An “ethnic territory” may seem like self-explanatory unit: A bounded space inhabited by people belonging to the same ethnic community with shared interests and values. However, ethnic territories are thoroughly historical and contested constructions. While ethnic territories are historical and contested constructions, they are not innocent. Throughout history they have been deployed to naturalise and justify mass violence, exclusion, oppression, and inequality in many corners of the world (see e.g. here and here). During moments of violent upheaval and conflict, essentialised ideas of ethnic territories often come to the fore, informing people’s understanding of the conflict’s stakes and fault-lines. In such moments, people may start to think of conflicts in ethnic terms. Even when the origin and the stakes of a conflict have little to do with ethnicity, people may begin to think about it as a conflict between ethnic groups. By the same token, they may begin to attribute the cultural, or genetic, characteristics of their ethnic adversaries as causes of the war. For instance, a perceived ethnic adversary may be regarded as “violent”, “aggressive”, “greedy, “savage”, “rebellious”, “restless”, “backwards”, “undemocratic”, “cunning” and, hence, dangerous to one’s own ethnic community. In turn, this may lead to persecution, acts of violence, exclusion, or oppression of entire population groups. However, such ethnic stereotypes are not simply created on the spot by opportunistic leaders attempting to drum up support in pursuit of personal gain. Instead, they should be understood as identity categories lodged in historically constituted power structures, discourses, and, more broadly, in people’s ways of thinking and feeling.

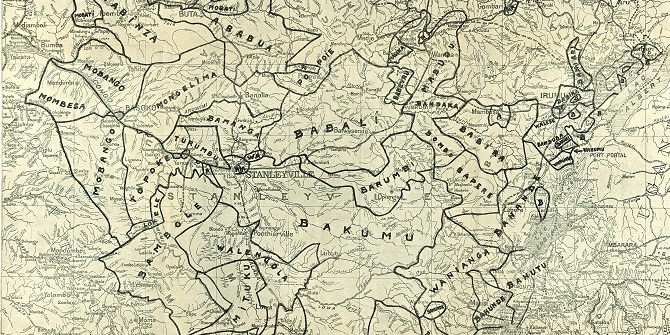

Because of the important role constructions of ethnic territories play in political struggles and persecutions it is paramount that researchers and others investigate and show how they are actually created and how they are used by participants in conflicts. This is both to destabilise their apparent self-evident nature and to show how they are harnessed to do political work. In a recent article, I dissect how ethnic territories have been historically constructed, imagined and used in political struggles for power and resources in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo). The study focuses on the area directly west of Lake Kivu, known as Kalehe Territory, which has been severely affected by violent conflict for more than two decades. The main argument of the article is that the constructions of ethnic territories that are used by actors in struggles over political space in the Congo are conditioned by what I call ethnogovernmentality. I show that while ethnogovernmentality was introduced and institutionalised during the colonial period, it has nevertheless shaped post-independence politics in eastern Congo in important ways, including the violent conflicts of the last two decades.

Ethnicity, territory and conflict in eastern Congo

The nexus between ethnicity and territory is highly contentious and formative of political struggles in eastern DR Congo. It is at the crux of its violent conflicts as issues related to ethnicity and territory intertwine with fundamental issues of citizenship rights, and authority over territory, populations, and resources.1

For Foucault, governmentality concerns the supplementing of older forms of disciplinary and sovereign power with scientific, calculative, and liberal ways of governing populations at a distance, which he termed bio-politics. The aim of governmentality was to secure the welfare of the population, improve their condition, and augment their wealth, health and longevity. In postcolonial contexts, like DR Congo, the continuing salience of ethnicity and territory must be understood in the context of longer histories of colonial rule and struggle. Colonial ethnogovernmentality was a particular form of governmentality. In brief, it denotes a heterogeneous ensemble of biopolitical, and territorial rationalities and practices of power concerned with the government and creation of indigenous territories. Through ethnogovernmentality colonial authorities attempted to impose ordered visions of territory and race upon ambivalent places and cultures. The creation of colonial ethnic territories served multiple, often contradictory objectives. One the one hand, colonial officials sought to make colonies profitable and generate revenue to support the costs of administration; on the other hand, they were charged with enforcing order and stability, and caring for the well-being and “progress” of the colonised population. To such ends a multitude of biopolitical practices were deployed such as censuses, ethnography, taxation, internment, control of population movement, infrastructural projects, health measures, map-making, and demographics, which had various territorialising effects. Through the making of “ethnic territories” colonial regimes sought to balance demands for profit and self-financing with objectives of indirect rule, maintaining order, managing dispossession, and upholding racial boundaries and hierarchies. A key component of colonial ethnogovernmentality in the Congo, and elsewhere in Africa, was the creation of chefferies (chiefdoms).

Chiefdoms were envisioned as mutually exclusive ethnically discrete territories ruled by a single customary chief governing through customary law. Through the creation of chiefdoms the colonial authorities aimed to govern indigenous people at a distance as “tribes” or “races”, in their natural environment, and through their own customs and political institutions. Through this territorialisation of ethnicity, hundreds of chiefdoms were created in the Congo. They were objectified and rendered legible and governable as a “vital environment” of socio-natural processes. The objective of this rationality of government, known as administration indirecte (indirect rule), was to ensure that order could be maintained at the same time as the indigenous populations were turned into productive and taxable subjects. The figure of the chef coutumier (customary chief), became particularly important in colonial administration indirecte. In colonial discourse he was framed as the embodiment of traditional indigenous political institutions, and, in particular, as a father-like monarch, despite the enormous diversity in indigenous political cultures. As such customary chiefs were regarded as “a very useful class, interested in maintaining an order of things” and granted extensive powers over their “ethnic” subjects.

However, the indigenous political units were not the pliable natural units imagined by the colonisers, but rather complex polities populated by people with diverging interests and complex external relations. As it were, across the territory, the colonisers were faced with many forms of resistance including evasion and rebellions. This was also the case in the eastern part of the colonial territory. Here, local leaders, such as the Bashi chief Kabare and the Banyungu prince Njiko, mounted rebellions against the colonial authorities. As a result, violent repression became a constant companion to biopolitics. Often, the tactics deployed to establish colonial rule were subject to considerable contention among state cadres. While officials in Brussels insisted on the extension of territorial administration and indirect rule, to facilitate a more peaceful colonisation, personnel on the ground argued that violence was a necessary evil to subdue indigenous people that tried to resist colonial rule. Therefore, ethnogovernmentality fragmented into multiple fields of struggle in which various indigenous and colonial actors were engaged. As a result, the creation of ethnic territories became a dynamic process where boundaries were determined by political struggles, in which violence and the threat thereof played a constitutive role.

At the same time, theories of racial superiority of mixed biblical and scientific vintage were harnessed to authorise colonial decisions to create ethnic territories. This demonstrates that the scientific foundation of ethnogovernmentality was itself irredeemably racialised, arbitrary, and intrinsically political. In this regard, the ethnographic knowledge which was used in ethnogovernmentality can be described as a form of “epistemic violence”. In the article I detail how ethnogovernmentality played out on the ground in the area west of Lake Kivu during the colonial period. I show that the creation of chiefdoms was a dynamic process in which royal indigenous elites and colonial authorities collaborated to establish colonial and chiefly authority. The article focuses on the creation of Buhavu chiefdom, which was created in the 1920s, and which merged several hitherto independent indigenous polities and culturally diverse populations into a single chiefdom under the rule of the Bahavu chief.

However, several indigenous leaders and groups refused to recognise colonial overrule, including rival Bahavu chiefs, and chiefs of the people collectively known as the Batembo. The Batembo lived in small independent communities on the eastern edge of the Congo River Basin. In the Batembo polities authority was dispersed among several clans and groups and as such the idea of a mono-ethnic territory ruled by a single chief was significantly at odds with the existing political culture. Only through severe repression, were these communities and their leaders forced into submission. In this regard the creation of the Bahavu chiefdom was “a violent act of exclusion and inclusion”. Its creation violated the area’s existing cultural diversity and political institutions, silenced subaltern and rebellious voices, and concentrated authority in the hands of indigenous royal élites who were willing to collaborate with the colonial authorities.

Ethnogovernmentality in the postcolonial period

I also show that even though ethnogovernmentality largely failed to produce the desired effects, it did transform the existing political order in the area such that European discourses of ethnicity, territory and authority, became more salient. This is quite clear from the politics that emerged in the terminal colonial period and in the immediate post-independence period. Independence created opportunities for a new set of Congolese actors to participate in politics, including in Buhavu chiefdom. Here a group of leaders, claiming to represent the Batembo ethnic group, demanded the right to territorial self-rule. Their demand for a Batembo territory was cast within the parameters of ethnogovernmentality insofar as it was justified on the ground that it was an economically sustainable and culturally homogeneous bounded space, and which as such deserved to be recognised by the government as a self-governing entity. This points to the limits of decolonisation through claims to contiguous ethnic territories.

During the Congo Wars the struggle to create a Batembo territory became engulfed in the larger dynamics of regional war. Batembo leaders mobilised a powerful militia, which, with support from the Congolese government, fought Rwandan army units and their Congolese allies. However, they also had an ambition to convert their newfound military strength into political power, and especially to use it to push for the creation of their own ethnic territory called Bunyakiri. However, post-war politics did not play out in their favour, and, like many other Mai-Mai groups, they were side-lined and outmanoeuvred once they entered the arena of national politics. Today, Batembo leaders still clamour for the creation of an independent Batembo chiefdom. Moreover, armed groups are still active in Batembo areas, and as during the wars they legitimate their presence and rule by claiming that Bunyakiri is governed, infiltrated and threatened by ethnic foreigners. As such, they harness the idea of a homogenous ethnic territory in their political quests to rule territory, populations and resources. In this regard, even though the dynamics of militarisation and armed group mobilisation in eastern Congo have distinct logics, these logics also interact with conflicts over ethnicity, territory, and authority in complex ways.

1 See the following articles: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691102801/when-victims-become-killers and https://www.jstor.org/stable/4392875

Note: The CRP blogs gives the views of the author, not the position of the Conflict Research Programme, the London School of Economics and Political Science, nor the UK Government.

I read your article about ethnogernementality. It is useful in understanding the plight of minority ethnic groups and their quest for territory and representation. I gather that batembo are scaterred among various territories like kalehe kabare walikale and even shabunda. I need iformation regarding their total number, and if possible the number that living in the territories of Kabare and Kalehe. It is for research purpose