

Students’ interest in learning activities, participation in group projects and day-to-day classroom activities have also declined. Teachers’ narratives reveal that the quality of work and punctuality in meeting deadlines are also affected. According to Rama,* a high school teacher, “My project was given a month ago, but so far only 20 percent of the students have submitted it. Even those who have submitted have not done a good job compared to the quality of work they used to produce before.”

Attendance has fallen considerably

Before lockdowns, students used to help keep their classrooms tidy by carrying out tasks such as fetching chalk and dusters from the staffroom, but teachers are now struggling to find volunteers for these roles.

Though students have started coming to school, attendance has fallen considerably. On a regular day, only about 40-50 percent of the students are present for classes.

Students have also forgotten their elementary knowledge of subjects, such as basic operations in mathematics. Reading and writing skills have also declined. The class averages in unit tests have also gone from around 60 to 40 percent in middle school, compared to lockdown. “My fifth grade students have forgotten [how] to write their names correctly and some of them do not remember their grades or subject names. We have to now provide revision for all basic subjects and it is going to take at least six months for the students to catch up,” says Meera,* a middle school teacher.

From having a handful of students who misbehave at times, to the majority of the class becoming increasingly aggressive, classroom behaviour management has become a challenge. While it is encouraging to see that teachers are not resorting to corporal punishment, it is clear that they are struggling without support and adequate training to handle these issues. Student-teacher relationships have also been severely strained and this demands urgent intervention.

Interventions must be are student-centred but also prioritise the wellbeing of teachers. The need to teach life skills, particularly emotional regulation and anger and stress management for both students and teachers, is urgent. It is also important to adjust lesson duration, the curriculum and pedagogy, as the majority of students are struggling to sit through lessons and pay attention. Placing students’ wellbeing above their academic performance by prioritising play and creating ways to de-stress is non-negotiable. Equally important is to provide teachers with training, support, resources and most importantly, showing that their wellbeing is integral to that of their students.

*Names changed to protect identities