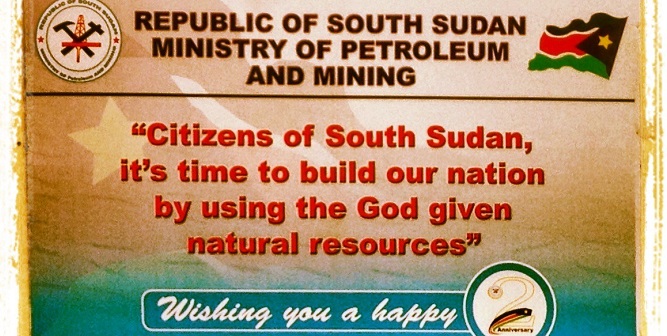

South Sudan is the world’s most oil dependent country, and yet it is projected to run out of oil reserves before 2030. Despite this looming approximate deadline, little, if any, petroleum revenue appears to have been invested in a future transition towards a non-oil economy. Instead, most of these funds have been widely reported as looted or otherwise mismanaged by the ruling government and people close to it.

However, recent global events are likely to have accelerated the government’s fiscal shortfall as world oil prices were in an historic decline even before the coronavirus pandemic led to today’s oil price collapse. There is now much less money for South Sudan to make from petrodollars as the country continues to head towards a new, potentially traumatic, decarbonised future. And while South Sudan is the recipient of large amounts of aid revenue, global humanitarian and development budgets are squeezed by the pandemic, which might further complicate the country’s economic, social and political horizons.

With these developments in mind, questions of how the Government of South Sudan will be financed are arguably more important now than they have been at any other time in the country’s nearly decade-long independence. But despite the ostensibly rising demand for non-oil revenue, very little is understood about the different financial sources that could potentially pay for government outside of the country’s nearly drained petroleum sector. Though there are concerns that the ruling elite will exploit other natural resources, including teak and minerals such as gold, thus far, these do not appear to be as readily accessible as oil.

‘Taxes for the People’ or ‘Forceful’ Taxes?

While the overarching tendency to focus on natural resource rents is understandable given the country’s recent history, it risks overlooking whether and how direct taxes could more meaningfully be used to finance the state. In fact, very little is known about the taxes that are collected in South Sudan by researchers and, as it turns out, by many South Sudanese too. This is despite persistent reports from the start of independence into the present, of multiple checkpoints and conflicts between the central government and states over taxation powers.

Given how little is understood about the country’s tax system, the research I lead within the Conflict Research Programme (CRP) seeks to better understand the various types of taxes in South Sudan and how taxes inform relations between people and the government. For the past few months, the CRP’s South Sudanese researchers have been conducting interviews with customary authorities, tax collectors, South Sudanese humanitarian and development workers, tea ladies and others across different parts of the country to better understand the types of taxes that people pay. In addition to mapping the variation in the types of taxes in the country, researchers also enquire into the social relations that taxes might inform through questions that touch on why people pay, and in some instances collect, taxes.

This blog highlights some of the range of taxes that people pay in the country and provides some insights into the ways in which the role of taxes and, to some extent, the role of government in South Sudanese peoples’ lives is heavily contested. One of the immediate findings is that even if taxes do not contribute to ‘official’ budgets there are numerous taxes in the country and that the distinction between different kinds of taxes is often blurry for taxpayers. For example, Mun (also known as muun/muun koc) is a type of informal tax, which is often not monetary, that is collected by some customary authorities in Dinka areas. And, as reported in Gogrial East, some distinctions between Mun and another type of informal tax known as Ajuer emerge:

‘When we talk of mun, it actually means that when the government asks local authorities including chiefs to collect cows as mun for the use of the government to solve some of the problems. But when we talk about Ajuer, it can mean small payments in terms of money or goods or services by the community. Ajuer in Dinka actually means voluntary acceptance to do specific task without the use of force. All this process is done by the Nhom gol or gol leader…’ [A gol is a Dinka byre or cattle camp though the term can also refer to groups that are defined by agnatic descent. And, the nhom gol is the father or master of the byre].

‘Well, sometimes two words can mean one thing in the Dinka language [Ajuer or Mun]. Like when I was young I used to hear people saying cows for mun which confuses me because the gol leader would collect the tax and give it to the subchief and the subchief will forward it to the executive chief and I didn’t even know where that chief finally gives the money to. This has been a big question in my head because I used to say to myself that I wished I [was grown] up so that I will be collecting taxes and use it to fulfil my needs. But now that I am grown, I am able to know where this money goes [and] mun actually refers to a physical asset like a cow or food but ajuer can be in any form’.

Adding to this complexity, another respondent also remarked that in Dinka, Ajuer roughly translates to ‘collections’, which is assessed at the end of every year whereas Ajuer hoot Nhiim translates to a ‘household tax’.

Other people provided additional descriptions of mun that highlight some capacity to bargain with different kinds of public authorities, including military officials, over taxes. This finding runs counter to the assumption that South Sudanese are entirely beholden to an elite kleptocracy:

‘On the issue of tax when it first started, we were paying sorghum and our energies through what was commonly referred to as “mun koc” – tax for the people. All these have been done and accomplished. The soldiers themselves have been taking cows by force in their grazing lands without questioning them, so typically the kind of tax system that we have been through since SPLA [Sudan People’s Liberation Army] days until today is what I called “forceful tax” so when the community felt that this is becoming stressful and the livestock were getting finished the community called for a meeting with the SPLA generals to discuss this issue in detail and the community raised to the commanders that if there is anything that the soldiers need, at least they should contact the community so that households contribute instead of soldiers taking by themselves. Even though this didn’t stop at once, it helped reduce the forced tax on the people’.

But even with this evidence for the capacity to ‘deal with’ tax collectors, to paraphrase the historian Cherry Leonardi’s work on how South Sudanese often relate to government, the same respondent added that:

‘…the question that we have never stopped asking [is] where does this money of ours go to? Because we have never seen anything tangible that has been done with the money that is collected from us. The problem comes here because we will never get an answer. The bogus answer that we get is that the money has been taken by the government and that this continues to keep us wondering, who is this government really? Because we are told it is the government that cannot give anything in return. This is truly our concern but if the government had been paying us back in terms of roads, I believe all of us will be willing to pay more taxes even twice a year’.

The push for increased public services in exchange for paying taxes is evident in other interviews, one of which put it even more bluntly:

‘It [tax payment] is just one-way traffic. We are the ones supporting the government, but the government is not doing the same thing for us’.

This touches on one of the most impactful research findings so far, whereby people feel that it is their duty to pay taxes, but are left in a state of confusion about whether and how these taxes contribute to improved public services:

‘As a citizen it is my duty to pay the taxes because I expect the government to provide the public services with that money. My taxes plus someone else’s taxes can make a difference in developing this country, but the fact is that there is no visibility in taxes we pay during these wars. There are big wars and we never know if our taxes are to be diverted to the funding of this crisis.’

Meanwhile, as South Sudan’s economic situation worsens, deeper fears about peoples’ capacity to pay taxes when it is so difficult to earn an income also emerge:

‘Currently I don’t know what the reaction of the community is, but I strongly believe that the community is not happy at all because imagine that there are people who spend months and months without seeing or even touching the notes of the money and now the government is saying that they must pay the money. Where will they get the money from?’

And finally, one of the sharpest findings highlights the perception that public officials are out for their own gain, even at local levels of government, rather than addressing public needs:

‘Since you are aware that the country is being drained by war, everything is just a struggle sometimes. […] [I]t is like every person [who] is given the opportunity to head a public office will think of his own benefit instead of that of the country. Definitely if the taxes that are collected don’t go to the right hands and the methods used to collect taxes are not trusted ones, how do we have a trustful relationship with the collecting authority?

As these interview excerpts reveal, studying South Sudan’s taxes vividly maps a ‘supply chain’ of social relations between people and government. It also speaks to some of the hopes, fears and disappointments that many South Sudanese reportedly feel about the role of the state in their lives and into South Sudanese citizenship as a whole.

Note: The CRP blogs gives the views of the author, not the position of the Conflict Research Programme, the London School of Economics and Political Science, or the UK Government.

Dr. Matthew Benson and his team had done a great research – informing and educative to young generation in South Sudan. ‘Ajuer’ has had been a common word in Dinka’s occupied areas in South Sudan especially Rumbek-Lakes State. People do not give only assets and services as ‘Ajuer’ but also ‘juar röt’ (voluntarily offer) themselves to go and fight for the libration of South Sudan. This research actually dig deeper to the grassroots meaning of taxes.