Women’s magazines started to profile keyworkers during the pandemic. Shani Orgad (LSE) and Catherine Rottenberg (University of Nottingham) examine how these workers were depicted and the brief opportunity that the crisis afforded to call for ‘care justice’, rather than simply gratitude.

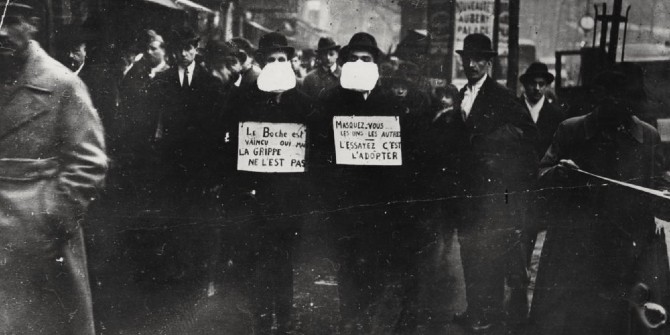

COVID has thrown society’s dependence on care and social reproduction into sharp relief. This labour, which is essential for society’s day-to-day functioning, has been historically perceived as women’s work and predominantly performed by women. During the first lockdown in the UK, when everyone one else was told to stay at home, the people carrying out crucial care and social reproductive labour were showered with public displays of gratitude. We saw this in the weekly ‘clap for carers,’ countless news stories, and the proliferation of homemade posters thanking ‘frontline heroes’ in public and private spaces across the country.

Female keyworkers were celebrated as heroes deserving public gratitude and appreciation

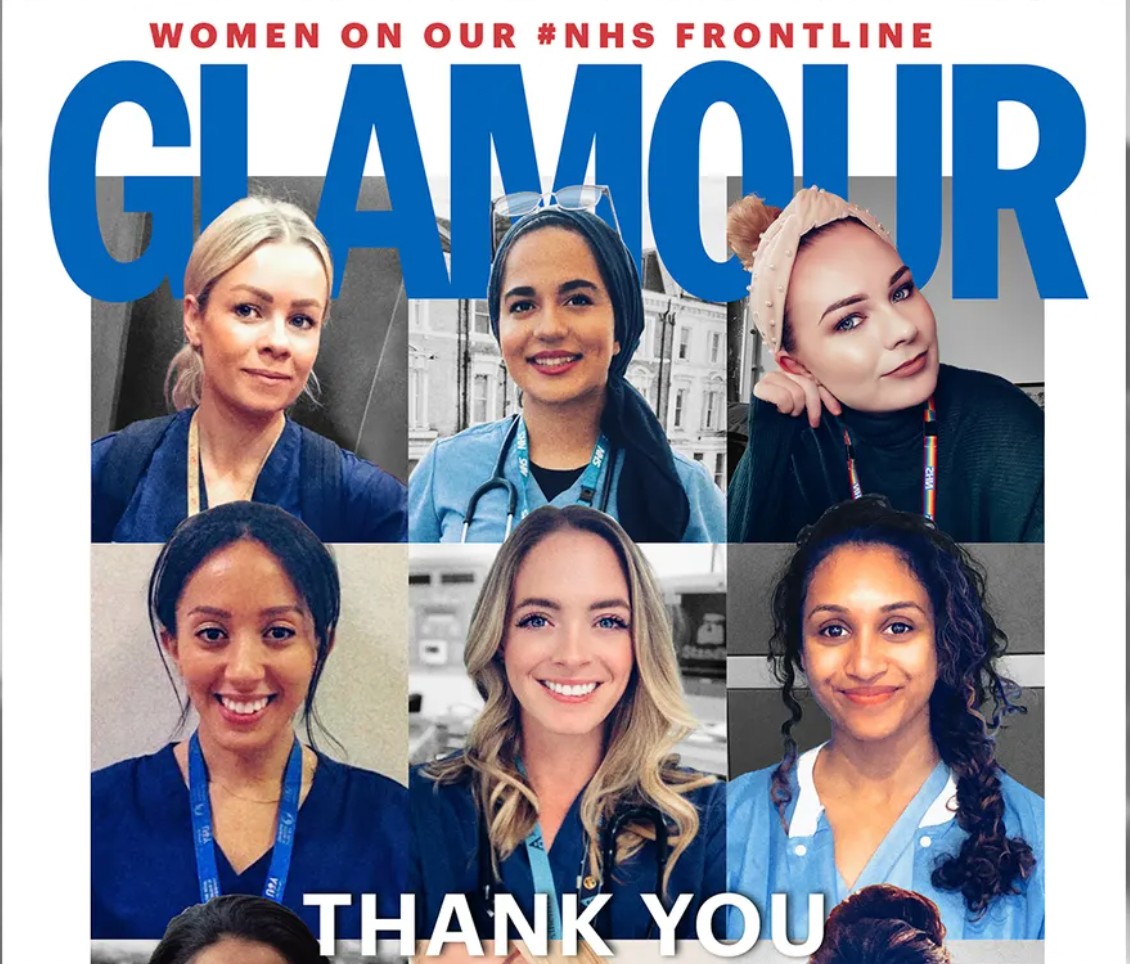

One of the surprising places where these keyworkers gained visibility and recognition was women’s magazines. In sharp contrast to the glamorous celebrities and high-powered middle-class women normally populating these magazines, during the first months of the pandemic these magazines gave significant space in their pages to profiles and images of keyworkers. For example, Vogue’s July 2020 special issue ran three covers featuring a train driver, a midwife and a supermarket assistant, while Glamour devoted two separate issues to keyworkers: one celebrating female NHS employees, and another highlighting the work of other keyworkers such as a gas engineer and a postwoman. Meanwhile, Harper’s Bazaar commissioned photographer Ian Rankin — best known for photographing celebrities like Kate Moss — to turn his lens onto twelve NHS workers.

Our analysis of representations of female keyworkers in UK women’s magazines during the pandemic — many of whom are working-class and women of colour — demonstrates how they were celebrated as heroes deserving public gratitude and appreciation.

Our study also reveals that these representations often focused on themes and aspects that we do not normally see in glossy magazines. In a striking departure from these magazines’ usual focus on individual and successful women, in the examples we examined there was a strong emphasis on community, collectivity and solidarity. Moreover, almost every woman whose story was featured in our sample confesses to feeling anxious and scared. These representations of keyworkers diverge from the typical ‘feel good’ tone of women’s magazines, which tend to sublimate anger and promote happiness and positivity. The stories also allowed some space for discussing structural issues and occasionally even for expressing demands for structural change, for example, in calls for government-subsidised affordable housing.

In this sense, we argue that women’s magazines gestured toward what Helen Wood and Beverly Skeggs call ‘care justice,’ which, as opposed to a sentimental ‘care gratitude,’ highlights injustice and makes concrete demands for substantive material change.

However, at the same time, even the messages of ‘care justice’ continued, in large part, to reinforce heteronormative femininity and the association of women with care. This was manifest in the persistent glorification of keyworkers who were mostly young, slim to average-sized, able-bodied, employed, resilient, positive, and caring. Moreover, while the stories often included accounts of keyworkers’ struggle, pain and anxiety, these nearly always appeared alongside expressions of gratitude, positivity and resilience — a move that transmutes negative feelings and critique.

This heightened attention to keyworkers has been temporary and has so far failed to translate into a longer-term ‘care justice’

Ultimately, then, our analysis suggests that women’s magazines have been a site that illuminates both the possibilities and the limitations of the recent media visibility of care work and those performing it. The heightened visibility of keyworkers in these magazines (and, perhaps, in the media more broadly) has indeed provided a space where the value of care and social reproductive work has been underscored and recalibrated, even as these representations have simultaneously reinforced heteronormative femininity, the stubborn association of women with caring, and the imperative to be resilient and positive. Crucially, this heightened attention to keyworkers has been temporary and has so far failed to translate into a longer-term ‘care justice,’ especially a concerted call to improve the dire working conditions of so many of these workers and the urgent need to invest in care infrastructure.

The post is based on Orgad, S. and Rottenberg, C. Media Visibility of Femininity and Care: UK Women Magazines’ Representations of Female “Keyworkers” During Covid-19. International Journal of Communication. May 2022. It reflects the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.